La Foce: Legacy of love

A young heiress’s vision turned a forlorn corner of Tuscany into something like Arcadia. Today the next generations keep her spirit beautifully alive.

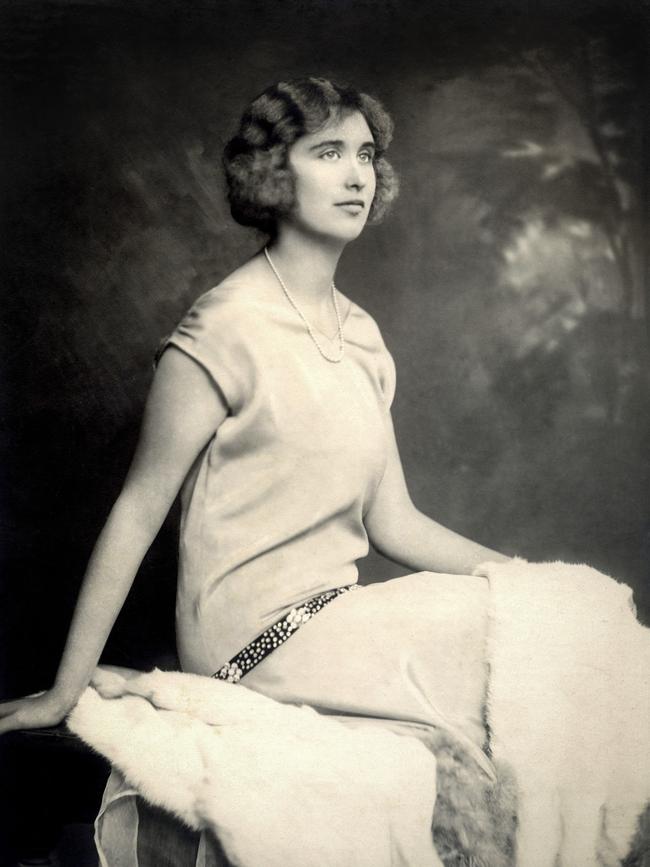

On a windy, steel-skied October afternoon in 1923, Iris Origo – the 21-year-old British-American heiress who in 1947 would publish War in Val d’Orcia: An Italian War Diary, 1943-44, one of Italy’s most compelling 20th-century memoirs – laid eyes for the first time on the valley after which her famous book was named. Years later, when she was in her late sixties, she recalled that arrival: “The road was nothing more than a rough cart track up which we thought no car had surely even been before. Long ridges of low, bare clay hills … ran down towards the valley, dividing the landscape into a number of steep, dried-up little water-sheds. Treeless and shrubless but for some tufts of broom, these corrugated ridges formed a lunar landscape, pale and inhuman; on that autumn evening, it had the bleakness of the desert, and its fascination.”

At the time, she and her then-fiancé, the marchese Antonio Origo, were in search of an estate to call their own, far from Florence (where she had been raised by her Anglo-Irish aristocrat mother at the Villa Medici) and from their rarefied social circles. The Origos shared a sense of noblesse oblige – an unusually keen one, for their European class – and they knew what they were looking for: “A place with enough work to fill our lifetime,” Iris wrote, but one that she hoped “might be in a setting of some beauty.”

La Foce, as the property on that lonely summit in Southern Tuscany was called, seemed ripe with the promise of the former: the original villa, built in the 15th century as an inn, had no electricity; there was perilously little water. Across the land, topsoil had been denuded by poor management. There was neither school nor infirmary to service the more than 25 tenant farmers and their families who worked the fields. But the place captured the Origos’ imagination; they purchased its 3500-plus acres – scrub-oak forest, poor grasses, vast tracts of unyielding stony clay – and set about creating a world of their own, one that would take decades to realise.

Today, if you follow the route the Origos did almost 100 years ago – southwest from the spa town of Chianciano Terme, along narrow highway 40 (also known as the strada vecchia senese; still bumpy, albeit paved these days) – you will weave and wind and climb, and at a certain point you will reach that same summit, the whole of the Val d’Orcia opening out before you. The tower of Radicofani to the south; the monolith of Monte Amiata, dominating the horizon to the west; tilled earth and alfalfa fields and vineyards stretching in an agrarian patchwork for miles in between. But as for La Foce itself, long gone are the corrugated ridges and bleak stretches of scrub, and the listing, near-decrepit buildings. In their place is something like Arcadia: a sedate three-story villa, its walls painted a rich yellow-gold, its front entrance shaded by two holm oaks and its terraces awash in wisteria; cypress lanes and lush woods; and surrounding the house for several acres, extensive gardens that are among the most famous in Italy, impeccably maintained, descending in terraces down the eastern slopes of the valley.

La Foce’s is a story of perseverance and imagination in many senses. Throughout the 1920s and ’30s, the Origos comprehensively rehabilitated the estate, introducing innovative farming and irrigation technology and equipment, building medical and social facilities, creating a nationally accredited school for the local children, and providing literacy and health courses for the adults. Its thousands of acres, grown from the original 3500 to more than 7200, morphed from an impoverished, near- medieval landscape – “as bare and colourless as elephant’s backs”, in Iris’s lyrical description – into a thriving model of modern, self-sustaining agriculture.

But it was World War II that put La Foce at the centre of Italian history. In late 1943, Germans forces occupied Tuscany; by 1944, Americans were pushing up from southern Italy and Scots Guards were descending from the north, and the Origos found themselves and their estate at the war’s chaotic crossroads. At significant personal risk, they harboured partisans, orphans, and Jewish refugees escaping certain deportation to camps, and helped British POWs escape – a harrowing period, described compellingly in Iris’s diaries. The orphans, evacuated from Turin and Genoa, were secreted in cellars, the prisoners and partisans in storage rooms or tenant farmhouses. In one remarkable instance, Antonio Origo held German soldiers at bay with a rambling disquisition in their own language while at the other end of the property their “guests” disappeared into the relative safety of the forest. When in June 1944 the estate was requisitioned by the Wehrmacht and the Origos were forced to evacuate, they walked their own daughters, along with more than two dozen orphans, across the mine-studded landscape to Montepulciano – eight miles away.

Wandering the neat parterres of La Foce’s garden today, the background track one of birdsong and the industrious hum of bees, it’s almost impossible to imagine the ground rumbling with passing Nazi tanks, or the still air rent by the hiss and shriek of American Beechcraft bombers. For the contemporary visitor, Iris Origo’s felt legacy is this house, this garden: the fruits of her tireless cultivation of beauty and refinement, in a place that had offered next to nothing of either, for decades. To achieve it, she enlisted the British garden designer and architect Cecil Pinsent, a friend of her mother who had established his reputation designing various well-known villas around Florence (including Bernard Berenson’s famous gardens at I Tatti in Fiesole). Between 1925 and 1939, La Foce’s formal Italian gardens grew up around the villa, imagined in a series of “rooms” delineated by the neat hedges and potted lemon trees, which come out of the limonaia in spring and summer. A simple travertine stair leads up to a terrace of roses and peonies, a long wood pergola that runs along it woven through with century-old wisteria vines, their gnarled roots kissed by borders of tulips. Below, a larger, double staircase leads to the garden’s most recognisable view – a trapezoid of immaculate green lawn, punctuated by more hedges, bookended by a classical grotto and an elegant stone pool. At the far western end is a sentinel line of cypresses and, beyond them, the unforgettable view of Monte Amiata.

Iris Origo died in 1988, but some 2200 acres of the property remain in the hands of her two daughters, Benedetta and Donata Origo, and Benedetta’s own daughter, Katia Lysy. Together these second- and third-generation Origo women have kept La Foce relevant.

The villa itself, its interior completely renovated in 2018, can be taken over for events and holiday lets. Likewise the handful of farmhouses, restored over the past two years, that are scattered across the estate. The garden is open to the public by appointment a couple of days a week; private guided tours, given by staff, are also available. A couple of hundred metres further down the vecchia senese is the Dopolavoro, a social centre that was built for the tenant farmers and contadini by the Origos in 1939 (it translates literally as “after work”). This has been transformed by Katia and local food-hospitality guru Asia Chirdo into a modern restaurant; with a cool, vaguely industrial design scheme, a huge open grill, a large back garden, and a canny wine list featuring überlocal producers (La Foce is handily within easy striking distance of both Montalcino and Montepulciano), it has become a Val d’Orcia address in its own right. And every summer the estate hosts an annual classical music festival, Incontri di Terra di Siena, founded and curated by Benedetta and her son Antonio Lysy, an accomplished cellist.

That such an unyielding setting begat such an idyllic place is in large part thanks to the largesse of Iris Origo’s aunt, Justine Cutting Ward, who like Origo’s father, William Bayard Cutting, came from one of the great 19th-century New York families. “Of all this immense family, and its immense wealth, none of the four siblings of that generation of Cuttings had children except for my great-grandfather; Iris was his only daughter,” Katia told me, when I came to stay with her and her mother at the villa for a long weekend in May. “So this American aunt came here to visit, and was shown into a bathroom with very little running water, on this rather bleak, to her eyes, estate – and many of the family did apparently think, ‘What is she doing there? This is madness.’

“But knowing that my grandmother had this vision, and this desire, but couldn’t justify using the little water there was for it, this aunt paid for a pipeline to be put in, leading from a lake up in the woods – a lake that was quite far away – which would bring in enough water for a very large garden. And that’s how my grandmother could begin to realise everything here.”

Lysy and I are sitting in canvas campaign chairs on a lawn at the back of the villa – a sort of antechamber to the first of the garden terraces. Overnight rains have rinsed the air of all haze, and everything green glows a bit more than usual, as if lit from within. It’s peak wisteria season; the pergola on the terrace above us is one long, dense froth of bright purple. Wet soil and roses scent the breeze. In the distance, fugitive sunlight spills between scuttling clouds, painting the eastern face of Monte Amiata blue, silver, blue, silver.

The afternoon before, Lysy had taken me to see La Foce’s farmhouses, the recent renovations of which she had overseen. Each of them is unique in décor and in character, filled with brocante, framed botanical prints and paintings, antique iron and wood beds, and invitingly overstuffed sofas and chairs. Montauto, which sits above and behind the villa, down its own strada bianca, is the largest and probably the most conventionally luxurious of them; Lysy tells me her mother lived there for several years before moving back into her apartments adjacent to the villa. Its sunny, newly renovated open kitchen is a shelter-magazine dream, the cabinetry painted Tiffany blue and the island clad in ornate tilework. In a cosy downstairs bedroom, a headboard is still covered in its original 1940s print – a charming repeat of hunting dogs in a wooded landscape, chosen by Iris Origo. Upstairs are a large living room and more bedrooms. There are several patios, with the requisite profusions of wisteria, and a pool set in a lawn overlooking a meadow full of wildflowers.

Further up the hill, next to a small castle that once belonged to the estate, are Belvedere Piccolo and Belvedere Grande – attached properties, with a more pared-back, sunny décor and a magical shared gated garden. And nestled on a slope below the villa is Fontalgozzo; though a bit smaller than Montauto, for my money it wins the day, with its expanse of sun-saturated lawn tumbling down towards the valley, its gorgeous keyhole pool, its freestanding dependence with bedroom and bathroom (ideal for a privacy-craving teen or couple), and the indelible beauty of its Val d’Orcia views.

For those in it to splurge, however, the villa itself – known formally as Villa Origo – is the thing. It sleeps 26 people comfortably across a dozen-odd bedrooms, all ensuite, including a dreamy master with its own sitting room and a huge changing room, detailed in its own, delicate shade of blue. There are the wide terrace and lawns, or the cool shade of the limonaia, for summer lunches and suppers; and the cosiness of the ground-floor sitting-dining room (with its own grand piano) and the panelled library, complete with fireplace and thousands of volumes lining the shelves, when autumn evenings arrive. The spectacular double-height formal dining room has a glass ceiling casting a lozenge of sunlight down onto a long glowing walnut table, and ornate frescoes commissioned by Pinsent; its mezzanine harbours secret doors that lead off to second-story corridors. On a wall that abuts the curving main staircase, there is an enormous mural of the estate, the crete – the Val d’Orcia’s famous clay-ridge hills – undulating down in sinuous hand-painted ribbons.

Villa Origo is beautiful but accessible; unfailingly, but never forbiddingly, elegant. Though excellent taste is on display everywhere, there’s no surface or textile, no piece of furniture or book that says Do Not Touch. Above all, it is, like the rest of the estate, a thoughtful response to the place in which it sits – one that, even minus its extraordinary history, is an exceptionally inviting one in which to spend a day, or a week.

But that history matters. The singular atmosphere of sanctuary derives as much from knowing La Foce’s own origin story, knowing the events that played out here, as it does from the pleasures of the garden, or perusing the library shelves, or walking the winding road down to the Dopolavoro at dusk. At La Foce, the past is alive in the present, waiting to speak; which seems much the way Iris Origo would have wanted it.

–

Lafoce.com. Farmhouses, from €3800 a week; Villa Origo from €26,000 for three nights.

For more of Iris Origo’s story, read War in Val d’Orcia: An Italian War Diary, 1943-1944; A Chill in the Air: An Italian War Diary, 1939-40; and Images and Shadows: Part of a Life, published by Pushkin Press

Read more in WISH Magazine’s Italian Issue, out Friday