How the Big Five are returning to South Africa’s ‘Serengeti’

In an arid corner of the Eastern Cape, an ambitious project is putting the region’s iconic wildlife back where it belongs.

In the Great Karoo, life and death are separated by a mere whisker, a whisper, a plaintive last breath. In the shadow of the Sneeuberge (Snow Mountains), a cheetah is dropping low and tensing for the hunt. Burchell’s zebras loop snout-to-tail in a streaky procession; the springboks are stiff with adrenaline. Samara Karoo Reserve tracker AJ Murphy dips his telemeter towards the unfolding story; he’s registered a signal from the cheetah’s collar. Though but a murmur, it’s an alarm more potent than animal instinct.

We don’t witness the attack. The cheetah’s movement is lost in the blur of grasses and shifting sunlight as we rumble down the track towards the melee. But a second group has caught it on camera: the cheetah torpedoing through the pincushion foliage, lunging at a luckless springbok, bringing it to its knees. By the time we arrive on the mortal scene she is tamping the stunned creature’s neck with her powerful paw and chirruping for her babies. Three cubs emerge from hiding, downy ears backlit by the dipping sun. Their mother is about to deliver a lesson essential to their survival: the dispatch of felled prey. “She’s a good mum,” says guide Ivan Buregoo. “Look how she’s scanning around for other predators.”

She has a good role model – and a miraculous feat of conservation – to thank for today’s victory. In 2004 her forebear, Sibella, was the first female cheetah to be reintroduced to the Great Karoo after a 130-year absence. Born wild in South Africa’s North West province, she’d been rescued by conservationists after a near-fatal attack by hunters. A long and productive life (by cheetah standards) awaited her at Samara, a private reserve cushioned between Camdeboo and Mountain Zebra national parks in the Eastern Cape. Sibella reared 19 cubs and died aged 14 in 2015. Her descendants are now present in numerous national parks and reserves across southern Africa.

The predator’s return exemplifies the quest by Samara’s founders, Sarah and Mark Tompkins, to rewild a landscape degraded by generations of livestock farming – most famously, Karoo lamb.

“They spice themselves from the inside with ankerkaroo [African sheepbush], which smells like rosemary,” says Buregoo. But this immense semi-desert was once South Africa’s own “Serengeti”, a migration route for herds of springbok, a hunting ground for lion, leopard and cheetah, a refuge for quaggas (relatives of zebras), which were eradicated by hunters in the late 19th century. Barren though it seems, it is in fact a global biodiversity hotspot, wreathing together five of South Africa’s nine biomes. In 1997, when the Tompkinses saw the first of 11 farms that would ultimately comprise their 27,000ha reserve, they fell deeply in love.

“And there began our journey,” says Sarah. “‘Rewilding’ was not part of the lingua franca of the modern world when we started 27 years ago … [The] scientists were telling us that we were facing an extinction debt and … we just chose to put our noses above the parapet and to say, ‘OK, let’s get on with it’.”

Cleared of fences and allowed to rest for a decade, the reserve was gradually repopulated with species including the Big Five – lion, elephant, buffalo, leopard and rhino. Two off-grid lodges – Karoo Lodge and The Manor – and the tented Plains Camp were constructed. Today, Samara and its neighbour, Mount Camdeboo Private Game Reserve, are working with stakeholders like SANParks and other private landowners to create a vast wildlife corridor that will interconnect preserved areas.

“We’ve got almost a million hectares under conservation – that includes reserves, livestock farmers and national parks,” says Marnus Ochse, Samara’s general manager. “[This corridor] will bring us almost 100,000ha of landscape that will hopefully one day be free-roaming, and hopefully [we’ll] see species like wild dogs returning.”

The cheetahs’ success bodes well for wild dogs. Under their mother’s watchful eye, the three-month-old cubs are now going for the springbok’s jugular; tonight they will sleep replete. The amphitheatre encircling this singular performance transforms as we retrace our steps across the fossil-studded basin to Karoo Lodge; sedimentary veins are lit rose gold, violet and magenta. That sheepbush-infused lamb is sizzling on the braai for dinner in the boma, the rising moon illuminating our own feast. Retreating to my suite, one of 10 scattered around the homestead and sleeping up to four guests each, I find the freestanding bathtub drawn and the bed calling. But for a long while I stare out the window, imagining I’m alone in this melancholy, moonlit wilderness.

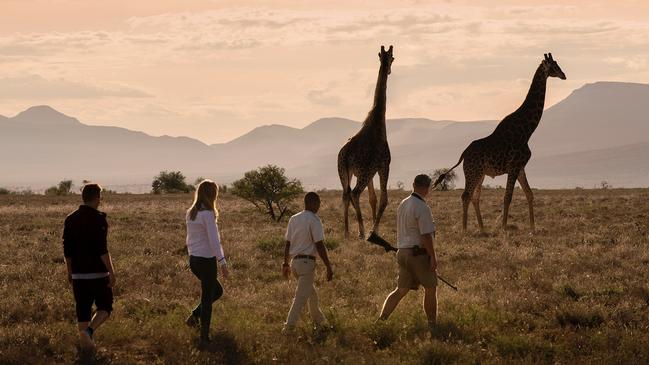

The road to heaven is paved with spekboom (“bacon tree”) and euphorbia next morning as we ascend the ranges. A bokmakierie’s (bush shrike) trill sweetens the air; sunrise gilds the leaves of the wild olives and the ghostly trunk of a shepherd’s tree. Giraffes, which were reintroduced in 2007, bend rather than stretch to browse the stunted acacias. Cresting the ridge, we suddenly find ourselves in the “Serengeti”. Sweet rooigrass (red grass) rolls across the plateau; finely striped Cape mountain zebras graze on the profligacy. Driven to the brink of extinction in the early 20th century, their numbers are steadily rising. A nearby fence demarcates Samara and the 14,000ha Mount Camdeboo; it will be made redundant when that free-roaming corridor is established.

“We’re finding our way forward cautiously,” says Tompkins, “with a considered approach of how it can be done.”

It’s a 30-minute drive along a dirt road from Samara to Camdeboo Manor, one of four restored Cape Dutch dwellings accommodating up to eight guests each (there are also two mountaintop eco-pods). Part of Newmark’s luxury hotels and reserves portfolio, Mount Camdeboo was also once a disembodied collection of farms. Like Samara, it has been regenerated and repopulated with the Big Five and other wildlife.

This bounty awaits us as guide Solly Munnik leads an afternoon game drive. Lions conceal themselves in the thickets; gemsboks’ rapier horns slice the air; a herd of translocated elephants marches self-assuredly through the valley, as though their forebears had never left. A chill wind displaces the day’s heat as we zigzag up the escarpment. Below sprawls the inscrutable valley, above soar buzzards scouting for prey. We have dress-circle seats for sundowners: a ridge line from which we watch the sun slamming into an adjacent mountain and turning the sky into a copper dome.

Back at Camdeboo Manor, the night sky is shredded with starlight. The Milky Way surges like a tide through the heavens, echoing the nearby Milk River when flowing with run-off from the Sneeuberge. Munnik points his laser at Pleiades, also known as the Seven Sisters.

“You can only see six at the moment, because the seventh one went off to get married, as the story goes,” he says. “That was the first eye test – the Romans during the Roman Empire called all the soldiers together and asked how many stars they could see in that cluster. The ones that said they could see seven stars became the archers, because they’ve got good eyesight, the ones that said they could only see six became infantry.”

Sadly, the seventh sister eludes me. But the boma is bright with wood-fire and sweet with those Karoo-scented meats and a local favourite, pap en sous (maize porridge and tomato relish). Swaddled later in my four-poster bed, I dream of shooting stars and flaxen threads pouring like the Serengeti through Rumpelstiltskin’s fingers.

But this dreamy landscape is also haunted by human tales. Eons ago, Khoisan inhabitants left their mark in the rock art secreted in the mountains; later they suffered displacement and European-borne disease. During the Anglo-Boer War, gunshots ricocheted through the gorges. Frost crusts the grass next morning as we pass the remains of a stone kraal where young Boer guerilla Johannes Lotter hid from the British. He and his comrades ran out of ammunition during the ensuing Battle of Paardefontein; they were later executed.

Hideaways of an altogether more salubrious bent teeter on opposite edges of the mountaintop – those eco-pods, each with a queen bed and hot tub overlooking the Camdeboo Plains. They’re fenced, which is just as well, for our path nearby has been blocked by two cheetahs. They’re “reading the menu”, Munnik says – distant herds of hartebeest, blesbok and gemsbok. In winter, they race through snowdrifts in pursuit of their prey, the only place in the world such a phenomenon is believed to have been recorded.

“They go from zero to 100km in less than three seconds,” says Munnik. “See their flattened tails? They use them like a rudder, to take sharp corners.”

But the cheetahs are indolent today, and indecisive about that menu. It is we who must make a sharp turn. Munnik reverses, and doglegs through the grass. It streams behind us like a river of gold as we begin our long descent to the valley floor.

In the know

Samara Karoo Reserve and Mount Camdeboo Private Game Reserve are about 2 ½ hours’ drive north of Port Elizabeth/Gqeberha. The Africa Safari Co’s self-drive Discover the Karoo safari costs $3900 a person and includes car hire, six nights’ accommodation, eight safari activities, entrance to the Valley of Desolation, breakfast daily and all meals while on safari.

Catherine Marshall was a guest of South African Tourism and The Africa Safari Co.

southafrica.net

If you love to travel, sign up to our free weekly Travel + Luxury newsletter here.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout