Hoanib Valley Camp

This incredible lodge emerges from an untamed corner of Namibia with a host of creature comforts – and creatures.

There is no road, to speak of, into Hoanib Valley Camp. The tarmac peters out once you leave the oasis town of Sesfontein, gateway to Namibia’s northern Kaokoland region. It’s little more than a track as it winds through golden plains where springboks graze and ostriches duck for cover in long grasses, their slender necks and heads periscoping the landscape until we’re safely out of the way.

After about two hours, the track veers directly into a wall of towering stone peaks parked here during the collision of the Congo and Kalahari cratons. In the hundreds of millions of years since, water has carved a serpentine route along the base of the mountains, so we simply swap dusty track for dry river bed and drive on.

Each stone-walled corner reveals daunting new aspects of stone and sky until, eventually, the cloistered riverbed opens on to a sandy plain and the most improbable lodge I’ve laid eyes on.

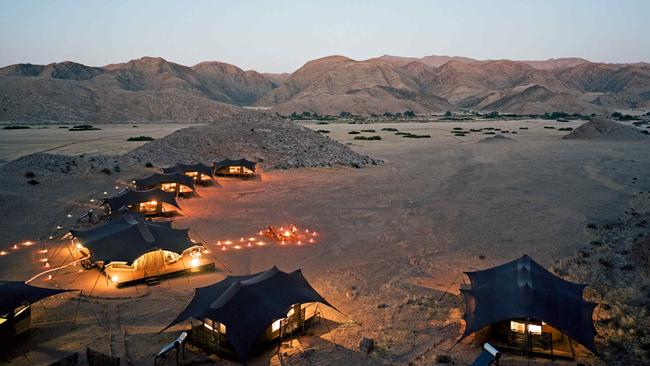

Hoanib Valley Camp consists of seven tents pegged and roped into the desert in an arc at the base of a sheer crag. A circle of deck chairs and Survivor-style torches surrounds a brazier in front. Everything, including the dune-top pool, is angled to take full advantage of the cinematic views.

As I’m struggling to get my bearings in this remarkable place, rich African voices rise up and echo against the stone amphitheatre.

“Well-come to Hwa-nib Vall-eee! Well-come to Hwa-nib Vall-eee …” Ten enthusiastic staff clap, dance and sing me into camp. Manager Petronella Daniels, in braids and sunglasses, leads the chant. It’s hard to imagine a warmer welcome.

We’ve arrived in good time for sundowners but first, a relaxed check-in at the main lodge, which is a canvas pavilion of leather sofas, dining tables and a central bar with coffee machine and all-day snacks.

A tour of my accommodation leads to one of six tents set on platforms above the sand. Inside, the spacious bedroom and living area features a king bed clad in white linens, desk, charging board, pedestal fan and assorted lamps. Rear curtains open to the bathroom, open wardrobe, twin vanities and a separate, canvas-partitioned toilet.

Each tent also has a whistle in case of emergency. “We do have animals walking around,” Daniels assures me. “Like the lions. You never know where they are.”

Kaokoland is an untamed corner of Namibia with, on average, just one person every two square kilometres. It extends from the Hoanib River, which flows sporadically in front of the camp, to the Kunene River on the Angolan border.

How this camp came to be here is easily explained. Natural Selection, formed in 2017 by four guides including Australian Dave van Smeerdijk, runs camps and lodges in Namibia and Botswana in the belief that “tourism, done correctly, can be a powerful tool for conserving and protecting Africa’s last great wild places”.

The site was recommended to them by researcher Dr Julian Fennessy, who camped in this spot for years while studying Angolan giraffes. Hoanib Valley Camp opened in 2018 in partnership with Fennessy’s Giraffe Conservation Foundation; in its first year of operation 30 per cent of profits went to conservation and the local community.

Guests can become citizen scientists by posting photos of giraffes so the GCF can better understand the animals’ behaviour. All camp guides are trained by the foundation so, if 5m tall ruminants are your thing, this is the place. If not, there’s plenty else to awe you.

The setting is the star attraction but guests also come – usually by plane but in my case via a day’s drive from Windhoek – for the impressive though quite elusive wildlife. Drought-breaking summer rains mean the usual array of elephants, lions and hyenas that frequent the camp’s permanent waterholes have ventured deeper into the valley beyond the reach of day safaris.

That’s OK. The human culture’s equally captivating. Camp staff, 80 per cent of whom hail from Sesfontein, are thoroughly entertaining whether teaching me click languages or delivering hearty candlelit dinners on the deck and even, one night, a full braai served in the desert. Big personalities, big smiles, big voices, big hearts.

There’s also the opportunity to visit local tribespeople. After breakfast one morning guide Niclas “Nicky” Rungondo escorts us in a pimped-up Toyota Land Cruiser to meet a Himba family of five wives and four children. Their father and husband is off somewhere in the hills with his goats.

The women, their hair sculpted with red mud and bodies ornamented with goat skins and copious jewellery, are incredibly striking but it’s a toddler who commands my attention. He’s about two and charges towards me, headbutting my knees repeatedly until I worry he might do himself an injury.

Nicky’s mother is Himba so he speaks the language and knows the customs. He’s the ideal interlocutor, pointing out a small pit of smouldering holy leadwood that burns constantly “to keep the connection with the ancestors”. He chats easily with the women, translating my questions and their answers as they massage ochre oil into their skin for a deep umber glow, a mark of Himba beauty.

The youngest wife is 18. The oldest, I think, is 26. Age is an imprecise thing among the Himba. One of them answers: “When it rains, that’s my birthday.”

Returning to camp afterwards, Nicky announces we must detour to rescue another vehicle bogged in the riverbed. But when we reach the river bank there is no bogged vehicle, just a clothed dining table and bar in the shade of a lofty ana tree. Lunch is served, spectacularly.

Such unforgettable moments continue even after I’ve left Hoanib Valley. We’re en route to the next lodge when Nicky pulls sharply off the road into a grove of spiky acacias where camouflaged giraffes are feeding on tender shoots.

There are six of them, including a juvenile and baby, set photogenically against mountains among sculptural trees. Graceful and beautiful, it’s a privilege to witness them in the wild.

Giraffes have become extinct in more than half a dozen countries, and only 10 per cent of their original habitat remains in Africa. This is a moment, among many in the Hoanib Valley, to be treasured.

In the know

Bench Africa arranges self-drive itineraries in Namibia and discrete three-night packages at Hoanib Valley Camp from $6445 a person, including all meals, national park fees, safaris, camp transfers and return scheduled flights ex-Windhoek.

Kendall Hill was a guest of Bench Africa.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout