Death is ever-present on a trip down the River Nile

The ancient Egyptians’ obsession with the afterlife makes for a fascinating journey fit for a pharaoh | WATCH

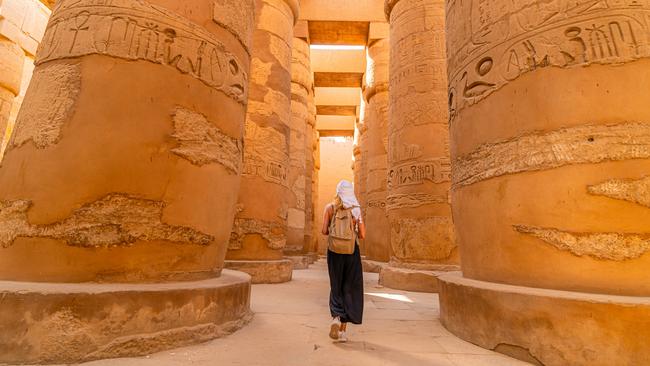

To understand how much majesty, colour and, well, life, can come from death, stand and stare at the walls of the Temple of Karnak and watch the gods shimmer. The ancient spirits of Osiris, Isis, Horus and Anubis glimmer in red, gold and turquoise. They still seem to exude an extraordinary power, unweakened by time and unfaded by Egypt’s fierce heat.

The walls of the Great Hypostyle Hall at Luxor’s biggest temple soar 21m, even in their ruined form. Believed to have been finished around 1224BC, the edifice should be talked about in the same breathless tones as the Sistine Chapel, even if the gods on show are no longer worshipped.

The structure stands strong despite fires, floods and repeated wars over nearly 5000 years. The miracle of conservation and artistry is evident in every niche – the columns with hieroglyphics that could have been carved yesterday; the little sparks of gold in tribute to emperors and pharaohs long gone. Everyone from Rameses II to Alexander the Great, Queen Hatshephut to Jesus Christ, now resides with the Egyptian gods at Karnak. The faces of Greco-Roman invaders such as Alexander, who came to North Africa 300 years before Christianity, are portrayed in tomb drawings alongside the Egyptian deities. Decades later, when Christians hid in the ruins of Karnak from Roman persecution, they painted the Lord, the Virgin Mary and the saints over the hieroglyphics on the columns in the temple’s outer reaches. So many souls and so much history, interlinked. But that is ancient Egypt to a tee; the next life can seem more important than the present.

“There’s very little left of life from ancient Egypt,” our guide tells us as we walk through the ruins. “The houses were mud brick and went with the floods … all that is left is the afterlife.”

Nile River cruise

Death really does follow us down the Nile as my fellow passengers and I take a 12-day journey with Viking Cruises that includes three nights in Cairo and eight days on the river on the operator’s luxurious new 82-passenger ship, Viking Hathor. At every stop there is a monument, great or small, paying homage to the afterlife.

But let’s go back to the beginning, in Cairo. Hail the nine pyramids of Giza, just outside the capital. I’m unprepared for their proximity to the city; hotels and highways are within sight of these great wonders of the world. Their size is something to behold and the ease of access astonishing. I stroll around unhindered and sit on stones laid piece by piece 4500 years ago by thousands of slaves and peasants.

Reasonably close by are even more of these extraordinary mausoleums to the pharaohs. The oldest pyramid, the Step Pyramid of Djoser, is actually in Saqqara, about 20km by road from Giza. The location is also where the tomb of King Unas of the Old Kingdom lies. Unas reigned for at least 15 years, about 2300 years before the birth of Christ, and little is known about him. His pyramid is much smaller than the Giza monuments and its exterior is a bit rough around the edges, rather like a piece of white Toblerone that has melted in the sun.

But climbing inside Unas’s tomb reveals something spectacular. It’s a steep climb down a ramp, an undertaking that proves too much for some in our group, but those of us who manage to make it into that narrow corridor gasp in awe. Despite its age, the interior, which is striking in red and gold, is almost completely intact. And it is enormous, comprising at least five cavernous sections.

Tour guides

The linchpins of Viking Hathor’s itinerary are Hasan and Ghada, a pair of Egyptologists who are with us from the moment we arrive at Cairo’s Conrad Hotel to when we fly home – our very own Nefertiti and Cleopatra. These two women are equipped with the perfect mix of academic smarts and local know-how, and they are determined to show us tombs and temples tourists wouldn’t usually flock to; places off the postcard trail. I’d follow these ladies into any dark tomb anywhere. The duo quickly develops a strong fan base among the Viking guests, who are mostly Americans (although some proudly identify themselves as Texans), with a smattering of Australians and New Zealanders. Apart from a couple of young honeymooners, the demographic is mature but everyone is up for an adventure. And the adventure properly gets under way when we fly to Luxor to board Viking Hathor, named after the Egyptian goddess of motherhood and fertility.

On the ship

My companion and I are in a veranda stateroom, a spacious cabin in pale blue and creamy hues, with a balcony that presents the perfect perch for watching life on the Nile glide by. There are three other cabin categories, including two extravagant Explorer suites more than twice the size of ours, and standard staterooms with picture windows rather than balconies. All feature comfortable beds, stylish decor, good wi-fi speeds, great aircon and strong showers.

It’s a spectacular ship and the food is excellent, overseen by a German chef at the two restaurants – a traditional venue and the more casual indoor-outdoor Aquavit Terrace, which extends to the deck near the pool. There are the expected favourites of spaghetti bolognese and cheeseburgers but an Egyptian-themed evening yields ful medames (a stew of fava beans) and the national dish of koshary, which is essentially pasta, fried rice, vermicelli and brown lentils topped with chickpeas, crispy fried onions and garlicky tomato sauce. At the bar, with drinks at additional cost, reliable favourites of margaritas and negronis and Johnny Walker are popular. The waiters are a mix of Egyptian locals and Viking’s European staff, and the stateroom staff are incredibly efficient and keep everything smooth and spotless as we laze on the sun deck, soak in the plunge pool or explore on shore.

Valley of the Kings

But for all this luxury, more death on the Nile awaits, and it’s directly visible from the top deck of our floating five-star hotel. Luxor’s Valley of the Kings spreads out before us, a vast rocky range that holds dozens of tombs. As we take our buggy car from the security checkpoint to the valley, we can see doors dotting the hillside. These are the tombs of priests, concubines and palace officials who were lucky to secure a resting place close to their masters. Dismounting our chariots, we immediately gravitate towards the queue of tourists lining up to see the most iconic of boy kings, Tutankhamun. But Hasan pulls us the other way. “We will see Tutankhamun … but he is the smallest of the tombs,” she says.

She leads us instead to the tomb of Seti I, who staked his claim as the king of kings; in many ways, he’s the grandfather of the valley. As pyramids went out of style and the royal family moved south from Cairo to Luxor, he set up the dynasty that his son Rameses I and grandson Rameses II would lead to glory and power. Seti’s tomb makes Unas’s back in Saqqara look positively humble.

When the Italian archaeologist Giovanni Battista uncovered it 1817, more than 100 years before British Egyptologist Howard Carter found King Tut next door, there were still paint brushes on the floor. Indeed, some of the interior looks like it was decorated yesterday. Osiris, the god of the underworld and a ubiquitous presence in every tomb I enter, is painted in vivid green. In the hall leading to Seti’s coffin, strong male warriors are presented on the columns with bright brown skin and shimmering armour around their muscled chests. In the room where the coffin lies, a wall covered in gold leaf is adorned at the top with the mother goddess Isis, her wings outspread as if she is going to scoop us up and carry our souls off to the next world.

Tutankhamun’s tomb

Dazzled by Seti I, I head to Tutankhamun’s burial place. It is much smaller; essentially one tiny room, not much bigger than a studio apartment.

“He died so young, he did not have much to take to the afterlife,” Hasan reminds us.

It’s beautiful, nonetheless. The walls are a dark, maudlin blue instead of the red and gold we’ve seen so far. But what is truly different about this tomb is Tutankhamun’s mummified presence. The boy king’s embalmed corpse, returned to his resting place in 2007, is on full display, his withered face visible through the glass. At age 19, Tutankhamun oversaw the beginning of a religious counter-revolution that brought back the old gods that his father, Akhenaten, dumped for one solitary sun god. His tomb, found by Carter in 1922, kicked off widespread Egypt mania in the early 20th century. Most of my travel companions are taking snaps of the mummy but I can’t bring myself to do so. My reluctance is partly fuelled by an irrational fear of the curse associated with Carter’s expedition, but I also feel a need to let this young man continue his journey in peace.

Temple of Esna

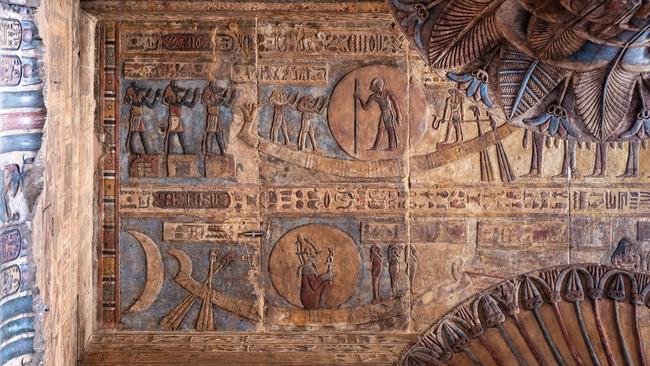

Viking Hathor sets sail for Esna, where our itinerary takes a turn from tombs to temples. Esna is home to the most extraordinary Greco-Roman temple, testament to the Romans’ success at bending the Egyptians to their will. Carved on the walls are scenes of Tiberius, Rome’s second emperor, making offerings to Horus. The ceiling is stunning. It shows the sequence of the moon, with the slowly closing eye of Horus representing each stage from full moon to crescent. On the opposite side in bright blues and purples, we see the full zodiac – Libra, Taurus, Cancer, Scorpio et al, up there with the Egyptian spirits.

Aswan, the southern holiday town where Agatha Christie wrote most of Death on the Nile, brings us to the central myth of the ancient Egyptian religion. And yes, it’s all about death.

Nestled on one of the islands of Aswan and only accessible by small boat is the Temple of Philae. After Set, the god of evil and chaos, murdered her husband (and brother) Osiris, the story goes that Isis took her son Horus to Philae to hide and train for battle against his father’s killer. The ruins of Philae, under threat from floods, were moved piece by piece by UNESCO in the 1960s and 70s and have been painstakingly reconstructed. They have clearly suffered water damage, and lack the colours of previous temples, but are still grand enough to honour the goddess of the Nile and her child.

There are several monuments to the Roman emperors here, but none so tinged with tragedy as that of Hadrian. The emperor’s young male lover, Antinous, is said to have fallen off a barge into the Nile, leaving Hadrian heartbroken. It was rumoured the young man sacrificed himself so the gods would pass his youth on to Hadrian. The devastated emperor left the Nile and went on to develop a cult and build temples honouring his beloved. It seems an appropriately Egyptian kind of response.

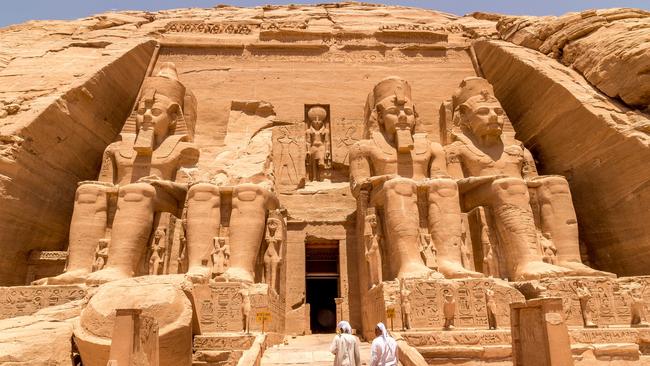

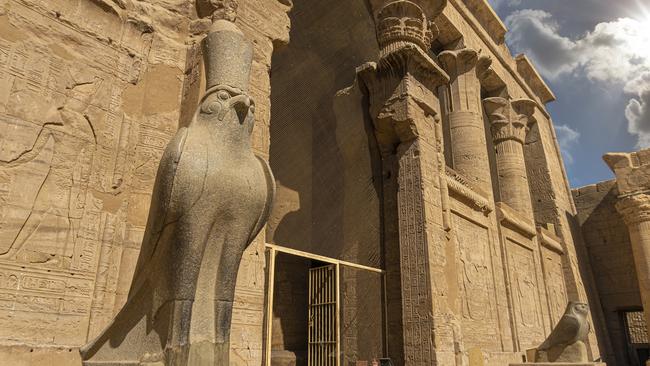

Our last temple before leaving the ship and flying back to Cairo is in Edfu, where the story of Horus and Set reaches its climax. The war between Horus, depicted as a man with a falcon’s head, and Set, who resembles a dog-like creature without human features, is illustrated on the walls of Edfu like a kind of ancient comic book. As Horus goes from panel to panel amassing weapons and strength, and with the help of his ghostly father Osiris, we see Set get smaller to the point of oblivion. It is an epic story of good versus evil.

Back in Cairo, there’s time for one final excursion. Our guides take us to the Coptic Quarter, built by the Romans as a fortress and now the heart of Egypt’s Christian community. In the Church of St Sergius we are led to a cave in the basement where it is said Mary, Joseph and baby Jesus hid for several months as Herod’s forces hunted them down. It’s just a cave – no grand colours here, just a picture of the Virgin and Jesus. But as I stand in the underbelly of this church, it’s as though I am seeing where the story of ancient Egypt ends and the new world begins. After temples and tombs and pyramids devoted to death, here is a simple grotto devoted to the man Christianity says was sent by God to bring new life.

As I enter the chaos of Cairo’s airport, my mind is filled with all I have seen and learned. I have sailed the same river the pharaohs once took on their ships of gold and silver. They often took that same route in a sarcophagus, on their way to meet Osiris. I may not have been heading to meet the gods personally while sitting on the sun deck of Viking Hathor, but it has been a trip down the Nile worthy of the pharaohs.

In the know

Viking Cruises has five boats operating on the River Nile in Egypt. The 12-day Pharaohs & Pyramids itinerary runs from January to May and August to November. It includes three nights in Cairo and an eight-day cruise on the Nile; from $11,195 a person, twin-share, in a standard stateroom. Book by November 15 to fly free on all 2025-27 river voyages.

Richard Ferguson was a guest of Viking Cruises.

If you love to travel, sign up to our free weekly Travel + Luxury newsletter here.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout