Can you name these famous locations where cinema and travel meet?

Movies take us to some of the world’s best-loved landmarks. Take a tour of architectural treasures that have had starring roles and test your knowledge.

The magical quality of life on the big screen creates a parallel universe that captures our imagination. While Hollywood happily-ever-afters may be the stuff of dreams, buildings and landmarks in cinema classics can double as real-world travel attractions. These architectural treasures are ready for their close-ups.

THE RIESENRAD

British film noir classic The Third Man (1949) captures the eeriness of postwar Vienna on location as the heroes and villains of war emerge from the rubble. Orson Welles performs his hypnotic “cuckoo clock” monologue on the historic Riesenrad ferris wheel in the Prater Amusement Park on Leopoldstadt. The 19th-century panorama wheel still dominates Vienna’s skyline, as familiar as sticky torte, a merry grace note to glorious Habsburg imperial architecture. Taking a ride is the best way to see far-reaching views, and try an eccentric dinner experience. While circling the giant arc at almost 3km/h, diners can toast the rooftops with a Gruner Veltliner by candlelight, nibbling on goose liver and Eisvogel brioche above the twinkling lights.

NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY

Audrey Hepburn brings the glamorous outrageousness of Holly Golightly to life in Breakfast at Tiffanys (1961), adapted from Truman Capote’s urban hymn to New York. Nightclubs and glittery cocktail dos are a party girl’s natural habitat, so it is comical to juxtapose Golightly with the Beaux-Arts grandeur and municipal seriousness of the New York Public Library. Hepburn gleefully lights up the cathedral-like reading room, and giggles by the old-fashioned card catalogue drawers while being shushed by a crosspatch librarian. Today, the towering facade on Fifth Avenue beckons travellers to relax in the cafe, cocoon from the hubbub of Manhattan in majestic rooms and see exhibits from the library’s vast collection, such as the Declaration of Independence and rotating archives of artists as disparate as Lou Reed and Virgina Woolf.

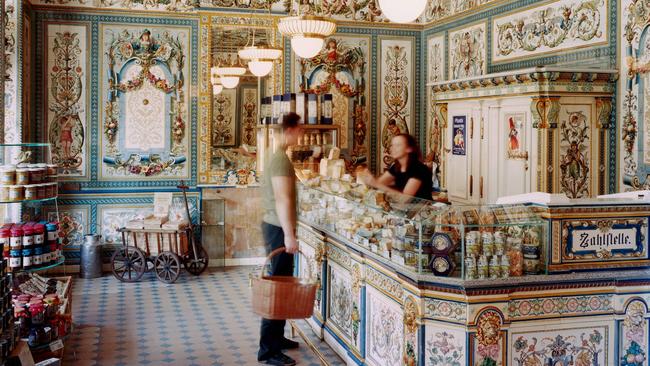

THE PFUNDS MOLKEREI, DRESDEN

The baroque, gilded world of Grand Budapest Hotel (2014) is director Wes Anderson’s fever dream of cobblestoned Mittel Europe. The fictional Mendl’s Bakery serves Courtesan au Chocolat pastries (inspiring viral videos of fans baking frosted choux creations). Epicurean travellers can visit the actual tiny shop, opened in 1892 in Dresden, Germany. Impossibly pretty Rococo handpainted tiles by Villeroy & Boch cover all walls with butterflies, mythical creatures, landscapes and emperors. The self-proclaimed “most beautiful milk shop in the world” serves glasses of fresh country buttermilk and cheese platters, as well as selling newly added milk soap and regional foodie products next door.

THE BRADBURY BUILDING, LOS ANGELES

Blade Runner’s dystopian vision of a futuristic Los Angeles mesmerises from the first frame. The wealthy live in a neon-drenched world of flying cars and 700-storey pyramids, and synthetic humanoids are pitted against actual humans. The otherworldly scene shot in LA’s oldest office block, the 1893 Bradbury Building, blends futurism with 19th-century design elements such as iron railings, cage elevators and a spectacular 15m light-filled atrium, becoming a backlit maze fit for a climactic chase scene. Today, visitors can grab a latte at Blue Bottle Cafe, ritualistically gaze up to the light with other movie fans, and explore the Art Deco streetscapes and shops of the revitalised Broadway precinct in downtown Los Angeles.

TIMBERLINE LODGE, COLORADO

In Stanley Kubrick’s hands, ominous music, architecture, and mountain isolation coalesce to create horror in The Shining (1980). In reality, the same wilderness attracts nature lovers to ski resort Timberline Lodge, the exteriors of which feature in the film. Visitors recreate the spectacular ascent to Timberline of The Shining’s credit sequence, through hairpin bends and pine forest – sans creepy music. Set at an altitude of more than 1800m on the south slope of Mount Hood in the Oregon Cascades, the 1940s boulder and timber showcase is alpine heaven, with year-round snow, hiking, biking and snowboarding. The Shining’s scariest room, No. 237, doesn’t exist – on purpose.

THE GHERKIN, LONDON

When New York director Woody Allen jumped ship to Europe, London became his new cinematic city. Psychological thriller Match Point (2005) features popular London skyscraper The Gherkin. The visual language of Sir Norman Foster’s whimsical spiral of glass panels inspired its signature bar/dining offering. The elevation is a helix and, when viewed from above, it appears as an iris, hence Searcys Helix Restaurant and Iris Bar on Level 39 and 40 (with private dining on level 38). Housed in the only skyscraper to offer 360-degree city views, the seasonal dining is unabashedly British, with locavore dishes featuring UK farm produce. Limitless sparkling wine with afternoon tea amps up devilled eggs and scones; sinful desserts of sticky toffee pudding and treacle tart invite old-school delight.

MONASTERY OF THE HOLY TRINITY, GREECE

Breathtaking locales are as much a part of the James Bond franchise as espionage and beautiful women. One setting in the film collection stands out – the stone forest of Meteora in For Your Eyes Only (1981), where towering, man-made stone monasteries seem sculpted on to gigantic rock pinnacles. In Central Greece’s Kalabaka, contemplative, holy seclusion still exists, but travellers – the new pilgrims – can marvel at the fabled beauty of Holy Trinity, built in the 1400s as a refuge from Turkish invaders and featured in the film. The steep but short 120m stairway (or rock climb, if you’re brave enough) affords sublime views a little closer to heaven.

GRIFFITH OBSERVATORY, LOS ANGELES

James Dean burned into the consciousness of teen America as the ultimate moody boy in Rebel Without A Cause (1955). Interior and exterior scenes were filmed at this gateway to the cosmos on Mount Hollywood, overlooking the Los Angeles Basin; it was the first time a planetarium had been used in a film. Today, visitors can see spectacular live shows with a Zeiss star projector and use the public telescopes. Kenneth Kendall’s bust of James Dean in the grounds, with the Hollywood sign in the background, is Insta-ready.

THE EMPIRE STATE BUILDING, NEW YORK CITY

The romance at the heart of 1957 CinemaScope classic An Affair To Remember drives a melodramatic climax that revolves around New York’s Empire State Building. When dazzling playboy Cary Grant agrees to reunite with Deborah Kerr six months later on the rooftop, it sets a tragic outcome in motion. The magnificent Art Deco skyscraper, completed in 1931, symbolises New York and the hubris of city living itself. The open-air observatory on the 86th floor wraps around the building’s spire, providing 360-degree views of the Brooklyn Bridge, Central Park, the Statue of Liberty and Queens. Want to climb higher? Try the 102nd floor atop what was the world’s tallest building until the World Trade Centre was built in 1970.

ASHFORD CASTLE, IRELAND

The legend of the fiery Irish redhead was cemented by Maureen O’Hara in Hollywood hit The Quiet Man (1953). The idyllic Irish countryside that won over American audiences was filmed in the grounds of Ashford Castle in the riverside village of Cong, straddling Mayo and Galway counties. The Gothic romance of a 13th-century castle, once home to the High King of Ireland and renovated six centuries later by the Guinness family, now lures guests as a five-star hotel and spa. Walk the grounds with the resident Irish greyhounds, try estate honey smeared on piping hot Irish soda bread at high tea, and star in your own Irish fairy tale among towers, parapets and emerald velvet hillsides.

MORE TO THE STORY

Architectural gems also play a role in our onscreen cultural identity. Check out these memorable film locations.

MARTINDALE HALL

Maidens in floaty dresses form the ultimate picture-postcard tableau of Australia’s cinematic Golden Age in Picnic At Hanging Rock. The rarefied European aesthetic is at odds with a mysterious bush landscape, and this 32-room mansion, shot as the girls’ boarding school, is intriguingly surreal. Although the dangerously brooding Hanging Rock is in Victoria’s Macedon Ranges, Martindale Hall lies two hours north of Adelaide in South Australian winemaking district Clare Valley. The house was originally a folly of a wealthy pastoralist, who once replicated the English Valhalla of a polo ground, stables, racecourse and lake. In the film, Martindale Hall is depicted as the domain of the repressive headmistress, Mrs Appleyard. Today visitors can tread the grand staircase where she reigned supreme and wonder at the ornate period chandeliers, mouldings and carvings in this patch of English opulence “out bush”.

NORMAN LINDSAY GALLERY

Australian artist Norman Lindsay represents a bohemian artistic rebellion of another age, when society matrons would clutch their pearls over his sensual paintings. Feature film Sirens depicts Lindsay, played by Sam Neill, in a daydream-like way, painting nudes at his rambling, sun-dappled NSW Blue Mountains estate alongside a cornucopia of curvaceous artist’s models. The movie set and Lindsay’s one-time home at Faulconbridge are now a gallery, museum and tea room. The gravel drive, sculpture fountain and wisteria-festooned veranda create the kind of sandstone idyll that city slickers fantasise about. On display are Lindsay’s Arcadian, pagan paintings and illustrations from his beloved children’s classic The Magic Pudding, right where he created them. Rotating exhibitions, garden recitals and life drawing tuition are in the mix.

THE IMPERIAL HOTEL

The curvilinear Art Deco walls of The Imperial (built in 1940) were put on the map when a little indie film project called Priscilla Queen of the Desert became a global smash and forged a fresh momentum in the LGBTQIA+ movement. Hugo Weaving, Guy Pearce and Terence Stamp sashayed their way around the Outback, but opened and closed the film at the pub. Since 2015, a $6m restoration has given the old girl a makeover and official gay-icon status as a cabaret and dining venue. Priscilla’s Restaurant has a ceviche bar and as many vegan dining options as carnivore – “we don’t discriminate”. Carlotta’s Rooftop (named after the iconic ’60s showgirl) keeps the party going with pizzas, pastas, dips and “dirty Italian disco”.

KINGS CROSS COCA-COLA SIGN

Baz Luhrmann’s work has always been a kitschy tribute to life’s bright lights, so it’s no surprise the Australian director is inspired by the Coca-Cola sign that heralds the gateway to Sydney’s Glittering Mile. Kings Cross is the nocturnal playground for suburbia escapees; a place of cabaret and jazz in the 1950s and neon-drenched bar-hopping in the noughties. Luhrmann has used the sign’s talismanic magic in three films: as a backdrop to two dancers in Strictly Ballroom (1992), rewritten as L’Amour in Romeo + Juliet (1996), and as the exuberant L’Amour Fou billboard in Moulin Rouge (2001). Almost four decades after the original sign was erected, it has been updated with 2km of less power-hungry rope LED lighting. Walk past it en route to the 1950s bijou Piccolo Bar, 1940s food truck Harry’s Cafe de Wheels, and grand colonial mansion Elizabeth Bay House.

Have you visited any famous film sites? Tell us about them in the readers’ comments.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout