Bay of Fires, Wukalina Walk, Tasmania Aboriginal tours

A new trek combining windswept bush and wild, lonely beaches with Aboriginal heritage will open your eyes with each step.

A small object is placed in my hand, forcing me reluctantly to divert my gaze from a vista of seemingly endless, deserted white-sand beaches. What appears at first glance to be a fragment of rock is, on closer inspection, revealed as an ancient, worn stone tool. It has a still-visible cutting edge and, as my fingers quickly, almost instinctively, discover, grooves made by the grips of countless thumbs and forefingers before mine.

In its own way, this little chunk of rock is every bit as spectacular as the expansive view from this vantage point in Tasmania’s furthest-flung northeast corner. It is a veritable pocket-sized time machine; revealing the elevated spot as home to an Aboriginal midden. Further evidence lies nearby in a scattering of shells and bones exposed by the elements; remnants of meals consumed hundreds, perhaps thousands, of years past.

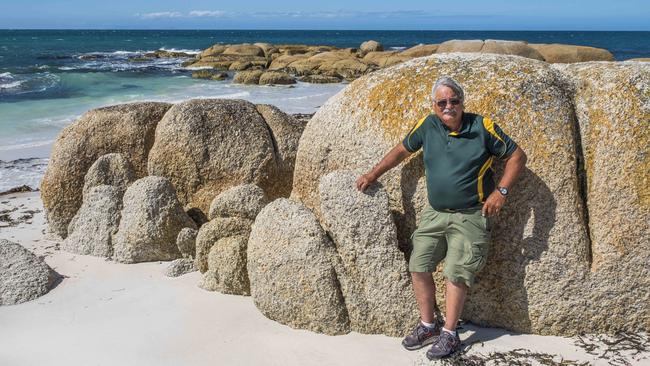

The discovery adds a layer of understanding and intrigue to the pristine landscape in which we are immersed, here in the Bay of Fires. Much the same could be said of this trip, Wukalina Walk, a four-day wander in this little-visited extremity of Tasmania. Launched in January, the walk combines an exploration of landscape — windswept bush and wild, lonely beaches, many punctuated by giant granite boulders, splashed with bright orange lichen — with an introduction to the history and resurgent culture of indigenous Tasmanians. It is the island state’s first Aboriginal-owned and run tourism project, seeking to provide not only a source of jobs and pride for young indigenous Tasmanians but to dispel the myth that their race died out in the 19th century.

Our group of mostly middle-aged white folk from mainland states, as well as a few Taswegians, met a few days earlier at the Aboriginal Elders Centre in Launceston. Before boarding a minibus for the three hour drive to the start of the walk, near Mt William, we are given scones and tea, and a short explanation of the place by chairman of the elders Clyde Mansell. A relative of outspoken Aboriginal activist Michael Mansell, Clyde is more fireside than firebrand. However, his passion and pride are palpable as he describes how the quilts hanging on the centre’s timbered walls depict local Aboriginal history.

One of these appropriately features the Bay of Fires, named by British explorer Tobias Furneaux for the many Aboriginal fires he spied when sailing past in 1773. Another depicts Aboriginal soldiers from World War II; heroes who risked their lives for a country that, on their return, continued to deny them basic rights. Clyde’s tone, as is constant throughout the trip, is gentle and informative, never hectoring or complaining.

This is not what former prime minister John Howard might call a black armband journey through Tasmanian history (literally a guilt trip). Rather, the aim of Clyde’s commentary and the walk itself seems to be to share stories and perspectives, reveal a little-visited and remarkable landscape, and relate it to Aboriginal culture and experience. It is a winning, and long overdue, addition to Tasmania’s burgeoning tourism scene.

On arrival at Mt William National Park, the start of the walk proper, one of our Aboriginal guides, Ben Lord, provides a welcome to country in palawa kani, a constructed language composing elements of many languages that existed across Tasmania before European settlement. The ascent of Mt William — increasingly known by the far more descriptive Aboriginal name wukalina (“woman’s breast”) — is gentle. We barely earn the expansive views from the summit, which extend to the Furneaux Islands to the north and south along the east coast.

The descent takes us on to a new track, made for this walk, through scrub of small eucalypt, banksia, tea tree, boronia and yamina (grass trees). Ben stops occasionally to show us some bush tucker, including the freshest part of the yamina shoots, as well as its hard sap, which he explains was traditionally used to make glue, mixed with kangaroo poo and charcoal.

The walking may be easy but it is a hot day and it’s a relief to reach our purpose-built standing camp, or krakani lumi (“place of rest”). This thoughtfully designed camp of timber huts blends so well into its bush surroundings that it looms suddenly. The external walls are scorched black, softening the visual impact and providing fire resistance. A timber deck with a large central fire-pit leads to a semi-domed sitting area with a ceiling of curved timber shingles. Adjacent is a light, well-ordered kitchen with two long timber dining tables, and an amenities block featuring the cleanest, most comfortable and least odorous drop toilets I’ve encountered, plus welcome warm showers.

The huts are tall timber boxes, one wall of which can be cranked outwards and upwards, providing an instant roof for the small deck. A zipped flyscreen and canvas layer allow this wall to be left open, without inviting slithering and creeping wildlife to your slumber party. Two smaller flaps likewise open on either side for ventilation and light, also with the protection of flyscreen and canvas. Like the shared living area, the ceilings are semi-domes of stained timber shingles.

It is a comfortable, idyllic home for the first two of our three nights, and a short walk to a boulder-strewn beach. Our first dinner sets a high standard: local crayfish, trevalla, wallaby, pan-fried scallops and mutton bird. The last-mentioned, also known as short-tailed shearwaters, are culturally significant to coastal Tasmanian Aborigines, particularly those of the Furneaux Islands. It’s my first taste of this delicacy, which has a flavour akin to chicken but with a hint of fish oil. It’s not unpleasant but not to everyone’s taste.

Day two starts with a morning walk, including to a large, dry waterhole. It appears lifeless, save for delicate, carnivorous sundew flowers. However, wandering over the dried mud it becomes apparent that we have been under observation. Hundreds of tiny thumbnail-sized froglets peer from holes that must, deep within, harbour life-sustaining moisture.

Ben continues our education in edible and therapeutic bush tucker, from the healing properties of the pigface plant to the salty delights of rock-hugging limpets, and we visit the first of several middens.

Another, shorter afternoon walk takes us past Cray Creek and a large black swan nest, sadly devoid of eggs or young, thanks to a resident sea eagle, before an invigorating swim, catching waves amid the granite outcrops. Some of our group try their hands at traditional Aboriginal shell-painting as well as making baskets with kelp and pouches from wallaby skins.

A highlight of that night’s dinner is the dessert of Aunty Gloria’s “doughboy”, a variation on spotted dick, and a letter from this elder providing an insight to her upbringing on nearby Cape Barren Island.

Day three is the longest, walking-wise, covering 17km from the standing camp to Eddystone Point Lighthouse. It is almost entirely along a succession of impossibly beautiful, secluded beaches, most of which have headlands guarded by giant boulders. Each is worthy of lingering, exploring rockpools or marvelling at an array of fantastically shaped granite islands just offshore. We find a shark egg, complete with a tiny shark embryo squirming around inside, but the siren call of the looming lighthouse drives us on.

Our accommodation for this last night is in one of three old lighthouse keeper’s cottages, simply but beautifully restored. We enjoy a quiet afternoon exploring the surrounding land, leased to the Aboriginal Land Council of Tasmania, then enjoy a hearty dinner of wallaby pie.

The fourth and final day is spent around larapuna, as the area around the lighthouse is known, exploring a midden as well as a granite wonderland at The Gulch. A clamber up the lighthouse rewards with views along the coast, north to Cape Barren Island and south past the Bay of Fires. At one point, we encounter a lizard which stubbornly refuses to budge from the path, forcing us to step over or around. “He’s saying: ‘This is my country and I’m not moving for anyone’,” jokes Clyde.

The same could be said for Clyde and Tasmania’s Aborigines, who have survived historic brutalities and modern ignorance to remain a part of this unique landscape. I’m glad of it, and of their decision to share their story with the world, one glorious step at a time.

Matthew Denholm was a guest of Wukalina Walk.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout