Australian novels that evoke their setting

Australian literature can take us places, even when we’re unable to travel.

While border restrictions mean many parts of Australia are beyond our reach, novels have the ability to transport us around the country — and even back in time. This selection is notable for the way each book conjures a strong sense of place.

The Hawkesbury, NSW

To explore the hidden inlets and coves of the Hawkesbury, just north of Sydney, is to time travel back to the wilderness so evocatively described in Kate Grenville’s The Secret River (Text Publishing, 2013). Hemmed in by sandstone cliffs and hills densely cloaked in eucalypts, the waterway seems much as it would have appeared to the fictional William Thornhill, notwithstanding the potent absence of the Indigenous inhabitants. Grenville writes of her protagonist’s journey up the river where he spied the plot of land he would claim for his family. He saw “skinny trees that grew out of the very stones themselves, and what had seemed a dead end slyly opened up into a stretch of river between cliffs”, which were “mouse-grey except where the wind had exposed buttery rock”. Slabs of sandstone had tumbled down and “where the cliff met the water a tangle of snake-like roots, vines and mangroves knotted around the fallen boulders”. I have hiked, cycled and sailed this region. When I’m in the thick of it, with no visible signs of the modern world, I imagine this is exactly how it looked to the Darug people and the settlers who displaced them.

PENNY HUNTER

Blue Mountains, NSW

Mercurial weather and the health-giving properties of the air in the Blue Mountains, west of Sydney, drive the narrative in The Service of Clouds by Delia Falconer (Macmillan, 1997). I always visit Katoomba with a copy in my bag; it is utterly transporting, atmospheric and magical. “To live in that high land is to lose familiarity with the shape of things,” narrator Eureka Jones tells us. “You cannot trust your eyes. In a single day I have witnessed the tremulous birth of the world … I have watched rain fall upwards from the floor of Mount Solitary … beneath sliding veils of vapour, trees have formed soft oceans in the depths of valleys dappled by cold blue shadows in which parrots swarm like tropical fish. When the mists come, the edges of the cliffs blur, rocks melt, chasms close over and streets drop into precipices.” The year was 1907, the Hydro Majestic Hotel at Medlow Bath was suspending its “hydropathic” experiments for the consumptive, love was not “in the air” for Eureka and photographer Harry Kitchings and “lives were lived in the service of … clouds which took the forms of our desires”. It’s a book of rare, uplifting beauty that challenges the reader to view the Blue Mountains anew.

SUSAN KUROSAWA

Outback Australia

A meandering “labyrinth of invisible pathways”, central to “Aboriginal creation myths”, forms the basis of The Songlines by Bruce Chatwin (Penguin, 1987). Those sacred stories tell of the Dreamtime “wanderers” who sang out the names of “everything that crossed their path — birds, animals, plants, rocks, waterfalls” and so brought “the world into existence”. British writer Chatwin admits that in his childhood he never heard the word Australia without “calling to mind … an incessant red country populated by sheep”. The Songlines, written as a travel narrative with a ragbag cast of characters encountered along the way, helps dispel any such notion of empty desolation. And although dismissed by many anthropologists as a mere skimming of Indigenous creation stories, the book has made me look more closely and appreciatively at outback landscapes. A few years ago, flying over Uluru in a light plane, I imagined Chatwin pottering in the desert and thought of the topographical perspective that informs Indigenous painting as I jotted in my notebook: “I see not just the ground but ochre, green and white canvases with dots, swirls and lines of vegetation, riverbeds, the tracery of animal tracks … honoured Tjukurpa stories of country, ancestry and law.”

SK

Northeast Tasmania

Rohan Wilson’s The Roving Party (Allen & Unwin, 2012), a brutal depiction of the systemic slaughter of the island’s Indigenous people, paints Tasmania’s northeast as a forbidding place. Ben Lomond, near Launceston, is a “rise of crag and battlement white with silvered snow. The mountain’s shadow jagged across the fields …” Later on, “stands of gums in blossom, the fiddlebacked acacias and the gauntly made myrtles blanketed the hillside as far as they could see. It was a stretch of forest entirely hostile to folk of any nation, native or not.” There are brittle trees and parched leaves, “tea-coloured water washed up in a lather of foam” and rainforest where everything “was shrouded in moss and every breath brought them the stink of decay”. Even the weather is an affront: “long gusts [of wind] full of the cold of the southern ice lands”; and rain “like stones thrown against the earth, great fistfuls flung in anger, and it was deafening”. This is not the Tasmania of tourism brochures but a place where hikers don’t want to come unstuck.

PH

Adelaide, South Australia

Anna Goldworthy’s debut novel, Melting Moments (Black Inc, 2020), transports the reader from Adelaide — “just a big country town” — to Melbourne and back with a couple of jaunts on the Murray River along the way. Ruby, a farm girl and dutiful wife to a returned soldier she barely knows, struggles to feel at home in her first Adelaide address as a married woman. Goldsworthy’s depiction of the city captures the disorientation I have felt as an east coast girl amid the capital’s featureless expanse, baked dry by ruthless summers. Ruby “gazes along the span of Cross Roads from the Adelaide foothills all the way out to the west and feels the emptiness rush in at her, as if she were living on a road from nowhere to nowhere. As if the entire city were built on a desert, and her fledgling rose garden the thinnest of veneers.” Goldsworthy describes a drive up to Mount Lofty, where the trees are “an effusion of autumn colours: gold and crimson and copper and magenta, splashed across the valley below”. Mildura on the Murray is as exotic a travel destination as Ruby gets during her uneventful life but it is one she returns to fondly in her sunset years. “The river is a sheet of gold, divided only by the dark shape of a pelican, dragging a trail through the water.”

PH

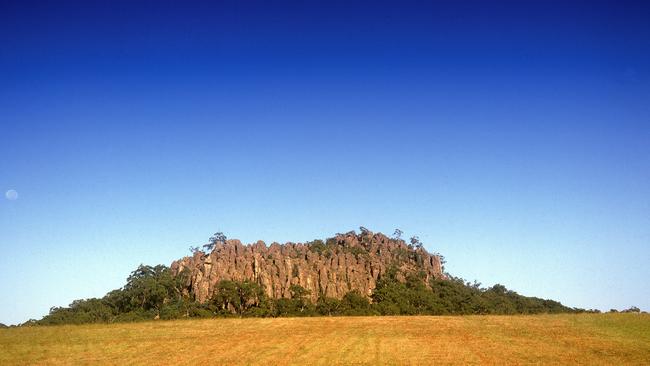

Macedon Ranges, Victoria

Even those who haven’t been to Hanging Rock would feel they know the cluster of rugged, rounded pinnacles, thanks to Peter Weir’s 1975 adaptation of Joan Lindsay’s novel (Penguin, 1967). At first, it’s all pretty white frocks and cakes with cream in the leafy picnic area, where “leaves, flowers and grasses glowed and trembled under the canopy of light; cloud shadows gave way to golden motes dancing above the pool where water beetles skimmed and darted”. But the landscape takes a more sinister turn as Miranda and her mistresses in the mystery leave safety behind. “As the vertical facade of the Rock drew nearer, the massive slabs and soaring rectangles repudiated the easy charms of its fern-clad lower slopes.” Mike, the young Brit who camps out at the Rock hoping to find the girls, feels its menacing presence: “darkness stored all day in its fetid holes and caves seeped out into the twilight and it was night”.

PH

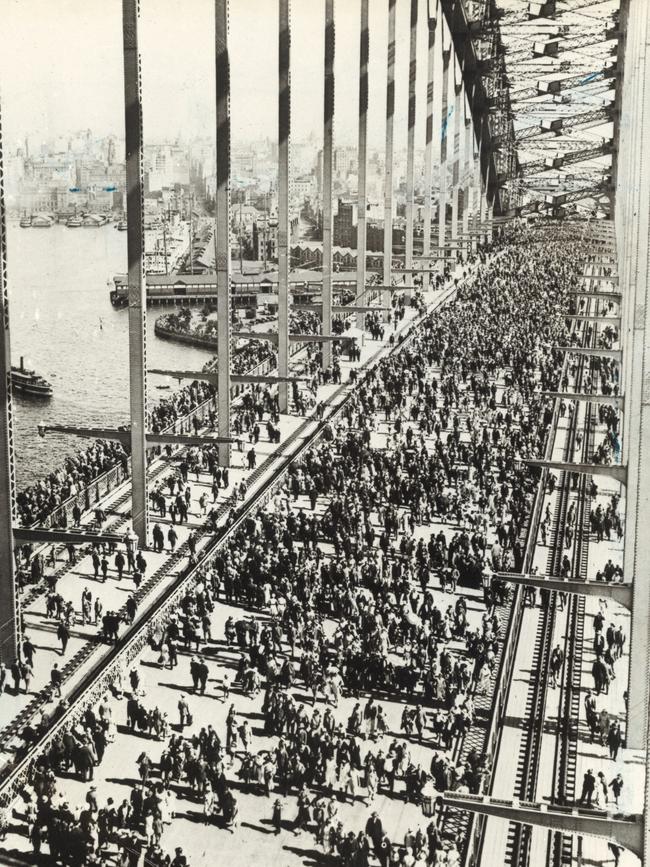

Sydney, NSW

It was March 19, 1932, opening day of the Sydney Harbour Bridge. In Sumner Locke Elliott’s Water under the Bridge (Simon & Schuster, 1977), the Coles family had got up at 3.45am to be the first people to cross when the ribbon was cut. “But they found that thousands had spent the night sleeping and camping out along the approaches so that by the time they arrived … the whole population of Sydney seemed to have collected in the shadows of the pylons.” Mrs Coles then had her doubts about the strength of the feted bridge, and surely would have fainted dead away at the prospect of today’s BridgeClimb tourism malarkey. “All this mob crossing at once, would the bridge hold … They ought to have limited how many could come the first day, they should have had a lottery …” The geography of the harbour city, its social divides, and a slightly bamboozling cast of characters, all star in this wry and witty novel, book-ended by another grand opening, the Sydney Opera House, on October 20, 1973. I can’t walk along Rockwall Crescent or Macleay Street, Potts Point, without looking for featured buildings and summoning passages of Water under the Bridge. Elliott moved permanently to the US in 1948 but “carried in his head a precise map of a disappeared Sydney of the ’30s and ’40s” that informed his work, including Fairyland (1990), his courageous coming-out novel, published a year before his death.

SK

Albany, Western Australia

Tim Winton renamed it Angelus but the southwest port city of Albany, with its old whaling station and wild coastline, has formed a recurrent backdrop to his fiction. It was his home for three crucial years from the age of 12. In The Turning (Picador, 2004), Winton’s collection of 17 interconnected short stories, the bleak beauty of Western Australia is matched by the frailty and flaws of his characters. We smell the smoke from beach bonfires and the pungent odour of fishing forays for flathead and whiting. We see a surfer hang in a wave’s “churning guts” before being spat out and, further west, the air “turns pink with the flying dirt of the desert, pink and corporeal”. Roads are “marked with blown tyres and blown roos”. Two young men escape Angelus in a Kombi van, heading north, reaching the “crappy subdivisions” of Perth and beyond “into vineyards and horse paddocks with the sky blue as mouthwash”. They end up at a vast, shimmering pink lake that “suddenly looks full of rippling water … the sun flattens itself against the saltpan and disappears. They sky goes all acid blue and there’s just this huge silence. It’s like the world’s stopped.” It’s the kind of writing that fuels the desire to get in a car and drive.

PH

North Queensland

Alex Miller’s Journey to the Stone Country (Allen & Unwin, 2003) sees Annabelle Beck, the daughter of a cattle farming family, and Jangga man Bo Rennie travel back to the country of their connected childhoods, south of Townsville. The coast makes an intermittent appearance. In town, there are jacarandas, wattle birds among the bottlebrush flowers, “the glossy foliage of Bowen mangoes … and the lazy drift of smoke from the cane fires”. But it’s out in the bush where Miller’s words paint vivid pictures. Ridges are “littered with shattered upturned strata of sedimentary rocks like the old bones of the world exposed, the forest open and sparse, the trees small, twisted and hungry”. At an abandoned property there is “the smell of the river. The murmur of the water over the rocks like voices, hushed and conspiratorial … distant lightning from the leading edge of another weather system, pale and elusive against the starlit sky, playing along the crests of the ranges.” The ancient, sacred country of the Jangga is shrouded in mystery, a place of “concealed valleys and sudden strange tenements of stone”. The reader senses Miller has an intimate relationship with this land, as though he too has spent weeks kicking up the dust of its backroads.

PH

More to the story

The Australian’s literary editor Stephen Romei suggests 20 novels that evoke their setting.

NSW: Eucalyptus by Murray Bail; My Brilliant Career by Miles Franklin; Kangaroo by DH Lawrence

Victoria: Picnic at Hanging Rock by Joan Lindsay; True History of the Kelly Gang by Peter Carey

Queensland: Johnno by David Malouf; Carpentaria by Alexis Wright

South Australia: From the Wreck by Jane Rawson; Storm Boy by Colin Thiele

Western Australia:Jasper Jones by Craig Silvey; Shallows by Tim Winton; The Golden Age by Joan London

Tasmania: The Roving Party by Rohan Wilson; Bruny by Heather Rose; The Hunter by Julia Leigh; Death of a River Guide by Richard Flanagan

Northern Territory: Songlines by Bruce Chatwin; We of the Never-Never by Jeannie Gunn

ACT: The Memory Room by Christopher Koch; The Fog Garden by Marion Halligan

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout