Antarctic cruise: a Viking voyage to see icebergs, penguins and more

Crossing the formidable Drake Passage is a small price to pay to see the frozen wonderland of Antarctica and its myriad inhabitants | WATCH

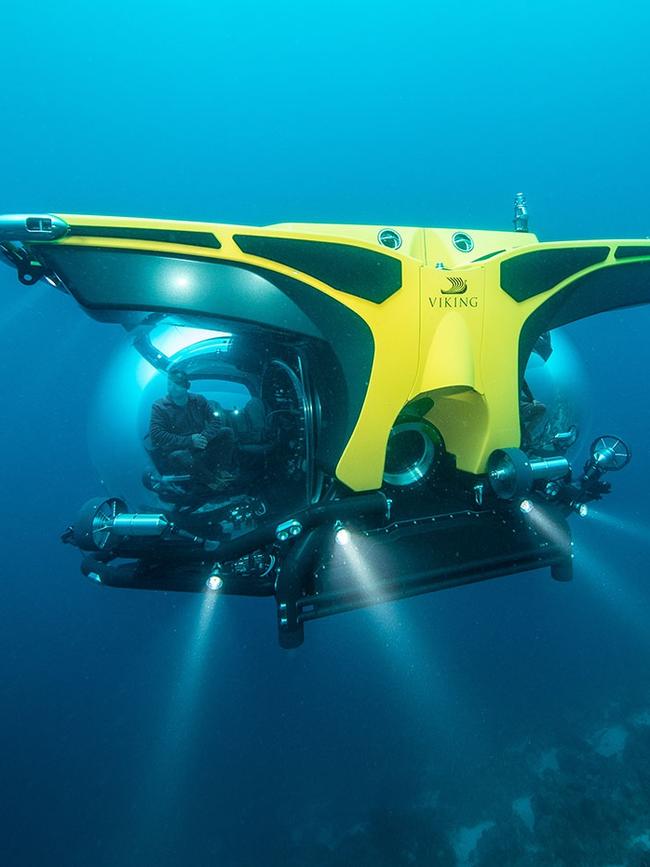

We are close to 100m deep and the submarine is shining a column of light through the deep blue water outside our acrylic bubble. Mostly we can see tiny bright fish scales and specks of “marine snow” floating through the icy water. But there are also transparent creatures; krill, their bodies pulsing past the light. Soon we have reached the sea floor and a fairy garden of delicate flora and minuscule see-through fish darting in and out. There are anemones and sponges, small soft corals, lollipop sponges, sun stars and feather worms. Our pilot is confident we are the first to survey this small site. After all, we are in the depths of Antarctica, at the bottom of the sea, at the end of the Earth.

It is a miracle of modern travel that ordinary passengers aboard the Viking Polaris expedition ship can take a submarine ride in such a remote location. Just over a century ago, this was the exclusive realm of explorers such as Roald Amundsen, Robert Falcon Scott, Douglas Mawson and Ernest Shackleton. Their heroic feats of endurance, their stoic forbearance, their incredible inventiveness and, for some, the tragic consequences, gripped the world’s imagination. Put any one of them aboard this ship on its luxurious 14-day expedition to Antarctica and they would have snorted with disgust at the breakfast buffet, the heated floors in the bathrooms, and the spa treatments offered beside the warm vitality pool. They might, however, have respected the science program carried out on board.

Polaris’s two yellow submarines (named after Beatles Ringo and George; Paul and John belong to sister ship Octantis) are part of the cruise line’s advanced research program, which includes partners such as the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in the US, the University of Exeter and the University of Western Australia. This is not science-washing: the submarine dives, for example, have led to a paper on sightings of giant phantom jellyfish, which have a bell about a metre wide and 10m-long tentacles. These creatures have been seen only 115 times in the world in the past century, mostly at great depth, but in the Antarctic they have been spotted four more times at much shallower depths by those diving in the Viking submarines. So is it science or tourism? Viking claims it can be both, and that’s a big part of the company’s appeal to curious, adventurous travellers who have Antarctica on their bucket list.

There would be few, however, who come to Antarctica to see jellyfish. For who can resist the lure of penguins, humpback whales, wandering albatross and the occasional Weddell seal?

My voyage began in Ushuaia, at the southern tip of Argentina in Tierra del Fuego, the “land of fire”. The November 2022 cruise is one of the vessel’s first outings; it was launched at the end of September as the second of Viking’s expedition ships, joining the identical Octantis in cruising the iceberg-laden waters around the Antarctic Peninsula.

For many aboard the ship, which can accommodate 378 guests, this is the trip of a lifetime. And Antarctica does not disappoint. It was Norway’s Amundsen, the first to reach the South Pole on December 14, 1911, who described the landscape as like something out of a fairytale. It is stunningly beautiful; a study in white. Sun spotlights gleaming banks of snow. Pale mist envelops a nunatak, the peak of a mountain protruding from the icy cold glare of a glacier. Icebergs reflect shades of blue from deep teal to dirty grey. The cliffs that calve these giant blocks seem to have the texture of sparkling chalk. Boom! We hear before we see the puff of white that signals an iceberg being born, slipping away and splashing into the ocean, setting off a shower of snow. The privilege of that moment, for we are among the relative few to have witnessed this scene, repeated endlessly through millennia. Offset against the white are the chocolate tones of rocky mountains, and the dark brown of penguin rookeries coloured by trampled guano. Even the wildlife selects a similar palette of pure reflected light and stormy grey-brown, with the occasional flash of an orange beak (the snowy sheathbill, about the size of a chicken) or the pink of gummy feet (the comedic gentoo penguin).

There are myriad ways to experience this extraordinary environment aboard Polaris. The ship has 189 outside staterooms, each with a “Nordic balcony” of floor-to-ceiling glass. The top half of the window can be lowered to allow fresh air in and offer the best view of the landscape. Binoculars are provided so you don’t miss a possible sighting of a bird or whale. You can promenade around the ship on Deck 5 or pull up a lounge chair in the Living Room or the Explorer’s Bar to survey the scenery. Those are the passive options. But there is also a range of craft to bring you closer. This is one of the differences between other cruises and an Antarctic “expedition”. The whole point of this ship is to get you as near to the freezing landscape as possible. And so there are Zodiac cruises and landings, submarine ventures, a dozen kayaks and a speedy military-style Special Operations Boat with shock-absorbing seats to take the whack out of the waves.

Zodiacs are the workhorses, shuttling groups of about 10 passengers each to shore, driven by a guide likely to be a marine mammal specialist or an ornithologist able to provide a running commentary on the wildlife. Did you know whales keep half their brain active while they sleep?

Our first onshore stop is on day three of the journey, visiting a penguin rookery on Half Moon Island, part of the South Shetland group. I arrive dressed in the ship-provided uniform of black waterproof pants, black gumboots (on loan), and a red parka on top of a blue puffer jacket (to keep). Scrambling on to land as a group, we look like an invasive species, easily identifiable by our awkward gait, brightly coloured upper bodies and almost useless hands encased in thick black gloves. We are totally unsuited to the environment, unlike the chinstrap penguins that rule this roost. In the middle distance is a lone Weddell seal, basking in the snow. Up at the rocky peak, the penguin colony is in full swing. We can hear the squawking conversation as they reach their long necks to the sky, shake their beaks and deliver an ecstatic cry. Our guide says it’s their way of recognising their mate or delineating their territory. We lumber around in thick boots, clinging to ski poles to stop us slipping. Early in the season, the snow is slowly melting. We pose for pictures, our cameras encased in thick plastic in a bid to prevent them “freezing” in the cold.

Marching back down our “people highway”, set out with orange poles, we return to the Zodiacs and the safety and warmth of the mother ship. Surely there is no more apt term for the vessel that acts as our sanctuary here. Back on board, classical music plays over the sound system, a backing track for the seabirds that skim across the water and past our windows. The divide between them and us feels vast. We require so much protection against the elements when we venture out beyond the insulated barrier. They, on the other hand, are perfectly adapted to their environment.

As it begins to snow in earnest, I can still see rugged cliffs of ice in the distance. Is that Antarctica proper? The far-off dream beyond the nearby Half Moon Island? A storm is coming in. Soon we will slip away. The penguins won’t miss us at all.

By day five of the journey many passengers are anxious about their chances of landing on the mainland. Can we say we’ve been to Antarctica if we haven’t set foot on the peninsula? This was supposed to be the day for that landing, but the ice has foiled us. Disappointment is a theme of Antarctic expeditions. Think of Mawson watching the Aurora sail away from his base, condemning him to another winter of darkness. Unrelenting weather is almost always to blame when plans go awry. On this day it’s ice that sets us back, but also ice that’s responsible for one of the most awe-inspiring sights of the journey. Late in the day our ship becomes surrounded by brash ice, a thick layer of ice fragments that creates a spectacular setting with the sun’s weak rays filtering through grey clouds. It is by far the most amazing scenery of the voyage. Even at 11pm, the light is strong enough to offer a soft white glow across the snow-covered land outside the window. It is soft and peaceful. Pristine. Profound. Perfect.

And yet … there is more to do. On day six, we are still not able to go ashore. Instead, we make a discovery. Searching for the elusive landing site, we instead come across an outcrop that appears to have had no previous visitors. Breakwater Island has a population of gentoo penguins but, according to the International Association of Antarctic Tour Operators, has never been visited by humans. The crew members who cut chunky steps into the ice cliff to allow us to land are the first to walk on this tiny island. It’s yet another reminder that we are but short-term interlopers in this place.

By day eight, it’s looking increasingly unlikely we will make it to the peninsula. Our daily briefings in the ship’s Aula lecture theatre (modelled on the great hall at the University of Oslo, where Nobel prizes were once awarded) include weather maps coloured in harsh tones of purple and orange that indicate strong winds and low visibility. Captain Margrith Ettlin has 20 years of experience in this region and isn’t about to take risks. As Shackleton famously once wrote to his wife, “better a live ass than a dead lion”. Pressure is building on expedition leader Marc Jansen but he shrugs it off, instead accentuating the positive while organising a visit to Damoy Hut in Dorian Bay at Wiencke Island. The shack, established in 1975 to support the airstrip at Damoy Point, was last occupied in 1993 and is now a time capsule of Antarctic history. Inside, cans of food stacked neatly on shelves and clothes laid out in the bunkroom give the impression someone left just minutes ago. Nearby at Port Lockroy is the only post office in Antarctica, staffed this year by four women chosen by the UK Antarctic Heritage Trust.

Finally, there is a plan. Day nine is our last chance, and we will take it. This morning I am part of a Zodiac armada funnelling guests on to the shore in a military-style operation that will allow everyone to step on to the mainland and have the photo to prove it. The exercise starts at dawn; crew have shovelled out a platform in the snow at the shoreline near Base Brown, Argentina’s research base on the peninsula, to allow everyone a brief moment on land. When I say “moment” I mean 30 seconds. My Zodiac carrying 10 passengers turns around our landing in five minutes and five seconds, pictures done and heading back to the ship. The weather window is incredibly tight. We need to get out of here and run ahead of the storm moving into the notorious Drake Passage. We had the “Drake lake” on the way down; now for the “Drake shake”, with 7m-8m swells.

Yes, I get seasick. But after the wonders of medicine I am well enough to go for breakfast in the ship’s Mamsen’s cafe, where there are traditional waffles, porridge, cinnamon buns and Norwegian treats. Did I mention the buffet at the World Cafe, the sublime Italian food at Manfredi’s, the steaks at the grill, and the sushi? And while we were waiting for the weather to improve, I submitted to a comforting Hygge massage in the spa. Then there’s the ship’s library of 5000 carefully chosen books, plus the science and history lectures in the Aula. And the citizen science projects, such as sampling water for microplastics.

My mind is filled with memories: the five fin whales spotted off the bow; the morning that snowy sheathbills peered through the lecture hall windows; the day we spotted at least five humpback whales spouting at the front – no, the back – no the side – of the ship, and; the petrels flanking us as we sailed back to port.

Back in Ushuaia, in the shadow of the Andes, I would happily go back for more. My red parka is at the ready.

IN THE KNOW

Viking Cruises operates Antarctica expeditions ranging from 13 to 19 days, or longer on itineraries that incorporate other destinations. The 13-day Antarctic Explorer voyage sails January-February and November-December next year; from $17,295 a person, twin-share, in a Nordic balcony cabin. Book by November 30 to save up to $2000 a couple unless sold out prior.

Petra Rees was a guest of Viking Cruises.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout