2022: When thin is in, and self-esteem is out

Self-destructive beauty standards, sleep deprivation and unrealistic, waif-like thinness has throttled its way back in style.

Self-destructive beauty standards, sleep deprivation and unrealistic, waif-like thinness throttling its way back in style.

This is an opinion piece.

There’s a lot that you learn when you restore your relationship with the body after seeking every way to destroy it. Nutritional requirements, coping mechanisms, chants that range from “I am worthy” to “take up space”.

What is not mentioned, however, is the relentless fodder of imagery forced down your throat that (size) zeros in on a vicious portrait of beauty.

Put succinctly: ‘thin is in’, and it’s been proven no more viscerally than 2022’s trend cycle.

In the past ten months of this year alone, the resurgence of trends from the decades past - the 90’s heroin chic, the 00’s Y2K and the 2010’s Indie Sleaze - have all had one unifying thing in common: self-destructive beauty standards, sleep deprivation and unrealistic, waif-like thinness throttling its way back in style.

September marked the beginning of fashion month, and the 10-year anniversary of my recovery from anorexia.

The spectacle of the cross-country month of fashion flourished once again after a pandemic-induced hiatus. Brands commented on the state of the world around us: Moschino toyed with inflation, fastening pool toys to luxury garments, Balenciaga stomped through a mud-encased catwalk symbolising the plight of worker and labour rights and JW Anderson paid homage to the death of Queen Elizabeth II.

And while emerging and established labels included designs and models that defied the industry’s staple “size 0” look, the stride toward body inclusivity fell spectacularly short.

An endless amount of think pieces sprung up in response, targeting the toxicity of the trends, many of which sought a scapegoat.

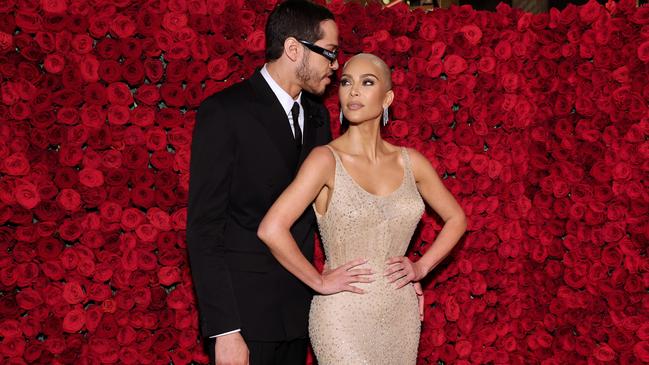

The catalyst was pinpointed to Kim Kardashian’s arse - or lack thereof - after the star’s dramatic weight loss to wear Marilyn Monroe’s dress ignited a furore on social media, only to inspire as much condemnation as it did copycat appearances.

There is a reckoning bubbling with society’s obsession with thinness, but the push for broader representation of physicality remains in its infancy.

For every Precious Lee appearance, “Curve Edit” show or adaptive clothing line that breaks the mould, there’s a low-rise jean or micromini movement reminding us that the thinness fetish never really went away.

It’s no longer a question of what insecurity our society stokes when it upholds these ideals of beauty, but the kind of violence it’s inflicting.

I’m aware it may seem hyperbolic to liken a spray-on Coperni dress to an influx of self-hatred, and it’s probably down to the fact that as a society, we’re very comfortable glamorising eating disorders, and uncomfortable discussing them.

So let’s discuss them, not in numbers that trigger copycat behaviour, but as discussions that trigger genuine change:

Anorexia has the highest mortality rate of any mental illness. The prevalence of eating disorders is as common as substance abuse in this country. The rate of eating disorders have increased almost six-fold since the late ‘90s. Every year, 4% of Australians are living with an eating disorder, a third of which begins in adolescence.

I have been that statistic, and it’s a number that carries more weight than any scale or measurement ever will. The heartbreak of a loved one’s face when they see you waste away, the moments missed with friends over a meal, the words you starve yourself out of saying because you’re incapable of discussing the emotions you experience lingers in the memory longer than a micro-mini skirt trend will.

For as long as the body remains the accessory, the clothes lose all of their artistry.

In the past decade, I have marvelled at the models and designers that have refused to accept the notion “thin is in”, sauntering down a loaded catwalk in true attempts to reshape industry attitudes.

Amid all the pain that prescribed images of beauty can bring up in people, it’s a positive reminder that there is a push for a future.

Heroin chic, hopefully, will fade out of the fashion cycle like a purple lip stain on a night out. But body positivity and a push for inclusivity must be perpetual, so we get to a stage where we can simply look at a show and say: “what a fucking great outfit.”