The secret life of Grace Tame

The former Australian of the Year wants you to know she's more than just her trauma.

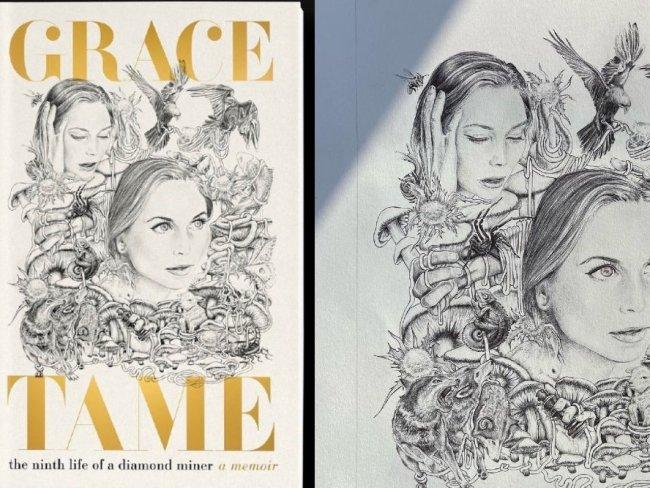

A fervent reclaiming of a personal narrative, from a woman who demanded she be allowed to speak.

Grace Tame doesn’t want to be known just as a survivor of child sexual abuse.

That is, of course, the reason she rose to fame. And her new memoir The Ninth Life of a Diamond Miner doesn’t shy away from the details of her gruesome and repeated assaults at the hands of an unremorseful abuser.

But she wants you to know those details haven’t defined her. She has advocated for survivors, advocated to repeal gag laws, and resisted those who insist she needs to forgive the man who abused her. But she has also won awards for her art, lived with diamond miners in Portugal, and once married the kid from The Cat in the Hat.

The Ninth Life of a Diamond Miner, published today, is brimming with anecdotes from Tame’s life and family history – some bright and glittering, and some dark.

It is a fervent reclaiming of her personal narrative from a woman who demanded she be allowed to speak.

The first marriage

Before Tame met her fiancé Max Heerey, to whom she got engaged earlier this year, she was briefly married to Spencer Breslin - Abigail Breslin's brother, who played the ratbag kid from Cat in the Hat.

They were married in 2017 in an Elvis-themed wedding. Breslin was Elvis; Tame was Priscilla, dressed in a silvery cape-dress pictured in the dozens of family photos included in the book. The ceremony, held on a farm outside Los Angeles, California, was officiated by an aviator-wearing friend in a satin jumpsuit.

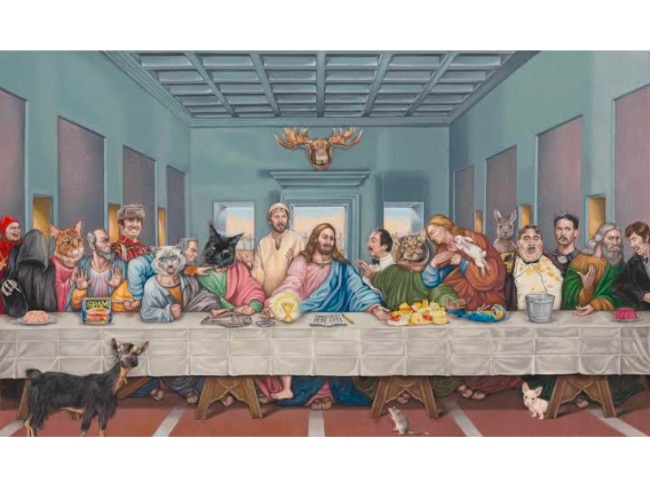

The Last Supper

In yet another surprising celebrity connection, Tame includes a Last Supper parody painting she created for Monty Python actor John Cleese. Her artistic talents are better known now than they were a few years ago – she illustrated her memoir's cover with a Woolies biro, after all.

Still, the artwork is magnificent. Jesus sits alongside Manuel, the Grim Reaper, a few stray dogs and cats, and a kangaroo. On the table, a can of Spam and a dead parrot.

Tame is critical of Cleese for his support of JK Rowling’s anti-trans rhetoric. Still, she writes, he is “just another human being” and was something of a father figure, who loved the painting she did for him.

The loneliest night of her life

One of the loneliest times in Tame’s life, she writes, came at the peak of her public visibility – when she won Australian of the Year.

As Australians rallied around the first public survivor of child sexual abuse to win the award, Tame said just one person was missing.

“The one person who couldn’t be there to share it with me was me when I was a child,” Tame wrote of the evening. “She was hidden from everyone’s view.”

Such is the nature of trauma – often, affected people experience difficulties not as themselves, but as the person they were when they became traumatised. Tame, in the award’s aftermath, struggled to sleep. She lost weight and, with it, her period, in what she describes as a fight against womanhood.

“In those final moments of silence, I found myself. The fifteen-year-old girl in her uniform. And I sat with her. I held her. I cried.”

Nine Lives of a Diamond Miner is a confronting read – but, scattered with moments of levity, it shines.

“If a truth is not told on your own terms, it is not your truth,” Tame writes. And, in a parting message to her fellow survivors: “May these words bring you home.”