Opinion: It's time Australia knows our story

One of the most eminent legal minds in the country writes exclusively for The Oz outlining what needs to be done to move on the most critical Indigenous issue of our time.

One of the most eminent legal minds in the country writes exclusively for The Oz outlining what needs to be done to move on the most critical Indigenous issue of our time.

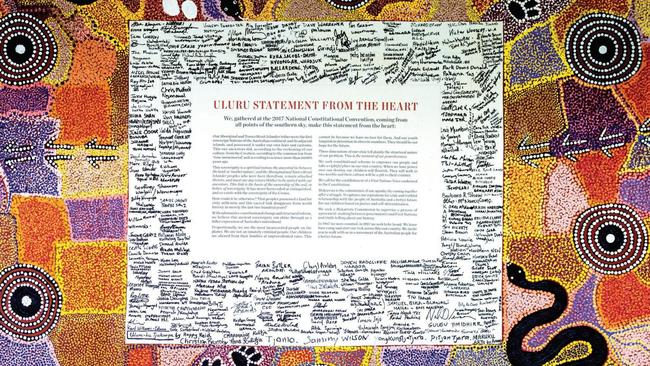

The Uluṟu Statement from the Heart is occasionally mistaken as merely a one-page document, when it is the historic invitation from First Nations people to the Australian people to “walk with us in a movement of the Australian people for a better future”.

But it is more than those powerful words that set down the logic of the primary reform, a constitutionalised Voice.

The Uluṟu Statement in totality is closer to 18 pages and includes several pages of the legal reasoning for a constitutional voice and also a lengthy narrative called “Our Story”, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander story of Australia.

It developed from an earnest question in the first dialogue in Broome: "Don’t they want to know who we are and what we have been through?"

“Our Story” is drawn from the voices of the men and women of the Uluṟu dialogues from all corners of the Southern Sky.

In each dialogue the desire to talk about Australian history emerged organically as many wanted to talk about Australian history before they talked about the Constitution.

The following is extracted from “Our Story”, from the Ross River dialogue in Central Australia, that conveys an Aboriginal perspective on how it feels to have a one-sided history of Australia that excludes our stories:

"Participants expressed disgust about a statue of John McDouall Stuart being erected in Alice Springs following the 150th anniversary of his successful attempt to reach the top end. This expedition led to the opening up of the “South Australian frontier” which lead to massacres as the telegraph line was established and white settlers moved into the region. People feel sad whenever they see the statue; its presence and the fact that Stuart is holding a gun is disrespectful to the Aboriginal community who are descendants of the families slaughtered during the massacres throughout central Australia. (Ross River)."

There are two striking things about the discussion on truth-telling in each dialogue.

The first is that no dialogue wanted a truth-telling process to delay constitutional recognition. Many spoke of Bob Hawke’s delay in granting substantive rights decades ago as he “kicked the can” on structural change down the road in favour of a never-ending and inchoate process of reconciliation.

The second striking thing about truth-telling in each dialogue is hearing how law and policy drove the dispossession. Too many believe it was a lawless, frontier period. When in fact law and policy from colonial governments to governments today have dispossessed and colonised First Nations peoples.

While there is enduring mythology in the nation today that asks of the history of Indigenous peoples: "Why Weren’t We Told?" The fact is, we were told. By our lawmakers. It was in plain sight.

The database we have pioneered and developed in partnership between UNSW Indigenous Law Centre, Faculty of Law and Justice and the Public Interest Advocacy Centre is aimed at archiving and promoting to the Australian people, and a future Makarrata Commission, the depth and breadth of law and policies that cumulatively evidence the “truth”.

The pilot for the database is New South Wales, the epicentre of the dispossession.

The database has collated for future truth-telling the legal framework, piece by piece, what the dispossession looks like as the pastoral economy expanded across the colony. This was done through land and property laws, hunting and fishing laws and regulations, language prohibitions, eventually child removals and many other ways and means utilised by the colony and then the state.

The heavy-lifting of the forensic work required to bring the Toward Truth project to life has been led by a group of young indigenous lawyers and law students, under the skilled supervision of the PIAC team as well as many of the corporate law firms that endorsed the Uluṟu Statement from the Heart years ago in 2017 who have allocated researchers and resourcing to do this work.

Their tactile commitment to the realisation of Uluṟu invaluable.

The regional constitutional dialogues are an Australian democratic innovation.

So too the PIAC ILC Toward Truth database. It is the first of its kind, aimed at educating the nation on its own story.

Professor Megan Davis is Pro Vice-Chancellor Indigenous UNSW and a UNSW Professor of Law.