The best books coming in 2023

Chief literary critic Geordie Williamson rounds up most mind-expanding, mood-altering titles to be released for your reading pleasure over the next 12 months.

Chief literary critic Geordie Williamson rounds up most mind-expanding, mood-altering titles to be released for your reading pleasure over the next ​12 months.

As we all know, reading is the noblest and least offensive of addictions. So in that spirit, let this roundup of books to look out for in 2023 serve as a guide to the replenishment of your supply of the literary Good Stuff over the coming year.

This list comes with the usual caveats. It is an idiosyncratic, unsystematic and frankly partisan selection, made from an immense library of potential titles.

As such, it is filled with shameful absences and gaping blind spots, the overhyping of established names and underappreciation of titles whose success no one can anticipate. To all the out-of-nowhere debuts and sleeper, word-of-mouth hits, a thousand apologies in advance: I know you’re out there, even if you’re not in here.

But with that bit of pre-emptive auto-criticism out of the way, please enjoy this collection of informed guesses at the most mind-expanding, mood-altering titles of the next twelve 12 months.

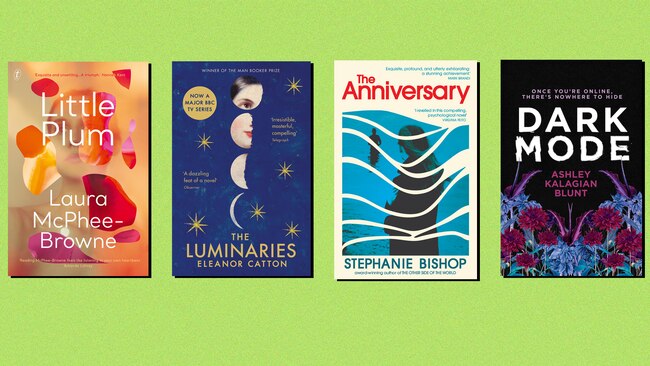

Little Plum by Laura McPhee-Browne (Text, February) is a mediation on expectant motherhood and the second novel by social worker and author of last year’s prize-magnet of a debut, Cherry Beach. Reading it, says Amanda Lohrey, “is like listening to your own heartbeat”.

Across the ditch, the miraculously talented Kiwi author Eleanor Catton arrives with a new novel almost a decade after her Booker-winning The Luminaries. Birnam Wood (A&U, April) is a literary thriller about a guerrilla gardening collective that takes over an abandoned farm on the South Island in which an American billionaire also has an interest. Expect the usual genius-level play with language and idea.

In that same month, Hachette releases a new novel by Stephanie Bishop, our local Catton equivalent. The Anniversary is slated as a novel about writing and desire: two subjects on which the author and incoming professor of Creative Writing at East Anglia has proven form.

Upstart outfit Ultimo Press continues to impress with its commitment to new fiction. Ashley Kalagian-Blunt’s psychological thriller Dark Mode (April) grabbed my attention when it was doing the publishers’ rounds. Her chilling account of the ways in which the internet permits malicious agents access to our most private selves could not be more on point. From the same publisher in August comes a more literary work by Peter Polites, Western Sydney-based author of Down the Hume and The Pillars. God Forgets About the Poor is a love story to a migrant mother and an epic of migration which tells how a generation “starved for food in Greece and starved for Greece in Australia”.

An early stand-out in an extensive list of titles from Penguin Random House is Ronnie Scott’s Shirley (February), another novel about the relationship between a mother and child, but in this instance a girl growing up in the shadow of a famous TV foodie mother. Shirley comes pitched somewhere between tragedy and comedy, but its eye for our changing society sounds unwaveringly sharp.

Two titles from Picador have me very excited next year (as they should, since I’m their publisher). The first, Ordinary Gods and Monsters, from Fitzroy-based author Chris Womersley, is a tender coming-of-age drama wrapped inside a murder mystery, set in suburban Melbourne during the late 1980s. It’s a novel that reads as if Jasper Jones met Donna Tartt by the Yarra. As for the second, if you thought making a bird the narrator of her beloved debut The Lucky Galah was audacious, prepare yourself for Tracy Sorensen’s The Vitals: a fictional account of the author’s real near-death experience of cancer, as told by her internal organs. It reads like one of Italo Calvino’s luminously weird fables, just with an ocker accent.

Those genre antidotes to pandemic boredom, romance and crime thrillers, remain strong features of the publishing landscape. The smart, tender and riotously funny Toni Jordan arrives in May with Prettier If She Smiled More (Hachette), while Macmillan introduces a charmingly feisty new voice with Karina May, whose Duck a l’Orange For Breakfast arrives in March.

Meanwhile, Kate Morton lands in April with a lush new multigenerational saga – a “love letter to Australia” – called Homecoming (Allen & Unwin).

Suzie Miller was a lawyer before she became a world-bestriding playwright, and the novelistic reimagining of her play Prima Facie (Macmillan) is set to be one of the biggest legal dramas of next year. From the same press comes the most promisingly gruesome psychological thriller of 2023, Naima Brown’s The Shot.

Meanwhile, Ultimo author Zoe Coyle follows her scorching debut Where The Light Gets In with an erotically charged account of feminine revenge in May’s The Dangers of Female Provocation.

Text publishing brings some literary heavyweights to their 2023 list, with a new fiction from Kate Grenville mid-year called Always Greener, alongside a collection of short stories from Nobel Prizewinner J.M. Coetzee entitled The Pole and Other Stories. The firm’s new translation of Mexican author Fernanda Melchior (This is Not Miami, April) brings one of the rising stars of Latin American fiction to our shores.

I’m a huge fan of Dominic Smith, and not just for his breakout novel The Last Painting of Sara de Vos. His new fiction, set in a nearly-abandoned Italian village and featuring long-buried family secrets, is called Return to Valetto (Allen & Unwin). From the same publisher, and from the pen of much-loved film maven turned author Shirley Barrett, comes Mrs Hopkins – sadly published posthumously as Barrett died of cancer earlier this year.

I’m not including YA fiction in this list but Tegan Bennett Daylight is such a fine author for adults I feel moved to mention her first foray into the genre with Royals (Simon & Schuster) in June. The publisher’s elevator pitch? Lord of the Flies reimagined for Gen Z. I’m sold on the premise alone.

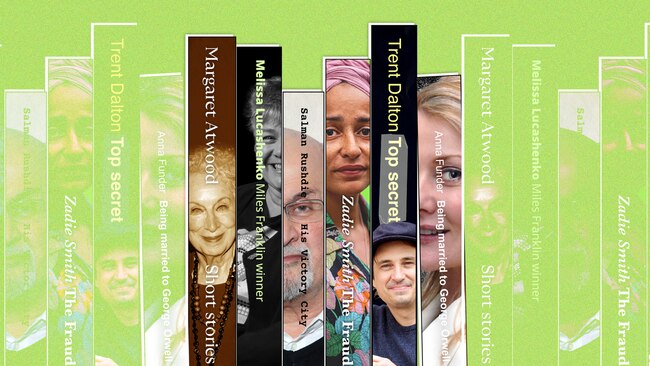

From the irrepressible typewriter of my dear colleague at The Australian Trent Dalton, a new novel. No publication date or title as yet, but doubtless it will be another huge title for HarperCollins. The man doesn’t publish by halves.

Finally, 2023 looks to be a banner year for Indigenous fiction. Next year sees titles that suggest, once again, that First Nations literature is the most vibrant, engaged and necessary writing taking place in Australia today.

From UQP come new novels from Melissa Luckashenko and Tony Birch. The former, Edenglassie (October) is a big-canvas fiction in which the Miles Franklin Award winning-author tells two Indigenous stories set five generations apart: set in early colonial Brisbane, and the city in the present day. Birch’s novel, Women and Children (November) is also concerned with two generations of an Indigenous family who must deal with the long aftermath of a terrible act of violence.

Then there is Alexis Wright, whose Praiseworthy arrives in April. Wright’s epic fable of a small northern town and its cast of extraordinary characters will appear, like the others above, during the year when a referendum on an Indigenous voice to parliament will take place. Never has there been a more important time to take heed of what they have to say.

Doubtless a thousand listicles will bloom online in the coming weeks, celebrating overseas fiction in 2023. But it’s still worth briefly noting some of the big names heading down the chute.

The most surprising, perhaps – since the author has had some unplanned downtime in recent months – is Salman Rushdie. His Victory City (PRH) is described as a “magical realist feminist tale” and takes the form of a faux-translation of an ancient Indian epic – a set up and a milieu that sounds very much in the author’s wheelhouse.

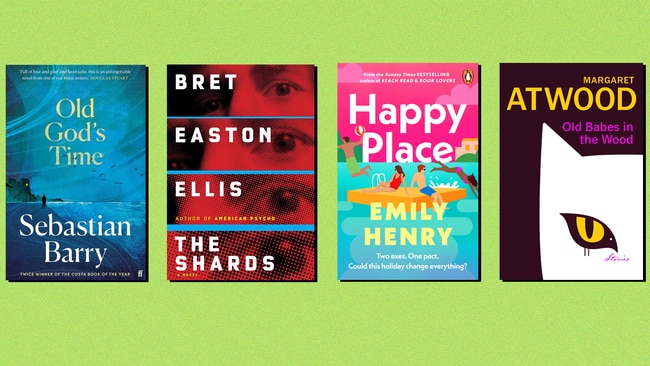

The effortless storytelling charm and mellifluous prose of Irish author Sebastian Barry returns in the shape of Old God’s Time (A&U, March) – a novel of contemporary Ireland, haunted by collective guilt and individual trauma – while from the same house comes a new novel by that poéte maudit of Los Angeles and late capitalism (American branch), Brett Easton Ellis. The Shards comes out in February and I’m already reading my proof copy with appalled fascination. And if you need an antidote to Ellis’s studied anomie, the beloved romcom writer Emily Henry will have her new one, Happy Place (PRH), out in April.

The Penguin Random House juggernaut is set to bring some big contemporary authors in 2023 besides Rushdie, starting with a deeply personal short story collection from Margaret Atwood, one bearing the delectable title of Old Babes in the Wood.

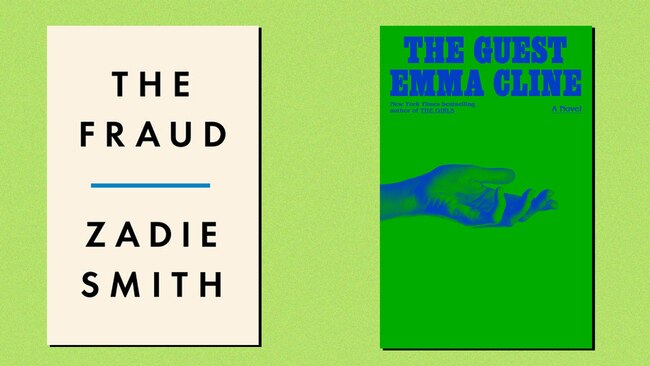

Readers can also look forward to a new fiction by Zadie Smith called The Fraud, a tragicomic historical novel set in London; Emma Cline’s much-awaited follow-up to The Girls, entitled The Guest; and a new one from the brilliant Lauren Groff, author of last year’s must-read The Matrix. This one is called The Vaster Wilds and is set in the 1600s, exploring early North American captivity narratives, which makes it far more contemporary than her last outing, which mostly took place in a 12th century nunnery.

Let us begin non-fiction as we concluded the local fictions section:

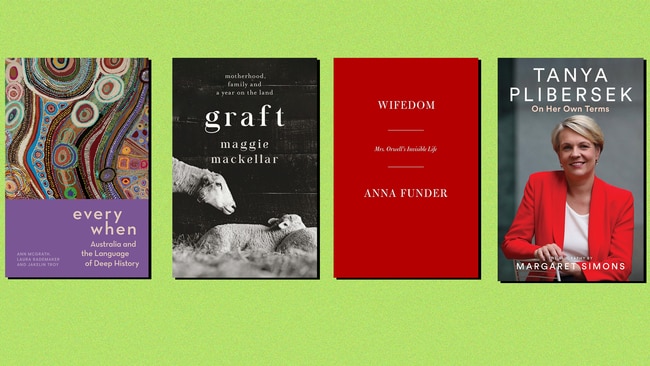

Everywhen: Australia and the Language of Deep History, edited by Ann McGrath, Laura Rademaker and Jakelin Troy Tro (New South Wales ) is animated by some radical ideas. It’s a collection of essays about “diverse ways of conceiving, knowing, and narrating time and deep history” in the Australian context. Its broader argument? That “Indigenous embodied practices for knowing, narrating, and re-enacting the past in the present blur the distinctions of linear time, making all history now” – a notion with profound implications for how we think about land and sovereignty.

In July, from the same the same publisher, comes Sam Twyford-Moore’s intriguing account of Australians in Hollywood. First We Take Los Angeles: A History of Australians in Hollywood furnishes portraits of everyone from Errol Flynn to David Gulpilil, Peter Weir to Gillian Armstrong, in an attempt to show how our national sense of self and collective was shaped and reflected by that dream factory on the other side of the Pacific.

From Monash University Press comes a new book by one of the country’s sharpest cultural critics. Richard King’s Here Be Monsters: Technologyscience, Capitalism and Human Nature asks how we might embrace an increasingly technological future without losing our basic humanity. We need, he suggests, to develop a properly critical orientation to new technologies if we are to avoid becoming trapped in those algorithms that increasingly shape our world.

If that prospect terrifies you, may I suggest surrendering to the old rhythms of the agricultural year? In Graft: Field Notes on Being (PRH), Maggie Mackellar, one of our most eloquent and thoughtful poets of the rural round, describes the cycle of work and life on the sheep farm on Tasmania’s east coast which she shares with her partner. Life, death, love, beauty and nature: you can find it all in the course of a single lambing season.

Another big title from Penguin Random House is Anna Funder’s Wifedom, about Eileen Maud Blair, wife to George Orwell the great English author. Employing recently discovered letters from Eileen to her close friend, Funder recreates the Orwells’ private life and asks the question: what does it take to be a writer and what it is to be a wife? It’s a “breathtakingly intimate view of one of the most important literary marriages of the 20th century”, promises the publisher. And “a book that speaks to our present moment as much as it illuminates the past”.

Speaking of women in the present, Melbourne’s Black Inc. opens its 2023 list with a biography of Tanya Plibersek by Walkley award-winning journalist Margaret Simons. Drawing on exclusive interviews with Plibersek, her political contemporaries, family and friends, Tanya Plibersek (April) traces the story of the longest-serving woman in Australian federal politics.

From the same firm in the month following comes another necessary book. Alan Finkel’s Powering Up is a blueprint for decarbonisation by Australia’s former chief scientist, from “petrostate” to “electrostate”. This is, Finkel writes, the biggest economic challenge humanity has ever faced.

I’ve always been a huge fan of Marele Day as a crime-writer, but next year the author detours into non-fiction. Reckless (Ultimo) tells the story of a shipwreck adventure the young Day experienced years ago, during which she met and befriended an international fugitive travelling under a pseudonym.

This new book tells the story of their reconnection, after three decades of corresponding, when Day visits France: an encounter which will uncover the truth about her friend, a man known as “the hijacker with heart” and “brother to the poor”, who is connected to the disappearance of eight million francs and a secret dossier which made global headlines. A story so wild, in other words, that Day couldn’t make it up.

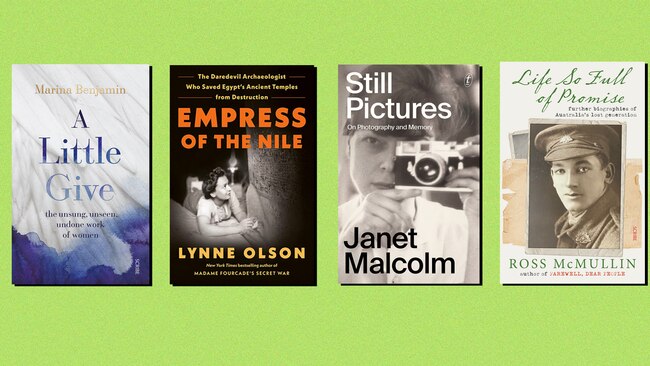

One essay collection captured my attention and wouldn’t let go. A Little Give: the unsung, unseen, undone work of women by Marina Benjamin (Scribe, February) is one of those books that reorients ourt sense of how society is ordered. Its interlinked pieces take another look at those human tasks traditionally designated as “women’s work” and recasts them as profound and essential acts of labour and love. Also from Scribe, two fascinating and very different works of life-writing. The first, Empress of the Nile, by Lynne Olsen, tells the story of Christiane Desroches-Noblecourt, “the feisty French archaeologist who led the international effort to save ancient Egyptian temples from the floodwaters of the Aswan Dam”.

The other, by historian and biographer Ross McMullin – a companion volume to his Farewell, My People, winner of the PM’s award for History – is Life So Full of Promise, a new multi-biography exploring Australia’s lost generation of World War I.

Speaking of promise-filled lives, Hardie Grant will be releasing a biography of a remarkable Australian in April. Jimmy Little: A Yorta Yorta Man is the story of the iconic Indigenous singer/songwriter, as told by his daughter, Frances Peters-Little.

The always brilliant Janet Malcolm is celebrated with a posthumous memoir out from Text in January. Still Pictures: On Photography and Memory is a work of life-writing that uses photography – an artform she wrote about with more insight and philosophical elan than almost anyone else – to turn the lens upon her own experience. Meanwhile, in Flooded Canyon (Upswell, late 2023), Australian cultural critic and filmmaker Ross Gibson uses poetic forms to notate the changing space of Sydney Harbour – a body of water he has been watching with love and fascination for decades.

HarperCollins has a new one out next year from the always-edifying Simon Winchester. Knowing What We Know (William Collins) is a “global narrative history of how civilizations have accumulated knowledge.” It sounds like a hymn of praise to the eccentric yet immensely valuable work of those who have compiled encyclopedias, almanacs, dictionaries and even Wiki-entries. HarperCollins will also publish a new biography of Gough Whitlam by The Australian’s Troy Bramston. And with one last nod to the centrality of Indigenous narratives in the coming year, Black Inc.’s next Quarterly Essay will be authored by Megan Davis, Professor of Constitutional Law at UNSW and a former chair of the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues. In the 90th number of the journal, the woman who read out the Uluru Statement from the Heart for the first time at Uluru in May 2017, makes a cogent and impassioned case for a First Nations Voice to Parliament. Reading doesn’t get more necessary than this.