How teenage trauma can stay with you

"To be predictable is my worst nightmare," Daniel Johns told us.

"To be predictable is my worst nightmare," Daniel Johns told us.

“I just want to be the best songwriter in the world that’s ever happened, and I’m not scared of saying that,” says Daniel Johns.

Johns, who just turned 43, has spent almost 30 years in the fierce glare of the spotlight, as a teenage rockstar with Silverchair.

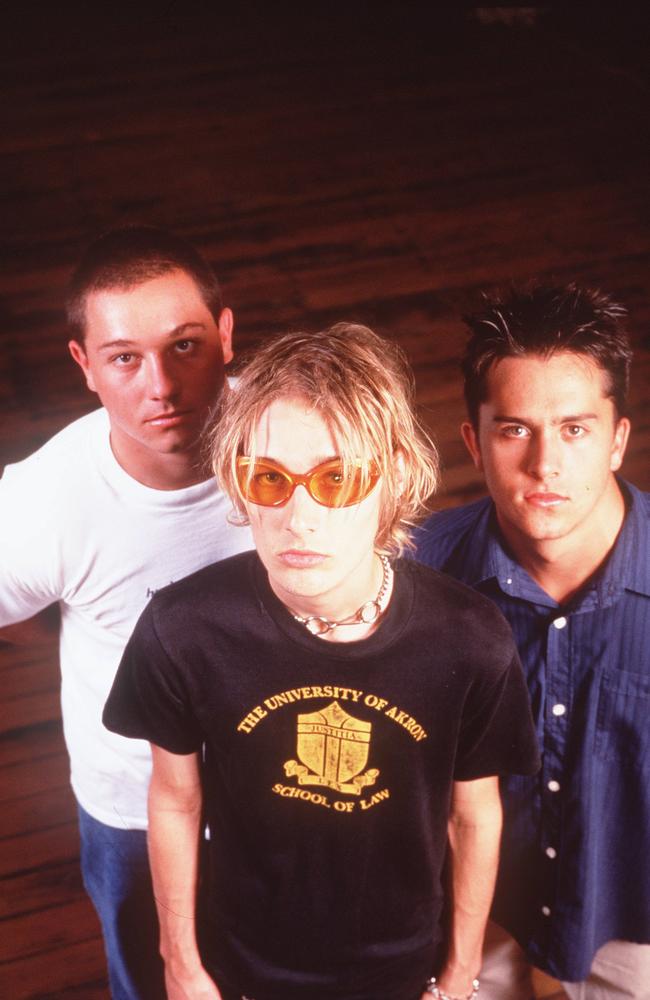

All three members of the Silverchair fold: Johns, drummer Ben Gillies, and bassist Chris Joannuo, were just 15 when the band released their debut album, Frogstomp.

The record was an instant hit: debuting atop the Australia charts, it reached the Top Ten in the US (where it was later certified double-platinum), and sold millions worldwide. Before the age of 16, Silverchair had toured the US alongside Red Hot Chilli Peppers and the Ramones, and performed atop New York City’s Radio City Music Hall for the MTV Music Video Awards.

For a young Daniel Johns, the fame was corrosive. It contorted his body like a funhouse mirror, resulting in the eating disorder anorexia nervosa, which he chronicled in the 1995 single Ana’s Song (Open Fire). His mind distorted in dangerously self-destructive ways that he’s still coming to terms with. Although he was bold enough at the time to become one of the few famous Australian males willing to discuss his mental struggles publicly.

For most of his life, Johns’ image has been bought and sold by entities beyond his control; his story told time and again with little agency on his part.

“There’s been a very disengaged and irrelevant interpretation of what’s happened in my life; I’ve let the powers-that-be tell my narrative,” says Johns.

This sense of being misunderstood is what led to Who Is Daniel Johns? A five-part documentary podcast published on Spotify last year. Produced by journalists Kaitlyn Sawrey and Frank Lopez — it uncharted the Joe Rogan Experience in Australia and Canada.

“I tell everyone I beat Joe Rogan,” says Johns. “I just like people thinking that, because you know how Joe Rogan got, like, $240 million? I didn’t even get close to that. I think I got like $100,000 – which paid for the leak in my kitchen roof. I didn’t get that sweet Spotify money.”

Most importantly, the podcast allowed Johns to “speak the truth without throwing anyone under the bus.” Through it, he was able to tell his story “without feeling like I was a rat”.

“Believe me, I could have said some shit that would have fucked some people up. But I just thought I’d take the high road. All I want to do is tell the truth, without the bad bits – because the bad bits you can hear in the music,” he says.

Johns’ father Greg is an ardent music fan who ran a fruit stall in Newcastle, while his mum Julie raised the family. The eldest of three children, Daniel vividly recalls the first guitar-based album that made him want to be in a band: Deep Purple In Rock. When he got his first electric guitar as a child, the first riff he learnt to play by ear was Money For Nothing by Dire Straits.

“I remember my dad came into the bedroom and was like, ‘How did you learn that?’” he says. “I saw the smile on my dad’s face and it made me want to play guitar even more. And then my mum was kind of impressed, and that was the beginning of writing Frogstomp: ‘Shit, my parents think I’m kind of all right!’ ” They weren’t the only ones. The three Silverchair teenagers wrote, recorded and toured in a constant cycle for several years while continuing their high school studies.

Johns bought this house in 2000 after coming off tour for the band’s third album Neon Ballroom. It’s located on a quiet street in the same coastal suburb where he grew up, but he now has a much better view. From his vantage point cut into a cliff, in a huge house containing a squash court with viewing platform – although the singer doesn’t play – Johns holed himself up for much of 2000, rarely leaving his bunker, opting for isolation two decades before the rest of us got a taste of it.

It was here that he learnt to play the piano on which he wrote Silverchair’s 2002 masterpiece Diorama. He wrote the lead single The Greatest View while looking out the front window down the hill, toward his parents’ house. I’m watching you watch over me / And I’ve got the greatest view from here, he sang in its chorus.

Asked about what his parents mean to him, Johns takes the longest pause during six hours of conversation and frivolity. “I know without my family’s support, I would have gone heavily off the rails,” he says eventually.

“It was their belief in me that made me not do that. There’s been times where I’ve been that close,” he says, holding up his index finger and thumb to indicate a tiny gap. “I could have gone really bad. I’ve been to a lot of institutions; I was suicidal when I was younger. I just couldn’t deal with it, and they just kept believing in me and believing in me.

“My brother, my sister – my family’s so fuckin’ tight. I’m unbelievably grateful, because some of the shit that I’ve done, most people would have gone, ‘You’re a fucking disaster’,” he says, laughing.

“I’ve put them through hell, and they’ve never backed away. They were always supportive. That’s fucking rare. I’ve had friends back away, but my family’s always been like, ‘No, we’ve got you – you can do it.’”

Johns became increasingly reclusive following the release of Silverchair’s second album, 1997’s Freak Show. Cooped up at home, clinically depressed, feeling the pressures of media intrusions, stalkers, fans hassling his family and hand-delivering suicide notes, and critics that would spray paint graffiti on his front fence if he didn’t leave the house. It was under these conditions that his anorexia manifested. Whilst Gillies and Joannou were able to live reasonably normal lives largely free from scrutiny.

On his podcast, Johns revealed that that the only aspect of his life he felt he could control was his decision to eat. “That’s eating disorder 101."

He confined himself to his bedroom, waiting for everyone to go to bed, when he would take his dog for a walk "at 2am for like, three hours because I was anorexic so I was trying to lose weight,” he said.

Silverchair has been on “indefinite hiatus” since May 2011, when the musicians noted in a statement that “we stand by the same rules now as we did back then… if the band stops being fun and if it’s no longer fulfilling creatively, then we need to stop”.

Friends since they were seven, the three former bandmates don’t talk much anymore; Johns likens the relationship nowadays to a divorce. “We’ve never really healed, but I don’t dislike them, and they don’t dislike me, I don’t think,” he said on the podcast. “But it’s just really awkward, and it’s hard to mend that bridge.”

Structurally speaking, little has changed in this house since Johns bought it at age 21. Sonically, though, this sprawling living room has been filled with his life’s work as an adult songwriter. The black Yamaha piano still sits in the front corner, near the entrance and behind the dense green hedge that shields him from prying eyes. A drum kit, guitars, bass and keyboards are all within easy reach.

The classic Nas hip-hop album Illmatic is playing softly on the stereo on my arrival; small photos of Tom Waits, Keith Richards and Jimi Hendrix hang above his television, while a large portrait of the wired eyes of Ian Curtis – the Joy Division singer who died at age 23 – is stored downstairs, the image deemed too creepy and morbid for Johns’ bedroom.

Since Silverchair’s final album Young Modern was released in 2007, and the band played its final shows together in 2010, his musical output has been slim: after releasing a solo album rooted in R & B and electronic music in 2015, he arranged the soundtrack for the children’s animated series Beat Bugs in 2016, and issued a collaborative album with Empire of the Sun frontman Luke Steele in 2018 under the moniker Dreams.

None of these projects set the world on fire, commercially speaking. Johns hasn’t had a hit song in 15 years, since Straight Lines in 2007. Performances have been few and far between, too. His last live appearance was at Laneway Festival in 2019, where he emerged from a coffin during a set by friend Chris Emerson – aka Sydney electronic musician What So Not – to play a scorching version of Freak.

Johns’ new album, FutureNever, is his most diverse and creatively expansive work to date. The 12 tracks are by turns surprising, dramatic, cinematic and more than a little show-offy. The arrangements touch on pop, rock, classical and electronic music, while his vocal performances are stunning.

It almost never saw the light of day.

After his debut solo album Talk, he felt spent. “I really, really tried so hard to prove myself outside of being ‘the guy from Silverchair’,” he says from his couch. “It wasn’t a failure, but I didn’t feel like it had any support. Sometimes I get sentimental when I’m sitting at home by myself at four in the morning and I go, ‘I’m gonna put on Talk.’ I don’t have any moment where I go, ‘Fuck, I shouldn’t have done that’ – and that’s one of the first records in my whole career where I still love it.”

Given the close-knit ties between himself and his two siblings, it’s fitting that it was his younger brother Heath who talked him into releasing new work. Heath has stuck like glue to Daniel all the way through. At the Silverchair frontman’s most challenging moments – when he was bed-bound and in debilitating pain from a mysterious illness that also crippled the band’s ability to tour Diorama – it was Heath who stayed up late with him, watching music videos on Channel V together in their parents’

In 2016 Johns was ready to retire from public view, having taken a significant creative risk that didn’t really pay off. “After Talk, I was like, ‘I don’t want to do music anymore, it’s just not worth it. I put too much effort in and I get nothing in return.’ I just felt like it was a waste of time. I’ve got a house, I’ve got a girl, I’ve got a dog, I’ve got a car… I’ve got a squash court,” he says, laughing. “I don’t really need anything. I’m just going to paint. ”

Johns has a private online folder of unreleased music and while sifting through it one day, Heath – who is the managing director of record label BMG Australia – had a revelation. The songwriter’s mindset at the time was that he wrote music anyway, every day; he didn’t need other people to hear it. “But Heath was the one that was like, ‘No, dude – this is your best shit’,” says Johns. “I had no idea, ’cause I was totally checked out. I thought it was just nothing.” Now he agrees with Heath. “I love this record. I honestly think it’s the best thing I’ve ever done.”

Nobody knows whether fans will flock to his new album like they did with Frogstomp or scratch their heads and edge away, as most did with Talk. “I don’t give a fuck what people think – I know it’s good,” says Johns.

“Sometimes I find the general public so stupid – but most of the time, I think the general public is way smarter than record companies give them credit for.

"Most people who are interested in art and music, they want to be challenged; they don’t just want meat and potatoes. Sometimes you just want a side of seaweed with sesame seeds and ponzu sauce; something to intrigue your palate.”

Then he cracks up, breaking the spell on an otherwise serious discussion about the meeting between art and commerce. “Shittest metaphor ever, but you know what I mean?” he says, laughing. “I was trying to be funny. I really think people underestimate people’s appetite to be at the very least intrigued. To be predictable is my worst nightmare.”

“I feel like I’m being very vain, and this is why I hate doing interviews, because when I tell the truth, it feels like I’m arrogant, and I’m not,” he says. “I’m actually very insecure. I still think I’m a bit crap. I still think I’m not at the level I want to be.”

“Most people would just rest on their laurels. I don’t have laurels, and I don’t rest.”

The full, original version of this feature appeared in The Weekend Australian Magazine and was written by Andrew McMillen.

If you or someone you know needs help with an eating disorder, contact the Butterfly foundation on 1800 ED HOPE (1800 33 4673).