Gallipoli landing: confusion and courage reigned

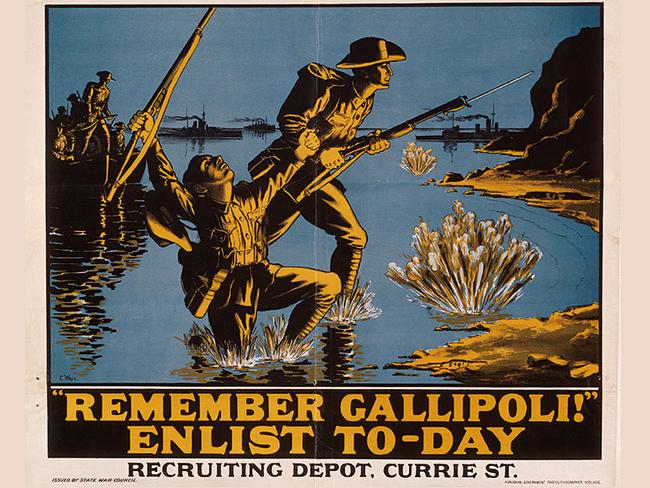

Hostile terrain, inexperienced men, poor planning ... at the Gallipoli landing, confusion – and courage – reigned supreme.

Before dawn on April 25, 1915, Tom Whyte hauled on an oar as the lifeboat packed with Australian soldiers headed towards the beach at the place the Turks called Ari Burnu. A champion rower from Hyde Park in South Australia, Whyte had volunteered to help bring his boat onto the tight curve of coastline that would soon be known to his nation as Anzac Cove.

On the headland above, 16-year-old Adil Sahin was in a line of Ottoman Turkish soldiers peering anxiously through the darkness searching for the source of noises on the beach below. He made out the shapes of boats pulling towards the shore and soldiers clambering out. Private Sahin and his comrades had no idea who the invaders were – perhaps their longtime enemies, the Greeks, or the British – but the boy soldiers were soon ordered to open fire. The Turks saw some of the attackers go down, but they did not know if they’d been hit or dived for cover.

The men below were Australians, the first members of the Anzac force to land. In the first boats were three mates: Whyte, who had spent the evening before writing a letter to be delivered to his fiancee, Eileen, in the event of his death; Arthur Blackburn, who went on to receive the Victoria Cross for heroism in France; and Phil Robin, who died at Gallipoli later on the day of the landing. The men were scouts assigned to fight their way as far inland as possible before the Turks could counterattack.

Blackburn later said the rowers were the most exposed men in the boat and Whyte was brave to volunteer. Indeed, Whyte did not get to leap ashore with his mates. He was shot in the stomach as they landed and died on a hospital ship.

Historian Charles Bean wrote that Blackburn and Robin did get further inland than anyone else in the force. Like the Turkish soldiers above them, the Aussie soldiers knew little of the enemy they’d been pitted against in the impact zone of what was to become a brutal and costly clash of empires.

According to Kevin Fewster, Vecihi Basarin and Hatice Hurmuz Basarin in Gallipoli, The Turkish Story, Adil Sahin survived the war, but of 33 men recruited from his village, only two lived to come home with him.

READ MORE: The Great War, Part One: The Road to Gallipoli

The Gallipoli campaign had begun two months earlier as Winston Churchill, then First Sea Lord, looked for a way to break the deadlock on the Western Front by opening a sea route through the Dardanelles to send supplies to Russia.

When British and French battleships were sunk by Turkish minefields and a German submarine, the decision was made to land troops to overwhelm coastal defences so the minefields could be cleared. Greek generals advised the Allies 150,000 men would be needed to take Gallipoli; British commanders, who seriously underestimated the Turks’ willingness to fight, thought it could be done with 70,000. They thought the fading Ottoman Empire, “the sick man of Europe”, would quickly fold. That was the biggest miscalculation of all and the Allied campaign was dogged in its early stages by inadequate planning, poor maps and a lack of valuable intelligence. As it turned out, losses on both sides were terrible but the highest price was paid by the Turks.

The Australian War Memorial’s chief historian, Ashley Ekins, strongly rejects what has become a truism about the landings – that the Anzacs got into trouble because they were landed in the wrong place. Had the troops landed on the wide and open stretch of beach to the south they would have been slaughtered, he says. Because that was an obvious landing place, the Turks had heavily defended it with artillery and barbed wire. “It would have been like Omaha Beach in the Normandy landings,” Ekins says. That was where US troops invading France found German coastal defences largely undamaged; many soldiers were shot down as they left their landing craft.

At Gallipoli, landing so many men on a hostile shore in the dark was a complex operation, and there was considerable confusion on the day. “It was really a stab in the dark in more ways than one,” says Ekins.

The first troops to land were a screening force of 1500 men who pushed inland. The men were to go as hard and as far as they could to get to the feature that became known as the third ridge. It is another myth that the men actually overran the Turks on that ridge, Ekins says. “Most of them didn’t even get there.” These men were to swing to the left and the right to capture Turkish strongpoints and hold the high ground until the next wave could come up and reinforce them. “None of that was feasible,” says Ekins. “They simply did not have the numbers to carry that out.”

Even if whole divisions had been landed they would have been strung out thinly across an enormous area. At Anzac Cove, the land rises steeply just a short distance inland; from the Allied side of the battlefield the ground, rent with cutaways, washaways and steep ridges, is hard to climb. “It’s all very well to say you can capture the high ground but then you’ve got to supply your troops with weapons, with ammunition, with reinforcements, with water,” says Ekins. Since everything had to be carried by hand, “resupplying those high posts – if you’d actually captured them – would have been impossible.”

From the Turkish side, the battlefield was approached through gently rolling farmland that was easy for the defenders to get to.

After they landed, the troops were bunched up and confused in the dark and their landings were out of sequence. Units were intermingled, and officers had to find their men.

False claims and misinformation emerged as commanders tried to explain why the landing force had failed to reach any of its objectives by the end of the first day. They were meant to be, by then, about 10km inland on top of a feature called Mal Tepe. “They had not got within miles of any major objective,” says Ekins. “They were to have captured the heights as well but they were nowhere near them.” The beachhead was about 2.5km long and its deepest point was about a kilometre inland. “And that was where they remained for eight months, fundamentally.”

In fact, the bulk of the first wave of Anzacs got ashore fairly easily; the heaviest fighting that day took place on the heights with some key positions changing hands several times.

The key strategic hill known as Baby 700, a pivotal position throughout the campaign, was won and lost five times. Lone Pine, scene of bloody battles months later, was said to have changed hands at least three times. “The Turks would grab it and hold it and then the Australians would charge and they’d get it briefly,” says Ekins. But at the end of the first day all the important hills were still in Turkish hands, even those the Australians had managed to wrest away temporarily, only to be driven back.

Then came two weeks of heavy fighting as the Anzacs battled to consolidate and improve their positions and to take those high points. That included fierce battles to try to take Baby 700, which stood at the apex of a rough triangle formed by the Anzac positions. “They realised that this was the single hill that looked right into the Anzac positions,” says Ekins. It was the hill from which Major General William Bridges, commanding the First Australian Division, was mortally wounded and the famed Simpson, who carried wounded soldiers to safety on his donkey, was killed.

As the first day drew on, the Anzac commanders became increasingly alarmed. They were no longer in touch with their men, says Ekins. They were holding a ragged line. They didn’t know what their dispositions were, in what strength they were or how many of them were secure. “They were getting reports that the men were melting away under shell fire during the day and the line wasn’t properly held,” says Ekins. And then, to add to the misery, it began to rain.

“All you’ve got to do is dig, dig, dig until you’re safe”

Bridges and Lieutenant General William Birdwood, commanding the Anzac Corps, told the overall commander, British General Ian Hamilton, that they should evacuate the entire Anzac force. “That was a very unsteady sign,” says Ekins.

One of the best Allied officers, Harold “Hooky” Walker, argued vehemently that that was insane. “He was right,” says Ekins. To try to withdraw a force which was scattered around a perimeter in the dark in unknown positions and in close contact with the enemy would have undoubtedly turned into a rout. Interestingly, Walker had earlier opposed the whole invasion plan because he believed it would not work. But he also was aware that simply ordering the troops to leave now could only lead to disaster.

“Hamilton, for once on that whole day, showed a very firm and steady hand,” says Ekins. He asked his naval commanders if they had the ships to get the Anzac force off the beaches intact. They told him such a withdrawal would be a long, slow and very difficult process. “Hamilton fired back a signal saying evacuation is out of the question and you’ve got through the difficult business,” says Ekins. “All you’ve got to do is dig, dig, dig until you’re safe.”

That’s what they did. The Anzacs dug trenches and tunnels for months and they never stopped until their final evacuation.

On the day of the landing, large and small groups of Anzacs made it some distance inland before being stopped by Turkish troops rushing to repel the invasion. Some were able to withdraw, some fought and died where they stood and others simply vanished. In some cases the war was over before details emerged of heroic fights to the finish by isolated groups.

Over the days that followed the landing, the Anzac forces made desperate attempts to break out of the beachhead with similar results. On May 2, the 16th Battalion, made up of men from South and Western Australia, gained a foothold on a ridge ahead of the feature known as Pope’s Hill. Surrounded, they dug shallow trenches and held on against repeated counterattacks until they were overwhelmed.

Private Martin Troy survived to describe much later what happened to his unit. “We took the ridge but lost heavily. We dug in as well as we could but the Turks managed to press back our left flank and then got round behind us.” The main allied force made heroic efforts to fight their way through to the beleaguered unit but was repeatedly beaten back.

During a Turkish attack early on May 4, Troy was blasted unconscious by a hand grenade. When he regained consciousness, all of the Australians around him were dead or wounded and Turkish soldiers were finishing off the survivors. “At about 8am I was knocked senseless by a bomb,” Troy recalled in a report he filed after the war. “On regaining consciousness I found myself surrounded by dead and wounded.”

Badly hurt, the young soldier crawled away in a bid to escape, but the area was swarming with Turkish soldiers. He was found by a German officer serving as an adviser to the Turkish forces. Troy’s uniform had been torn apart by the blast and the German spotted a religious medallion on his chest next to his ID dog tags declaring that he was R/C. The German asked in perfect English if he was, indeed, a Catholic. Troy said he was.

For three days the enemy officer kept the wounded Australian hidden on the battlefield. Then he came to tell him he would be made a prisoner of war so that he could get medical attention. Troy spent the rest of the war in a Turkish POW camp.

As both sides expanded their trenches, the fighting quickly became mired in the Western Front-style siege warfare that Gallipoli was intended to circumvent. The Turks held all of the high ground and overlooked the Anzacs from all sides; they had the ability to dig in, knowledge of the ground and the experience of hardened military men. “The Australians were amateurs in the extreme,” says Ekins. “The New Zealanders as well. There were a few with a bit of Boer War experience, or some soldiering perhaps with the British army.” But many of the Turks were men who had fought in several wars. Their commanders knew combat and they knew campaigning.

In those days, news travelled slowly. It was some days before Eileen Chapman learnt of her fiance’s death.

“My dear sweetheart, I thought of writing this in case I went under suddenly. Not that at present I have any thought of not seeing you again but in case of accidents,” Whyte wrote.

“But the thought that hurts worst of all is of you and your sorrow. Just think of me as non-existent in spirit, blotted out completely ... It would soften the last thoughts if I knew you would be really happy again ... Goodbye my love, may you get all the happiness you deserve, that will be my last wish.”

-

Gallipoli: the cold, hard facts

The eight-month-long Gallipoli campaign involved a total of about one million men from both sides. Between one-third and one-half of them became casualties. Precise figures are unavailable for some nations and there are discrepancies between data from various statistical sources.

About 469,000 British Empire soldiers served in the campaign (328,000 combatants and 141,000 non-combatants). About 120,000 became casualties, of whom more than 34,000 died. The maximum British Empire strength at any time in the theatre was 128,000 personnel (85,000 combatants and 43,000 non-combatants). About 79,000 French soldiers also served in the campaign.

About 500,000 Turkish soldiers are believed to have served on Gallipoli and their casualties are estimated at between 250,000 and 300,000, of whom (according to Turkish official sources) almost 87,000 died.

Between 50,000 and 60,000 Australians served on Gallipoli and 8709 were killed in action or died of wounds or disease. In addition, 19,441 Australians were wounded (including those wounded more than once) and 70 Australians were captured; 63,969 Australian cases of sickness were reported in the campaign.

Of the 8556 New Zealanders who served in the campaign, 2721 died and 4752 were wounded (including those wounded more than once). Total Anzac casualties amounted to 11,430 dead and 24,193 wounded.

A high proportion of those recorded as dead on both sides were missing: 3268 Australians and 456 New Zealanders have no known graves; and 960 Australians and 252 New Zealanders were buried at sea. Of the total of 9829 French dead, 6091 were listed as missing.