Undersized, scrappy underdog defeats his athletic superiors – but his pathological obstinance off the field ruined it all

Pete Rose was as big a star as an athlete could be but broke a cardinal rule of baseball – steer clear of gamblers.

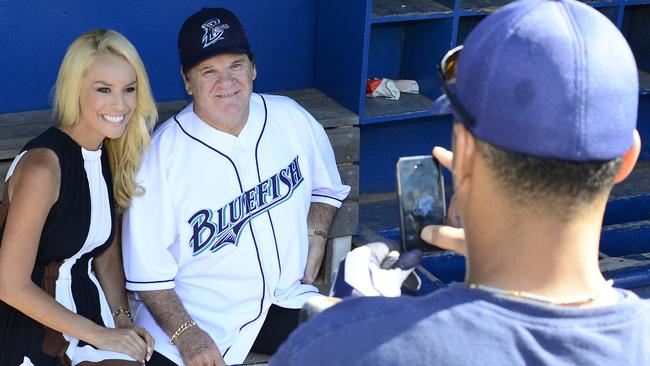

Pete Rose never goes away. He’s still here in body, of course, now 82, surely this very second signing everything in sight at a memorabilia show in a medium-size convention hall somewhere across America, telling whoever’s willing to pay him a few bucks how Major League Baseball should reverse his lifetime ban from the sport, laid down 35 years ago for gambling on his own team.

Rose reapplies to the commissioner every few years, gets rebuffed, and then just dusts himself off and tries again.

As a player, Pete Rose was irresistible. When you close your eyes and think of Willie Mays, you see him gracefully gliding through centre field; Derek Jeter, a deep throw from shortstop; Ken Griffey Jr, his perfect, sweeping swing. But Pete Rose? You think of him sprinting toward an open base and leaping for it, arms and legs splayed, as if he were a man on fire diving for water, as if being safe were the only thing that had ever mattered in the world.

“He runs like a scalded dog,” one of his early managers said. “He’s got more stomach than a parachute jumper.”

“Charlie Hustle”, the nickname Keith O’Brien has made the title of his biography of Rose, was actually given to him by Mickey Mantle and Whitey Ford, who were making fun of how ostensibly, even showily, hard the guy worked, how little seemed to come naturally to him. Because of that quality, however, Rose will always loom large as an avatar for a very specific style of sports superstar, the undersized, scrappy almost-always-white underdog who defeats his athletic superiors through relentless intensity – an ethos to himself.

I see Pete Rose every time I watch a Little League dad scream at his kid to sprint to first base on a walk, every time someone says they just don’t make baseball players like they used to. Rose is forever a one-man baseball culture war.

But he’s also a man, made of flesh and blood and anxieties and regrets like the rest of us, and I’m not sure there’s ever been a book that does a better job of sketching out that man than Keith O’Brien’s. The author, a journalist, grew up in Cincinnati during the peak of Rose’s career, revering him like everyone else in the city did.

“Charlie Hustle”, a 329-page stem-to-stern bio, chronicles Rose’s upbringing as a working-class Cincinnati kid with a frustrated-athlete father who pushed him to become a boxer. In spirited, affectionate fashion, the author chronicles Rose’s years, in the 1970s, playing for his hometown team and winning championships with Joe Morgan, Johnny Bench, Tony Perez and the Big Red Machine. It is not difficult to understand why that team – by any measure one of the greatest teams in baseball history – was so beloved.

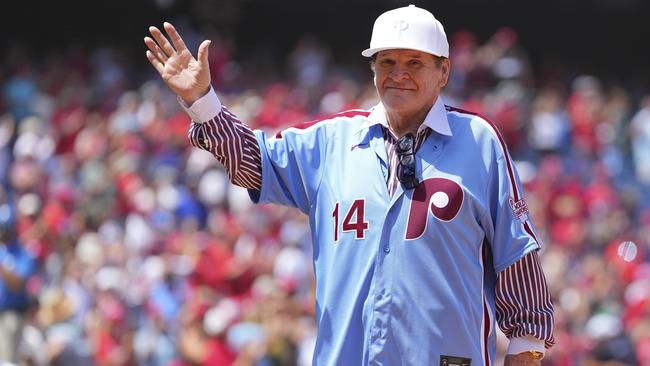

Rose was the public face of the Reds, but when the team started to decline, he went to play for the Phillies and the Expos. In 1984, he returned to Cincinnati to become the last man (so far) to serve as player-manager and to chase Ty Cobb’s record of 4191 hits. In 1985, after Rose passed Cobb’s mark, President Ronald Reagan called to congratulate him, only to have Rose complain about being forced to wait on the line too long.

For a moment, he was bigger than baseball. Then, within a few years, news of the gambling scandal broke and he was forced out of the sport, the only thing he cared about (other than himself): “Pete loves two things, wholeheartedly,” says one of his many paramours. “Pete and baseball.”

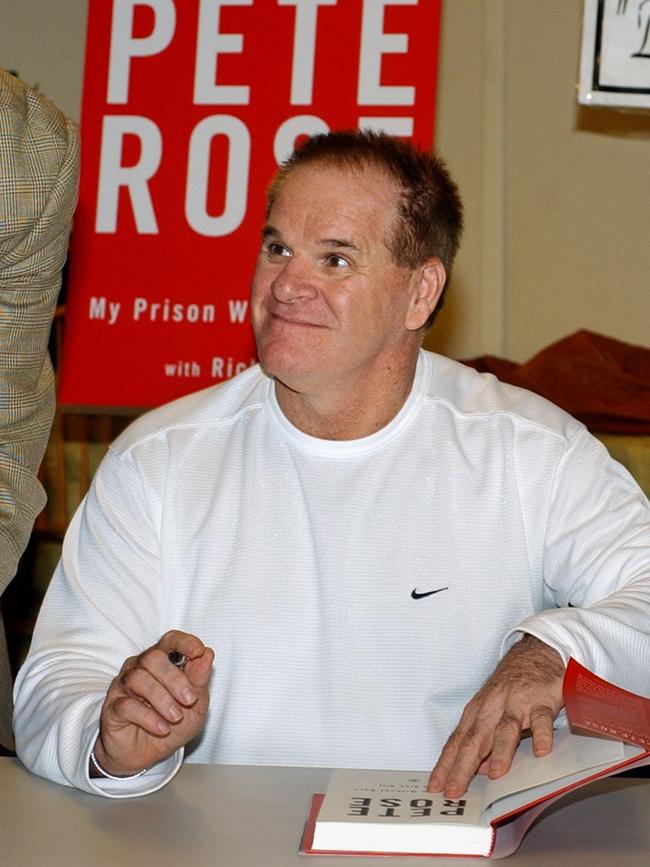

The author approaches his project with an undeniable appreciation of Rose’s appeal and ability to connect with the common fan, but he is not afraid of digging into often unsettling truths. Rose gave 27 hours of interviews to O’Brien, according to the author, but, perhaps inevitably, stopped returning the writer’s calls when he began to get into what his subject calls “the dirty stuff”. And there is plenty of it.

As a hitter, Rose was a bit of a savant, able to retain reams of information on every pitcher in the league, desperate to win every single battle, with a batting eye and measured swing so respected that even umpires questioned themselves if they disagreed with him on a call.

But the same qualities that drove the player to be so unremitting on the field carried over to an almost pathological obstinance off the field.

As Rose earned more money and gained more power, especially when he returned to Cincinnati, he became almost comically reckless, according to O’Brien. He would carry on multiple extramarital affairs, essentially in the open, including in the company of friendly media members willing to overlook everything, and spent time with so many shady characters – from bookies to cocaine dealers to ’roid heads’ at the infamous Gold’s Gym in Cincinnati – that his teammates kept trying to get them kicked out of the clubhouse. Early on in Rose’s career, he considered himself untouchable, and acted accordingly, one teammate comments.

O’Brien describes him as having an “enduring belief his choices wouldn’t hurt him”. All through O’Brien’s account, Rose’s gambling addiction – there is no other word for it – looms over the action, waiting to take him down. Early in his career, the young Rose would spend most of spring training at the horse track, compiling debts, often finding toadies and lackeys to pay them off.

As he grew richer, everything accelerated. He was renowned for losing thousands of dollars a day gambling on football, horses, basketball, anything, even sports he didn’t know anything about; a policeman who investigated him told O’Brien he was “one of the worst gamblers he had ever met”. As Rose’s gambling spiralled and more established bookies learned he couldn’t be trusted to pay his debts, he was forced to find ever more unsavoury characters to make bets with – many of whom would end up in the crosshairs of the FBI.

Toward the end of the book, O’Brien’s narrative shifts into something almost resembling a thriller, as Rose keeps digging himself bigger holes until he realises the only way out is to bet on the thing he knows and loves best – baseball. He was busted by then-commissioner A. Bartlett Giamatti and John Dowd, an investigator Giamatti had hired, without much difficulty: Pete Rose, in the end, was too out of control to hide much of anything.

But because he was Pete Rose – because he always went all out, always doubled-down – he could never, ever admit this. O’Brien notes just how many opportunities Rose had to simply confess to the obvious truth he had bet on the Reds as a manager and end up with a slap on the wrist. But Rose couldn’t do it, almost out of principle: to relent at the moment he was being accused, to admit weakness, to give in to his detractors, was against his personality both on and off the field.

There has been a movement in recent years to cut Rose slack, largely because of the widespread acceptance of betting in sports these days, particularly from the leagues themselves: O’Brien notes today Rose could play for the Cincinnati Reds and shill for DraftKings fantasy sport on the side. But he still wouldn’t be allowed to bet on baseball. Rose broke a cardinal rule of the sport, the one that remains on the wall of every clubhouse in the majors to this day: don’t bet on baseball. And he did so with aggressive impunity – as if the rules could never apply to him. It was the mindset that made him great on the field. And it’s what ruined him off it.

At the end of O’Brien’s compulsively readable and wholly terrific book, Pete Rose, a tired old man fully estranged from his sport, sits in a new Cincinnati casino, signing one trinket after another, telling old stories from decades ago. Each item at such a signing comes with its own price, but for $35 extra, he will add a specific phrase to the signature: “I’m sorry I bet on baseball.”

This admission, such as it is, came years too late – and also is only a portion of the truth. As he once told assembled reporters years earlier, after being suspended 30 games for bumping into an umpire: “I hate to say it, but I would probably do it again, if the situation came up. It’s just the way I am.”

WALL STREET JOURNAL

Will Leitch is a contributing editor at New York magazine and the author of six books, including the recent novels How Lucky and The Time Has Come

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout