Australia’s football codes alarmed by US brain study

Australia’s football codes are assessing the implications of an alarming US study into the impact of repeated head knocks.

Australia’s football codes and sports medicine specialists are assessing the implications of an alarming US study into the impact of repeated head knocks on the long-term health of athletes.

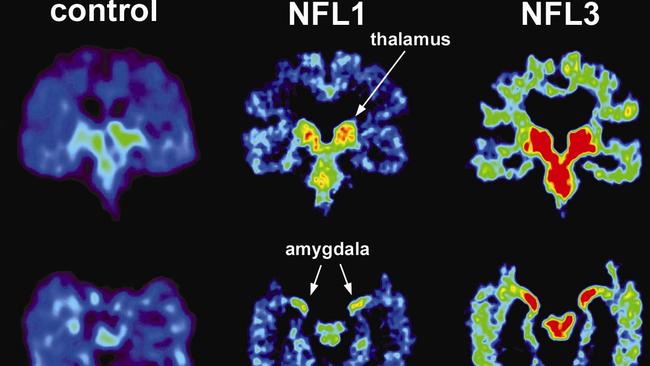

The results of the study, which examined the brains of 202 deceased American football players, found 87 per cent suffered from chronic traumatic encephalo-pathy (CTE). Of the 111 brains from footballers who played in the NFL, only one did not display evidence of the degenerative disease, believed to be caused by repeated blows to the head.

Neuropathologist Dr Ann McKee, whose findings were published yesterday in The Journal of the American Medical Association, said the study should draw an end to debate about the impact of head trauma on NFL players.

“It is no longer debatable whether or not there is a problem in football — there is a problem,” McKee told The New York Times.

But she cautioned there was a selection bias of sorts in the Boston University study and also noted it was difficult to ascertain whether lifestyle habits had an impact on those whose brains were donated.

She said the families of footballers who had donated their brains had done so because their loved ones were displaying symptoms associated with CTE — namely depression, dementia, confusion and memory loss.

Approximately 1300 players have died since the Boston University study run by McKee began examining the donated brains.

But even in the remote chance that none of those players’ brains showed signs of CTE, the prevalence rate would still be about 9 per cent.

As Australian sports medicine specialist Peter Larkins pointed out, regardless of the bias the percentage of players suffering from CTE was alarming.

“That is still a very high CTE rate, far higher than you would see in terms of the people walking around in Sydney or Melbourne today,” Larkins said.

An aspect that most concerned him was the degree to which the study demonstrated that seemingly benign but regular blows — not just those causing concussion — increased the risk of CTE.

Larkins, who has attended the past two International Consensus Conferences on Concussion in Sport, discussed the latest research with some AFL club doctors yesterday.

“There is no doubt it is a topic of discussion. Dr McKee is at the forefront of research and we are looking at that research … and comparing it with footy staff in the AFL and NRL,” he said.

“You don’t have to be concussed to have a head injury or have your brain rattled.”

He stressed it was worth noting there is a distinct difference between American football, where players wear helmets and approach contests with their heads, and the Australian codes, where the head is considered sacrosanct in terms of tackling.

American footballers, who are generally heavier depending on the positions they play, were exposed to cumulative knocks in training as well as games from their progression through school football to collegiate and professional ranks.

Players in the AFLW and JLT Community Series, the AFL men’s pre-season competition, wore movement sensors behind their ears this year to track effects of body contact. A Stanford University study showed that an offensive lineman in US collegiate football wearing a similar device suffered 62 hits in one game. The impact on the player’s head with each hit was comparable with what would occur if he drove his car into a brick wall at 48km/h.

In 2015, Randwick’s director of rugby, Nick Ryan, said they were surprised at the impact of repeated hits — often at lesser force — after a similar trial.

“What we’re finding is … the accumulative hits, the small and medium range hits that happen multiple times during a game, are the things that are the most destructive,” he said.

The AFL has become mindful of the impacts of concussion, with guidelines related to testing, returning to the field and recovery becoming more stringent. Growing international awareness, combined with several instances in recent seasons of players retiring prematurely due to concerns about the impacts of repeated concussion, have driven change.

It is becoming rarer for a footballer who has been concussed in a match to step out in the following week’s game.

St Kilda defender Sean Dempster is the most recent footballer to retire due to fears concerning the health impact of repeated concussion or head knocks. Lion Justin Clarke retired aged 22 last year after a shocking knock during a pre-season match. Leigh Adams, Brent Reilly, Sam Blease and Matt Maguire are others who have ended their careers due to concussion in recent years.

“(The AFL) is keeping up with the latest research and I think the management of the player, when he gets injured, is exemplary,” Larkins said.

He said it was worth noting the AFL Tribunal had become tougher this year on incidents that saw players being struck in the head. But he was critical of the five-week NRL ban handed to Canberra’s Sia Soliola for a high tackle on Melbourne’s Billy Slater last weekend.

Storm doctor Jason Chan told the NRL judiciary that Slater, who was unconscious for several minutes, had no recollection of the previous two weeks.

“If something similar were to happen in the Hawthorn and Sydney game (tomorrow night), the player would get months,” Larkins said.

The US study showed brains from deceased high school players showed mild impairment, while those from collegiate and professional levels were more severe. But even those with mild cases suffered symptoms in regards to their cognition, mood and behaviour.

“There are many questions that remain unanswered,” McKee said. “How common is this in the general population and all football players? How many years of football is too many? And what is the genetic risk? Some players do not have evidence of this disease despite long playing years.”

The NFL agreed the study was important for advancing science related to head trauma and said it “will continue to work with a wide range of experts to improve the health of current and former NFL athletes”.

After years of denials, it acknowledged a link between head blows and brain disease and agreed in a $1 billion settlement to compensate former players who had accused the league of hiding the risks.