The Judy Murray method - how to raise a sporting star

SO, you want to be the next Judy Murray? It is a worthy ambition. Although sporting parents often get a rotten press, the reality is very different.

Most parents of sporting stars are as inspirational, in their way, as the children they nurtured. Judy Murray, a former professional tennis player from a small town in Scotland, spent almost every evening coaching her two boys, Jamie and Andy, on public courts.

When Andy reached 15, she and Will, Andy's father, gave up their life savings to send him to Spain to turbo-charge his development. "It was a privilege to pay the money," she has said. "We wanted him to have every opportunity to fulfil his potential."

Richard Williams, the legendary father of Venus and Serena, was equally devoted. He took a shopping trolley full of tennis balls to courts in Los Angeles every night so that he could hit with his daughters. They were out there so long that, by the end of practice, Serena felt that her arms were "about to fall off".

The girls did not have access to the country clubs that symbolised the middle-class privilege of American tennis (the courts where they played were riddled with bullets from battles between gangs). But they had a ferocious work ethic, and a father who devoted every day to their development.

But let us take self-sacrifice as a given. Most parents are willing to support their children, sometimes going to extreme lengths. What are the other, more elusive dimensions of successful parenting? What are the processes that unlock success? And how to avoid the pitfalls? Here is a five-step guide:

1. Turn off The X Factor

Perhaps the most destructive myth is the idea that certain kids have their greatness preordained. It is the idea that David Beckham had football encoded in his DNA and that Tiger Woods was born to be a great golfer.

This is damaging because success is not predetermined in any straightforward sense. Roger Federer may look as if he is a natural but that is because we have not seen the astonishing amount of practice that went into his mastery. Complex skills like hitting a moving ball, or playing chess, are not encoded in the genes. They are learnt over thousands of hours of high quality practice.

This is important because youngsters who are preoccupied with talent tend to be less motivated and far less resilient. Kids who think they are super-talented, for example, tend to become lazy (why bother to work hard when I can float to the top, buoyed up on my superior genes?). And kids who fear they lack talent, perhaps because they are lagging behind a peer group, tend to give up (I am not cut out for tennis, or maths, so I may as well try something else).

To put it simply, the very idea of talent can be a psychological obstacle to success, as Professor Carol Dweck of Stanford University has demonstrated. She argues that parents should praise children for effort rather than talent. When a youngster does something well, don't say "wow, you are really gifted". Instead, say: "wow, you worked really hard". This gets youngsters to recognise that, if they want to get even better, they will have to work even harder.

Popular culture is corrupting in this respect. Shows such as The X Factor connive at the seductive idea that success can happen overnight. But this is not the way it happens in the real world, and certainly not in tennis. The danger is that a youngster will pick up a racket, discover that they cannot hit the ball like Andy Murray, and conclude that they lack "talent".

So, they try something else. They don't stick at it. They drift from activity to activity, often demonstrating initial zeal, but never any staying power. The problem is not a lack of drive or hunger, as parents often suppose. The listlessness is the manifestation of a deep (often subliminal) belief in the importance of talent.

Parents should therefore switch off The X Factor, or at least giggle at its desperately superficial construal of success. Equipping youngsters with an understanding of the transformational power of hard work is the single most effective way to unlock their potential at school and on the tennis court.

It is the thing, above all else, that characterised the likes of Ted Beckham and Earl Woods, father of Tiger.

2. Kiss them when they lose

This is the area where you hear the majority of sporting horror stories. Parents who are so obsessed with the success of their offspring, they lose sight of the fact that they are children.

In my table tennis career, I saw it all. Parents who shouted at their children if they lost, who made them cry, who turned defeat into a crime. One dad lavished his son with love when he won, but cold-shouldered him when he lost. It was a form of abuse - and it left permanent scars.

There are, of course, examples of overbearing parents who have taken their kids to the top, albeit at huge emotional cost. Mike Agassi is one example, if the description by Andre in his autobiography is anything to go by. But in my experience, most successful parents are those who want their kids to win, but who let them know that they will love them if they lose.

As Judy Murray put it: "My boys knew I would love them come what may. That was never in doubt."

3. Get them out of the UK

Many sporting parents put in the hard graft, hitting with their kids night after night. But at some point, a parent must recognise that they have taken their child as far as they can. They have to find a coach to take them to the next level.

It is not easy to let go. But as the sporting world has become more professional, the importance of coaching has become ever more evident. If you look at successful nations it is almost always because of superlative coaching (Spain at football; Britain at cycling). Innovative coaches figure out ways to build mental strength (think Andy Murray and Ivan Lendl) and accelerate skill acquisition.

When it comes to tennis, British coaches have long been behind the curve. That is why Judy was so keen for Andy to go to Spain. She and Andy might have chosen the Bollettieri Academy in Florida, but settled on Sanchez-Casal in Barcelona.If Murray had remained in the country, Sunday would never had happened.

4. Have a fat wallet

Following on from the previous point, it is generally parents with the most cash who can afford to hire the best coaches and access the best facilities.

At one level this is obvious: a child whose parents can't afford to buy a tennis racket is not going to make it. At another level, it is political: it explains why children who attend independent schools win a disproportionate number of Olympic medals.

One of the characteristics of progressive sporting systems is that they attempt to give all children the chance to develop their abilities. But such things can never be fully equalised, regardless of political will. That is why money is as implicated in sporting success as it is in other kinds of success.

Parents with large bank accounts have a huge advantage (with notable exceptions: see the Williams sisters).

5. Give them lots of competition

It is easy to caricature left-leaning local education authorities, but there was a time when the idea of competition was under threat. Winning was considered elitist and losing was regarded as damaging. This led directly to sports days where everyone won a prize.

This was silly in all sorts of ways. For a start, it undermined any work ethic. By lowering standards, it led to students who felt entitled to lavish praise, regardless of where they finished, or how hard they had worked. But it was also silly because it failed to recognise that competiveness is central to human psychology.

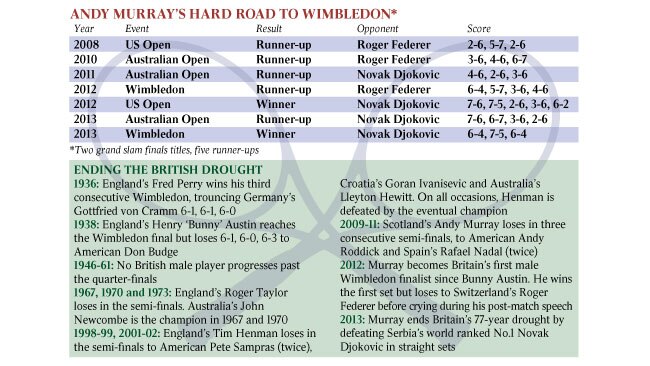

That is why parents should always give their children opportunities to compete. Winning and losing, and figuring out how to cope with both, is empowering and educational. Indeed, it was a seminal part of Murray's development. As he said yesterday (Monday), it was defeat to Federer in Wimbledon last year that turned him into a champion.

SO, you want to be the next Judy Murray? It is a worthy ambition. Although sporting parents often get a rotten press, with stories of demented Tiger mums living their lives through oppressed kids, the reality is very different.