Sport is bigger than the blokey footballing monoculture

SPORT has a bad reputation. We may as well hang a sign over every stadium, "Bigots R Us!"

SPORT has a bad reputation. We may as well hang a sign over every stadium, a banner over every sports page in every newspaper, put a little logo on every sports channel: "Bigots R Us!" Sport is widely seen as a hotbed of unreconstructed male chauvinism and vindictive homophobia.

Next year we have a World Cup, a month-long festival that celebrates a single sport and a single sex. It's an event and a sport that is traditionally homocentric and homophobic: all us blokes together, but not like that, no way, heaven forfend. The mass spiritual intimacy of such a gathering is dependent on the mass rejection of physical intimacy.

So naturally sport is the target of anyone with anything that could remotely be termed a liberal agenda. Sport is the ultimate eye-rolling, shoulder-shrugging, deep-sighing example of the crass rejection of any of the advances society has made elsewhere.

I expect, dear reader, you have occasionally stared glassy-eyed at a television quiz show - one of those programs designed to throw the ignorance, greed and lust for fame of the general public into sharp perspective and seen a blokey contestant light up on learning that the next subject is sport. "What are the four disciplines in women's gymnastics?" Watch the wince of betrayal. "What are the three disciplines in eventing?" Or: "What is the only jump in ice skating which you enter facing forward?"

Not fair! He was expecting a question like: "What are the two Barclays Premier League football clubs that operate out of Manchester?" Or perhaps, "Who won the World Cup in 1966?" Instead, he gets questions about sports that involve women. And sometimes, God help us, gay people. Every fibre of his being wants to scream: "This isn't sport!"

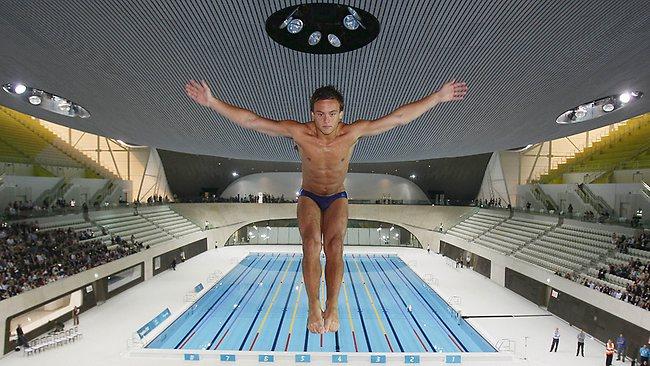

Yet it is. Which brings us to Tom Daley, of course. Daley's brave. If you have any doubt at all about that, climb a 10m board and look down. I did that at Crystal Palace years ago. The place looked different, the water looked different, the whole bloody world looked different. In diving you need a certain amount of physical courage even to take part: all sport should be like that.

I was there - not on the top board, though - at the platform diving final at the Olympic Games last year. Daley was back in the pack in a very tight competition. The big dive, the highest-tariff dive that year, was the 4 1/2 forward somersaults, tuck.

You come out of the last rotation at the speed of an express train. Daley had been having trouble with this dive, but in the Olympic final he nailed it. You could hear that clean, almost splashless thrum of the perfect entry. A sound that meant medal.

That's classic Olympic courage: finding just the right response at just the right moment at an occasion that only comes once in four years. And now, of course, Daley has had the courage to come out: to explain to the world that he's in a relationship with a man. And as he's not a footballer, the overwhelming response to this has been supportive and admiring. Just what you'd expect from a society that celebrates Alan Bennett, David Hockney and Stephen Fry as living national treasures.

This week we read about two Great Britain and England hockey players who entered a civil partnership last year. Married each other, in effect. They are now Helen and Kate Richardson-Walsh. Again, this announcement caused no great outrage; it's the way the world is.

It needed bravery to take such a step, just as it requires physical bravery to take part in top-class hockey. Kate had her jaw broken in the opening match at the Olympic Games last year, came back two matches later and helped Britain to its first Olympic medal in 20 years: just one more inspiring tale from sport's bottomless locker.

Sport is bigger than we think. That's not especially obvious at this time of year, when the trinity of big-time ball sports, male versions, dominate the agenda and the kick-ball game bullies the other two in hot pursuit of its ambition to turn all sport in a footballing monoculture.

Yet as a conservationist I know that truth, meaning, resilience, strength and the long-term future depend on biodiversity - so it's as well that sport continues to provide it. As I survey the entries for the annual Magic Numbers competition I discover glorious and unexpected numbers from sailing and the horsey world, numbers celebrating women such as Christine Ohuruogu, who has never really received her due.

There are two matters arising from this. The first is that people who condemn all sport as inherently illiberal and all sports enthusiasts as bigots are taking as narrow a view of sport as the sporting bigots themselves. Sport is large, it contains multitudes. It doesn't reflect a tiny fragment of society, it reflects an awful lot of the way we live now, which is why Daley's declaration was greeted with such widespread good cheer.

The second is that sport does a remarkably good job of concealing its greater nature. There are many newspapers in which, on any given day, you could find no evidence that women have ever played sport in the entire course of civilisation. This is not a straightforward issue: in the media, we don't have complete freedom to set our own agenda. We must also service the requirements and expectations of our audience.

For some people, sport represents relief from the real world, an escape into the comfortable and anachronistic banalities of football banter and golf-club pontificating. Sport can be a play-world in which the old certainties can be savoured once again - but even in the most ancient institutions things still change.

Wisden Cricketers' Almanack made Claire Taylor one of the five cricketers of the year for 2009 and this year ran a piece from Steven Davies, of Surrey, who has come out as gay.

Football lags behind the rest of the sporting world here. So does golf, an Olympic sport that continues to hold leading tournaments at clubs that won't accept women as members.

It's not that sport lacks bigots and bigotry, it's just that this is not the whole story.

Sport is many things and many views. Sport reflects the society around it -- and on occasions has the honour of playing an active role in change. Sport has done this in the matter of race and religion: via John Barnes, Mo Farah and many others. It has brought us countless examples of strong and courageous women: Ellen MacArthur, Beth Tweddle, Jessica Ennis-Hill, Charlotte Dujardin and so forth. It also brings us the brilliant and the gay: Martina Navratilova, John Curry, Carl Hester, Tom Daley.

Sport - a point made by my colleague Matthew Syed this week -- is about the elementally simple preoccupation of who beats whom. Ultimately sport doesn't care about anything else. In its pared-down simplicity, sport can't help but be about truth. And truth is the stuff that frees us. Sport - despite itself, despite the bigots, despite so many of its traditions, despite the atavistic footballing mentality - is at its base all about freedom and truth and bravery.

THE TIMES