For the same reason that Sachin Tendulkar loves coming to London to escape the goldfish bowl that is Mumbai, Kohli and his bride were looking forward to enjoying the freedom that this corner of the world would allow, shorn of paparazzi and cricket lovers as it usually is.

Then they strolled into a coffee shop in the city, bumped into three tourists from India and had to beg them not to break the news of their whereabouts on social media.

Kohli is not the first captain of India to marry into Bollywood royalty – the Nawab of Pataudi beat him to it in 1969 – but the scale and reach of his combined celebrity with Sharma is without precedent.

Any appearance, photograph or utterance is newsworthy to their followers on social media (126 million between them on Instagram), and for India’s celebrity-hungry networks. Imagine the attention lavished on the royals here and then some.

That his decision to forgo the bulk of the Test series in Australia, which starts next month, so that he could attend the birth of his first child elicited such little fury says much about how the game has changed for the better.

I may have missed it, but I haven’t seen much adverse comment about a decision that, not so long ago, would have brought plenty.

There was a brief statement from the Board of Control for Cricket in India, the country’s governing body, acknowledging paternity leave had been granted, and that was that.

It was only two decades ago that Jonty Rhodes, the South Africa batsman, became the first cricketer formally to be given paternity leave by his employer, and less time than that when the decision of an England captain, Michael Vaughan, to miss an hour of play during a Test to attend his daughter’s birth provoked something of an outcry.

I can even remember some grumbling when Nasser Hussain took his wife to Australia before the team so they could be in situ for the birth of their second child.

Before that, although players missed tours from time to time for family reasons (usually tours to India – how times have changed), it was expected that cricket came first and family second. There is a famous photograph of Allan Border taking guard in a Test against India at the Sydney Cricket Ground in January 1986, with the giant electronic scoreboard in the background announcing the birth of his daughter Nicole.

“Congratulations on the birth of your daughter Nicole, born this afternoon” was the notice, but Border’s back was turned as he took guard.

Border had wanted to get to Brisbane for the birth, and moved down the order in the second innings as Australia batted for the draw, hoping that he would be able to slip away.

Wickets kept tumbling and so he was forced to bat for country rather than family and missed the birth, as he had his first child Dene, because he was on tour in the Caribbean two years earlier. On that occasion, the telephone exchange broke down as he was waiting for news and he was left none the wiser for some time.

Border did make it to the births of his third and fourth children, which is more that can be said for generations of cricketers that came before him.

Flicking through Gideon Haigh’s magisterial The Summer Game, an overview of Australian cricket in the 1950s and 60s, finds so many examples of cricketers away for months on end, missing births and those precious early months.

Usually news was imparted by telegram or phone call, often delayed for days. Children were sometimes named for the port of call in which the player found himself or, in Keith Miller’s case, for cherished opponents.

Miller named his third boy, born shortly after the 1950-51 Ashes, Denis Charles, in honour of Denis Compton. Lengthy absences, of course, played havoc with marriages, Bill Edrich taking the game’s pennant in this regard, going through the marriage ceremony five times in all.

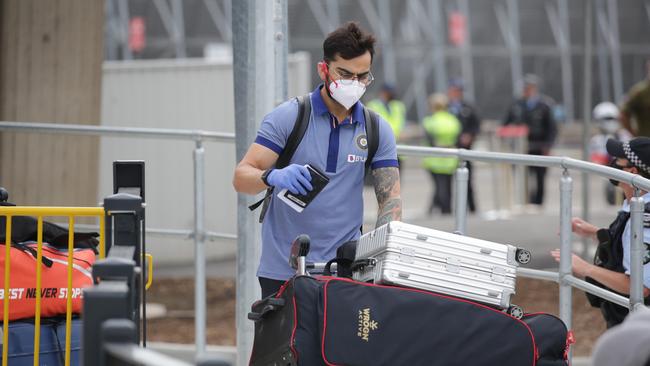

Kohli’s absence in the last three Tests will hurt the four-match series, for sure. The broadcasters and Cricket Australia, who face severe post-COVID financial challenges, will be quietly regretting the timing of his departure and the captain’s absence will diminish his team significantly, so dominant is he as a player and leader. His absence skews favouritism to Australia.

Times and expectations change and sport usually moves in step with that. In this instance, though, as well as moving in step with what is expected of modern fathers, there is also an important shift away from present trends.

In India especially, but in professional sport more generally, the tone of coverage, often ridiculously, suggests that nothing is more important than sport and those who play it. Kohli’s decision is a welcome reminder otherwise.

The Times

When the India captain Virat Kohli married the Bollywood actress Anushka Sharma, their choice of honeymoon destination was telling. They went to Rovaniemi, the capital of Lapland in northern Finland. As the official home of Santa Claus, and a place to watch the northern lights in full splendour, no doubt the city has its charms, but the appeal was its remoteness from cricket, about five miles from the Arctic Circle as it is.