It revealed no such thing, of course, although it did generate a lot of heat and noise. Other media outlets were duty-bound to report the story, which, in turn, forced the players, coaches and administrators to deny it, thus creating a new wave of noise.

Watch The England v NZ Test Series Live & On-Demand on Kayo. New to Kayo? Try 14-Days Free Now >

Everyone had their say; the uninformed became, perhaps, a little more cynical about the veracity of the international cricket they had watched, and the game stumbled on, slightly tarnished in the eyes of some.

The investigation produced two programs, Cricket’s Match Fixers, aired months apart. In May 2018, one strand of the program alleged that three (unnamed) England players had been involved in spot-fixing during the Test against India in Chennai in 2016, scoring at a predetermined rate during passages of play. Similar allegations were aired about the Ranchi Test the following year between India and Australia, when two (unnamed) Australian players were similarly accused.

In the second program, aired in October 2018, we travelled back in time to 2011-12, when 15 matches were put under the spotlight. The allegations claimed spot-fixes in games involving England, Australia and Pakistan. No names were mentioned.

At the centre of this fixing free-for-all was the international man of mystery Aneel Munawar, who, like many such characters, was not shy of bragging about his influence and ability to influence passages of play. He even got the subtitle of the program: “The Munawar Files.” With the undercover journalist offering Munawar money for information as part of the sting, quite who was duping who here was unclear.

In these pages, I did not give any credence to the main claims, although I did say the allegations around the fringes of the game — a stadium manager, a micro-tournament in UAE — which is where most danger lurks at present, were more plausible. But, whether by design or not, the plausible bits were hitched to more newsworthy claims of fixing at the highest level, the detail of which was desperately thin.

I wrote that I would be “astonished if there was any credence to the claims”, that “it makes no sense” and that I was “highly sceptical”. In all likelihood, I wrote, there will be “some elements of the documentary that produce some substance but it will not involve those unnamed players in Test matches”. Before surrendering to weary cynicism I wanted to see a lot more detail and evidence.

Al Jazeera did not take kindly to the doubters. “The ICC, together with certain national cricket boards and their supporters in the media, has reacted to our documentary with dismissals and attacks on the messenger. We are particularly struck by what appears to be a refusal from certain quarters to even accept the possibility that players from Anglo-Saxon countries could have engaged in the activities exposed by our program.”

Having played through the 1990s and having written a book on betting and gambling, I like to think I come to this topic with my eyes open: the doubts had nothing to do with the nationality of the players and teams allegedly involved, and everything to do with the program itself.

The ICC Anti-Corruption Unit could not be so blithely dismissive, of course. This week, after an investigation taking more than two years, involving hundreds of man hours and involving four independent experts on cricket, statistics and betting, they reached their conclusion: the allegations were “implausible”.

Alex Marshall, the head of the ACU, said: “There are fundamental weaknesses in each of the areas we have investigated that make the claims unlikely and lacking in credibility.”

At the time, the ACU had sought access, not given, to the unedited and uncut conversations between Munawar and the journalists and they have still not been given access to that. Al Jazeera has said it has handed the evidence to law-enforcement authorities, but none of these agencies has seen fit to take further action.

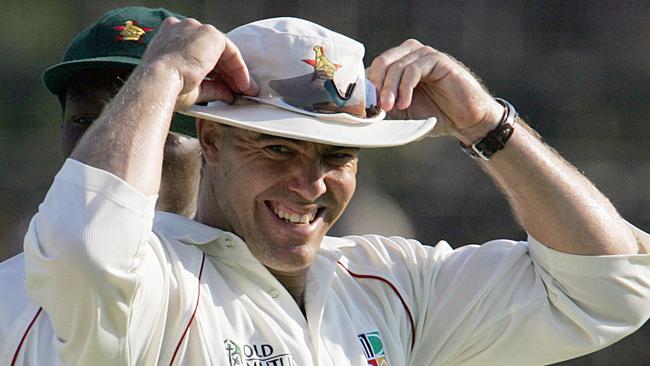

The ACU has been busy of late, and cricket is wise not to sleep easily. There are between 40 and 50 live investigations on top of the 20 cases successfully concluded over the past three years, with participants found guilty or having reached an agreed sanction. Some big names, post-playing career, have fallen: Sanath Jayasuriya and Heath Streak among them.

Corruption and fixers are a fact of life; the game is always vulnerable. Right now, though, the danger is in areas markedly different to those in the 1990s.

One of the reasons why parts of the Al Jazeera documentary looked at a stadium manager and a pop-up tournament in UAE is precisely because it is harder to get at well-paid, well-scrutinised players in top-rank international cricket. It is in the less well-lit corners of the game that the light from the investigative torch will be most revealing.

I remember well the heightened sense of activity when the first program aired during a match at Lord’s in 2018: everyone scrabbling around to try to make sense of the allegations; many column inches filed; much hot air expressed; a lot of doubt and cynicism about the game swirling around. The usual suspects were wheeled out to sound off on how corrupt the game was at the highest level and how naive those who did not give much credence to the claims were.

This week, not so much. The ICC’s findings were largely lost under the avalanche of news coming out of Australia, given all the flapping going on after Cameron Bancroft’s suggestion that the knowledge of ball-tampering was more widespread than a review concluded.

The denials of the Australia bowlers from the fateful Test in Cape Town in 2018, England’s squad for the opening Test of the summer and the Ashes schedule took up more space and interest.

Accordingly, there has been far less exposure for the ICC’s sober findings than the original program. Al Jazeera’s investigative unit tweeted a brief response, calling the report a “whitewash”, criticising the ICC for being a conflicted organisation responsible for clearing up its own mess and standing by its original investigation. My view has not changed, either.

The Times

When Al Jazeera’s investigative unit aired a documentary on match-fixing in cricket three years ago, the broadcaster did not undersell its claims. According to the program, portions of Test matches involving India, England and Australia were allegedly fixed. “Our 18-month investigation reveals that match-fixing in cricket is more widespread than ever,” one of the journalists behind the investigation claimed.