Football: Why the first title in 30 years means more to Liverpool fans

Covid may have limited how fans marked Liverpool’s first title in 30 years, but it was a small price to pay for a return to glory.

On Merseyside, they have had 30 years to think how they will celebrate winning a 19th championship. Peter Hooton had never imagined that it might be in his back garden, having to restrain himself from hugging his nonagenarian father.

For reasons that would have made no sense in 1990 (or even six months ago) when Alan Hansen, now 65, was the last Liverpool captain to lift the league trophy, Hooton has to think of the health of his dad Eric, who watched his first game at Anfield before World War II and remains a season-ticket holder at 91.

Given all the longing for this moment, the craving for this trophy, the hope invested and the years when it seemed as though it might never happen, restraint will have not come easily.

“I’ll have to stop myself,” Hooton says. “My dad went to the 1965 FA Cup final and came home to tell my grandad we had won the cup and he burst into tears. That’s what it meant. That’s what this means now. Everything about it is bizarre but not the emotion.”

In Liverpool, they will have celebrated in living rooms. They will have come out on to the streets to salute joyful neighbours. They will have felt a great surge of pride, but in circumstances that no one could have foreseen, there will have inevitably been something muted in a public outpouring that would have normally been deliriously communal.

This piece set out back in January, when Liverpool were already champions-elect and COVID-19 was still only a problem on the other side of the world, to ask whether the title would “mean more”, as Liverpool’s marketing department love to proclaim. Mean more for the seemingly endless wait; for having to endure Manchester United overtaking a haul of 18 top-flight titles with 20 of their own. Mean more simply for being Liverpool, which can lay claim, as much as anywhere, to being a footballing city.

Given that Anfield lies empty, and hundreds of thousands cannot gather in the city centre (not safely, anyway) for a trophy parade, does coronavirus force us to ask whether it means less?

“Not to see them lift it in person is tough,” says Steve Rotheram, Liverpool’s first Metro Mayor. “It’s a blow to the solar plexus as a fan, a season-ticket holder. The whole thing will be more reflective. We won’t be out on the streets in the same way.

“I’ve had friends from other clubs winding me up, calling it The Corona Cup. I just hope in time people recognise the unbelievable season we’ve had. It shouldn’t ever be underestimated just how good Liverpool were.”

Smashing Crystal Palace 4-0 on Wednesday, showing all the class of champions more than 20 points clear of a brilliant Manchester City, more than 30 ahead of third, felt like the sort of emphatic declaration of excellence these strange times needed.

No need for asterisks — this success is deserved, and momentous. Liverpool have enjoyed their great European triumphs, but there is something about domestic dominance that brings a deeper, richer sense of pride.

Perhaps you can see it in the Museum of Liverpool, where you walk up the stairs and see a big sign proclaiming “The People’s Republic”. Or in the shop where they sell Scouse passports. And in the booing of the national anthem whenever Liverpool play at Wembley, declaring a sense of separatism.

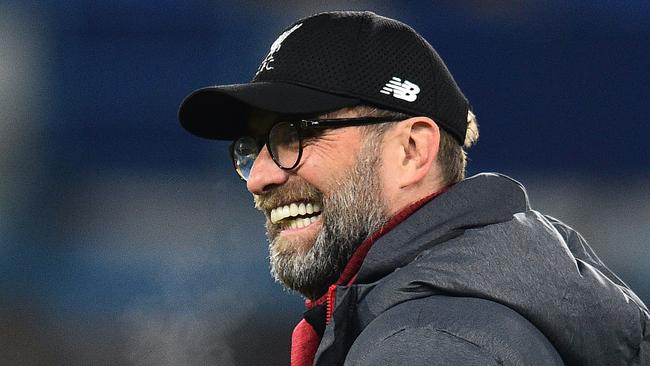

To be kings of England after so long is a landmark triumph and, if it cannot be marked as they would like, reassurance comes in the unwavering belief that this success is not a one-off. They are so confident of a glorious new era under manager Jurgen Klopp that, in a world before coronavirus, Hooton, singer with The Farm and a leading member of the Spirit of Shankly fans’ group, gathered his mates in a Liverpool pub in January and asked them to toast the near miss of not winning the title in 2013-14.

To have won then would have been a false dawn, he says. Now there is no argument that Liverpool are the best team in the land. That is why it means more to him — not that he is rushing to use the phrase. “That is a club slogan, not really the fans,” Hooton says. “It’s a marketing tool. Thirty years is what means more. To wait so long, so many close shaves. In 2008-09 I thought we had a title-winning team, when we beat United 4-1 at Old Trafford. But (Alex) Ferguson had that ability to get his team over the line. (Liverpool came second by four points.)

“As for 2013-14, I got everyone in the pub to toast not winning it then because it would have been the false dawn of Brendan Rodgers. It might sound strange but we would never have got Klopp and he, for me, is reminiscent of (Bill) Shankly growing up. A messiah.”

It is a perspective echoed by Roy Evans, who has seen it all at Anfield as a player, coach, manager and now club ambassador. He thinks back to where Liverpool were when he was a youth player in 1964 and he joined the Shankly revolution.

The great leader would change next to him, hanging out with the young players rather than the first team before they all travelled to Melwood on the bus.

“Shanks would come in and say, ‘Great day today, son’, even as the wind howled and it poured with rain,” Evans says. “He was Chairman Mao. He said it and it became fact.

“There was no divine right then that Liverpool would be this huge, successful club and become one of the biggest in the world. Everton were more successful. We were a Second Division club until Shanks came along with his conviction, his positivity. We have been seeing something similar under Klopp. I feel it as a fan. The whole place is energised. He gets the club, the people, the city.”

As Metro Mayor as well as a lifelong Red, Rotheram sees the wider impact of what Klopp has been achieving. A buoyant Liverpool team bring so much more than sporting pride to a city that has faced so many socio-economic difficulties.

“There is a piece of work that was done by (Liverpool chief executive) Peter Moore to identify the monetary value of Liverpool FC to the city region,” Rotheram says. “And it’s nearly half a billion pounds of GVA (gross value added) per year.”

The appeal of the club around the world with their history and heritage was one of the main reasons John W. Henry noted that “this could be a steal” when Fenway Sports Group was considering buying the club in 2010.

At the risk of provoking loyal fans of any other club — after all, who can say it means more than to the supporter who has been following Stockport County home and away for 20 years? — the owners have been pushing that slogan that Liverpool offer something unique in football. A video narrated by Klopp over images of the Kop singing She Loves You, and the Shankly Gates, and great Liverpool sides through the ages, tells us that “for others it is a sport, for us it is a way of life … they sing, we have an anthem … they have supporters, we are a family”.

As civic leader, Rotheram embraces the message, knowing there are some tired perceptions to overcome. “We are the fourth most visited destination in the whole of the UK,” he says. “And the more people come, whether it is for the football, the Beatles or whatever, the more they go away and tell what they’ve seen and it’s not post-industrial decline or some of those old stereotypes.”

He tells of facing enduringly lazy stereotypes as an MP in Westminster. “I sat down at a table with other MPs and someone went, ‘You know he’s from Liverpool. Mind your bags.’ And I reacted to it. Then I got told, ‘I thought Scousers had a sense of humour’.”

One effect, he says, is to bind the city together. And then there is Hillsborough. Rotheram stopped going to football for 18 months after the 1989 disaster that claimed 96 lives. “Hillsborough will be very strong in our thoughts at a time like this,” he says. “It is still very raw to a lot of people. Their support has been forged with this sense that people weren’t listening, that we had to stick together and no matter what was thrown at us we had to bounce back.

“United fans had it with 1958 (the Munich air crash) but that was a few decades earlier. Ours have grown up with it. It’s part of our identity.”

So it does mean more? “If you spoke to fans of other clubs, they would feel they have this connectivity, but I’m not sure it is ingrained in the emotional psyche of the fans the same way,” Rotheram argues.

In normal times, he would have headed for the town hall to join a mass celebration. Instead, like Hooton, Rotheram was planning to celebrate the title at home with close family. His grown-up son was born after Liverpool’s last championship. “And I’m thinking back to when I would expect us to win it every year,” he says.

For so many, this is a first. The climax of a seemingly endless wait; not just of 30 years but recent months when Klopp ended up googling “asterisk” in case the campaign was never concluded.

“I am just made up for the younger generation who have never got to experience anything like this,” Hooton says. “At least we’ve been able to look forward to it. Don’t worry, we’ll cherish it.”

THE TIMES

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout