Celebrating Dickie Bird at 90: Cricket’s first, and last, celebrity umpire

The most famous umpire the game has known turned 90. MIKE ATHERTON pays tribute to the one and only Harold “Dickie” Bird.

So long ago now that the details are hazy, but given I was captain, I guess the idea must have been mine. Anyway, no matter whose idea it was, we, along with the India team, lined the entrance from gate to ground and gave Harold “Dickie” Bird a tremendous welcome. He blubbed a little, dabbed a tear or two from his eyes, waved his hankie to the crowd and then, five balls later, gave me out leg-before for a duck. If Dickie gave it, it must have been plumb.

The most famous umpire the game has known turned 90 yesterday (Wednesday). It was in June 1996 that he officiated in his last Test, at Lord’s, and the ovation from both teams felt a natural thing to do at the time. But whereas it is now common to applaud a great player to the crease for the final time, it wasn’t then: Dickie got a grander reception in his final Test than many of the greatest players the game has known. It is worth pondering why.

He was the first, and undoubtedly the last, umpire whose celebrity stretched beyond the confines of the sport. The game is about the players, of course, and not officials – who cares, frankly, what a referee or an umpire has to say? – but few begrudged Dickie his fame. As Geoffrey Boycott said about his old friend: “There was no malice in any story about Dickie Bird.”

He was famous, to a degree that is hard to comprehend now for a cricket umpire. His remains one of the best-selling sports autobiographies of all. He appeared on the talk shows of the time, made his selections on Desert Island Discs, and was ambushed by Eamonn Andrews for This is Your Life. During the 1996 World Cup, he starred in an advertising campaign for Pepsi – “there’s nothing official about it” – alongside the superstar players of the day.

A statue was erected of him in Barnsley, and he was made Yorkshire Personality of the Year in 1977 – a short long-list, one would have thought. His biography contends that he was asked to judge the annual talking bird contests at the NEC, Birmingham, whereupon he was bitten one year by Billy, an Amazon parrot from Aylesbury, and Doodle, an Australian cockatoo, the next. He was, wrote Matthew Engel in Wisden, the first “to combine the distinct roles of top-flight umpire and music-hall comedian”.

This fame had little to do with his decision-making, highly competent though that was. He was renowned as a “not-outer” in the days before Hawk-Eye and the Decision Review System (DRS) suggested more balls would hit the stumps than otherwise imagined. Umpires are more trigger-happy now as a result. Dickie erred to caution, but he was consistent in his restraint and the players knew where they stood.

They liked his manner. Some umpires get carried away with their authority and in those moments of inevitable tension sometimes force players to attention rather than defusing situations with a touch of humour or a twinkle in the eye. A game I played in once found Dickie, having dropped his counting marbles, crawling around on his hands and knees, shouting: “‘Ave lost me marbles! ‘Ave lost me marbles!” He could always poke fun at himself.

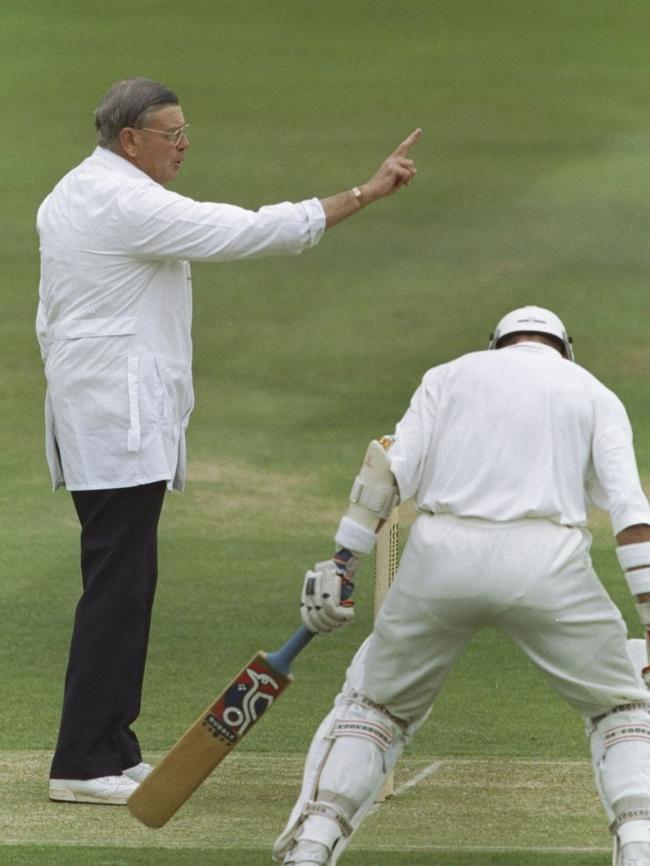

When he gave a decision, he did so without affectation, instead applying the utmost seriousness. Some umpires are prone to give signals in a way that plays to the dramatic but when Dickie gave a batsman out, he raised his finger and waggled it in the air briefly, almost admonishingly, sometimes saying “that’s out!” and then quickly put it back in his coat pocket, as if he had been embarrassed to do so.

Rather, supporters warmed to him because the minor calamities that can attend a day’s play always seemed to follow him around. At Headingley in 1988, on a fine summer’s day, water suddenly started bubbling up from the drains below the outfield, much to Dickie’s consternation. When sunlight reflected from the greenhouses next to Old Trafford in 1995, causing a glare the intensity of which prevented play, Dickie was in the middle. “Rain and bad light have followed me around all my life,” he once said.

He was a modest player in his day, a little for Yorkshire and then for Leicestershire, and that he failed to make the top grade as a player – two hundreds in 93 first-class appearances – must have given him an appreciation for the craft of umpiring that followed. His love of the game – the bachelor in him always said he was married to it – shone through from first to last. The natural English way is to be a little reticent about such matters as love of county, country or monarchy, but not Dickie.

He was of a generation who must have appreciated their good luck to have both arrived after the first great war, and be too young for the second – and to be in adulthood as the 1950s and relative prosperity arrived. Cricket was religion in Yorkshire then, and was a central part of the national conversation during his working life.

DRS has reduced umpires to little more than hat-stands, with decisions increasingly made or confirmed by the TV umpire a distance away. The chance for an umpire to take centre stage, as Dickie did unknowingly from time to time, has faded.

His popularity hasn’t dimmed. When, during the pandemic, BBC Look North went to Dickie’s house to record a short piece, it garnered more than a million views on social media. It was not hard to see why: there was Dickie, 88 years old, doing his shuttles in the garden and encouraging others, who might be lonely and stuck inside, to get out and about for the good of their mental health. He wasn’t afraid to show his vulnerability. “It’s been very hard,” he said.

David Hopps, his biographer, put his finger on Dickie’s enduring popularity. “There is no side to Dickie,” he wrote. “In a lifetime committed to the game he loved, Dickie Bird communicated a sense of joy. For all the angst and heartache, he lived life to the sound of laughter.”

The original not-outer, remains not out, still.