Now, after another staggering day at this most storied of cricket grounds, there is a new set of highlights for future generations and a new Headingley hero to feast on, after Ben Stokes played one of the greatest innings in Test history to keep the Ashes alive.

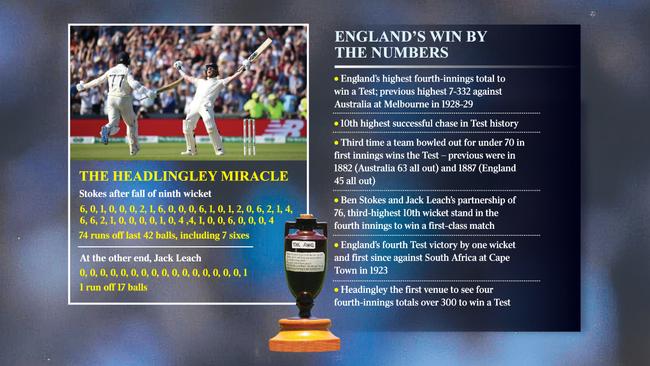

Where to start with a day that defied convention and belief, and will live long in the memory for those lucky enough to have witnessed it? Stokes’s innings was an unbeaten hundred of the highest order, combining craft, skill, versatility and, during a last-wicket partnership of 76 with Jack Leach, great daring, power and inventiveness. Sages and wise old heads were wondering when they had seen batting to better it, with a match and the Ashes on the line, and it was hard to come up with an answer.

Most of all, coursing through that innings, through the initial bloody-minded defence that brought him his slowest Test 50 — at one stage he had scored nine runs from 81 balls — through the switch-hits and scoops for six, and the desperate scampered singles and twos, necessary to farm the strike and keep Leach from it, was a never-say-die attitude that has come to define his cricket. While he is at the crease, or with ball in hand, in World Cup finals or Ashes Tests, England are never beaten.

As England supporters revel in the Stokes-inspired magic of the final day, his bowling on the second evening will be pushed to the margins of our memory. It shouldn’t, because without his sustained session-long spell then, there would have been no victory and no innings of consequence on the final day. This match was won not just by a great innings but by a great all-round performance from a man who refused to be beaten.

To recall that second day: Jofra Archer was off the field with cramp and Australia were building a matchwinning lead after England had capitulated. Keen to make amends for his horrendous shot in the first innings, Stokes grabbed the ball from his captain, charged in for 16 consecutive overs, until his only reaction upon taking a wicket was a weary slump to the ground. He took two wickets in that spell, Travis Head and Matthew Wade, and kept his team afloat when they looked like sinking.

It was a spell intended to inspire others but, in the end, he had to do most of the heavy lifting himself.

It was an innings to rank with any that has been played here, surely. In more modern times, three have stood out on this ground for England: Ian Botham’s swashbuckling 149 in that 1981 Ashes Test, that he himself would categorise as a bit of a slog at the start, littered with fluky moments; Graham Gooch’s magisterial 154 against the great West Indies team of 1991 on a treacherous pitch; and Mark Butcher’s 173 in the fourth innings of the 2001 Ashes Test. But only Gooch’s could compare with this.

Butcher’s innings was played in a dead rubber, with the Australians having already cantered to an Ashes win. Here the Ashes were alive, albeit when Leach joined Stokes with the target still distant on the horizon, only just. But they are very much alive now. Having lost a match they believed they had won and, more gallingly, having missed clear opportunities to finish the job, it will be hard for Australia to come back from this.

It was all going so well for them. They had dismissed Joe Root early in the piece before the second new ball was due. Despite not quite hitting the mark with that new ball, they had regrouped, through Josh Hazlewood and Nathan Lyon, taking 5-41 in the hour after lunch. Jonny Bairstow had given impetus to the innings in the morning but once he edged to slip, there was precious little resistance from the lower-middle order, after Jos Buttler was run out calamitously by Stokes who, we can safely assume, will be forgiven.

Throughout all this, Stokes had played watchfully, cautiously even, much as he had during the opening stages of his hundred at Lord’s.

Lyon, who went past the great Dennis Lillee when he snapped up Root with his third ball of the day, having lured the England captain from his moorings, was a threat. Stokes wanted to get past the new ball unscathed, and battened down the hatches for a while. His 50 was a laborious one by his standards, from 152 balls.

The crowd did their best to lift the home side. They had given Root and Stokes a rapturous welcome in the morning, as England set out on their mission of making the 10th-highest run-chase of all time in Tests and the highest in their Test history. They had been hushed for 25 minutes, until the first run was scored, but every milestone brought a roar that could be heard across the Pennines. How they cheered for Bairstow when he drove consecutive fours. How they cheered Stokes when he pulled Pat Cummins for six, a rare sign of aggression. The roar came in waves and waves.

When Stuart Broad was dispatched second ball, leg-before to James Pattinson, reality had hit home. There would be no miracle, no great chase to tell the grandchildren about; no rehash of 1981. The situation was this: England were 73 runs from their target; Stokes was on 61; Leach, fresh from having his leg stump detonated by Hazlewood in the first innings after jumping across his crease as if batting on hot coals, was in and Australia were rampant.

A quarter chance missed at slip by David Warner off Lyon, when Stokes was on 33, had long been forgotten. What did it matter now?

Quite a bit, as it turned out. Although Leach had made 92 against Ireland last month, the chances of him keeping out these bowlers was a different prospect and so Stokes had to farm the strike. The measure of his success was that, in the 62 balls they batted together, Leach was required to face only 17 of them. And, to give him full due, he faced them as well as a No 11 could. Every Botham needs a Graham Dilley, and here Leach was courageous and solid in defence, wiping his glasses down before moving calmly into line against the quicks. Only the running between the wickets, as both men occasionally confused each other, raised the pulse.

Briefly, when Archer had come to the crease, Tim Paine, the Australia captain, had set the field back for Stokes and used two fast bowlers, but when it was clear that he had forfeited some control, Lyon was asked to bring order to proceedings again. Stokes was not for complying: he hit Lyon for four sixes in the next passage of play, not all cleanly hit, but powerful enough to clear the boundary, including one extraordinary switch-hit into the old Western Terrace, a shot so remarkable that the bleary-eyed spectators in there must have wondered as to the effects of their drink.

With that piece of genius, the total required moved below 50. Hazlewood was the next to feel the effects of the Stokes hammer. Four, six, six Stokes went, the first of those boundaries bringing up his hundred, although the victory rather than personal milestones was on his mind, now.

The first of the sixes was an audacious scoop, the second a brutal mow into the Western Terrace. Hazlewood was removed to lick his wounds, although the No 1 fast bowler in the world, Cummins, fared little better as Stokes took him for consecutive fours two overs later, the second of them the hardest shot in the book — a straight drive off the back foot, down the ground. The target was single figures.

Amid the carnage, Australia’s fielding began to falter. With 17 needed to win, Marcus Harris spilled a half-chance from Stokes at third man, and the next ball, Warner could not quite get to a quarter-chance in the deep. Tough, but increasingly they looked like the kind of chances that Australia would live to regret not taking. The game, this most remarkable of games, had a twist yet.

England needed eight to win when Lyon began the 125th over of the innings. Stokes hit the first two balls to deep point and, with everyone on the boundary edge, refused the run. He smashed the third ball over mid-off for six, clearing Marnus Labuschagne, who had just been moved there in place of the beanpole Hazlewood, by inches. The fourth ball yielded no run, after which the field came in. Stokes reverse-swept the fifth ball to Cummins at backward point, stalled, only to look up and see Leach charging at him. The throw from Cummins left a little to be desired; the fumbled pick-up from Lyon even more so, as Leach scrambled back.

That was Australia’s last chance, surely? The next ball, the last from Lyon, was full and straight and hit Stokes on the pad as he aimed a mighty sweep.

Joel Wilson, the umpire from Trinidad, can expect the freedom of Leeds in the days to come as, for some reason, although quite why no one knows, he refused to uphold the appeal. And reviews? Australia had used their last, in desperation, during the previous over from Cummins.

It is unlikely that Stokes had, at any stage, recalled the famous line from Fred Spofforth all those years ago when the Ashes were brought to life (“This thing can be done!”) but four balls later it was done and Stokes, like Spofforth and countless others, went into Ashes immortality. A single from Leach — off the mark from his 17th ball faced — was followed by a thunderous cut to the boundary by Stokes.

He stood, arms raised, roaring in triumph, the ground ablaze, Australia beaten. Leach jumped into his arms and planted a kiss on his cheek and, to their credit, every Australia player came and congratulated him; they recognised greatness in that moment, as hard as it was to contemplate and accept.

Who knows what will happen from here, but World Cup winner that he is, Stokes may garland that memorable triumph with an Ashes moniker. We had Botham’s Ashes in ’81 and Flintoff’s Ashes in 2005. Stokes’s Ashes in 2019? Don’t bet against it.

THE TIMES

All through the years of dominance, a generation of Australian cricketers would complain that, during rain breaks, the only highlights reel that would be shown on English television was Headingley 1981, the miracle as was.