The world No 1 found himself at the centre of another storm on Monday, with shock jocks piling on the scorn in the increasingly political battle surrounding the Open.

With the public confused as to why tennis players are in Melbourne in the midst of a pandemic when Australians are stranded overseas and Victorians interstate, Djokovic and company are an easy target.

But one man’s demands, as the debate surrounding his appeal on behalf of his peers has been framed in some quarters, are another’s requests.

At least one of the entreaties is tone-deaf in the current climate, though it is scarcely the first time an ambit claim has been lodged among other more reasonable demands.

A mansion with a tennis court in Portsea? Sounds lovely. But also ludicrous given the storm that has unfolded over the past 72 hours.

But it did occur at the US Open last year. Djokovic was among those to pay extra for a residence policed by private security. And it was, for a period, also under consideration for the Australian Open.

Tennis Australia boss Craig Tiley is on the record with The Australian as saying it was a possibility being explored at length last September.

Reading the room is important for any leader. And the current controversy has been exacerbated by Djokovic’s propensity for a misstep or worse.

A past brain explosion about vaccination was regrettable at best and closer to unconscionable. The Adria Tour, while conceived as a charity fundraiser, ultimately proved to be a debacle.

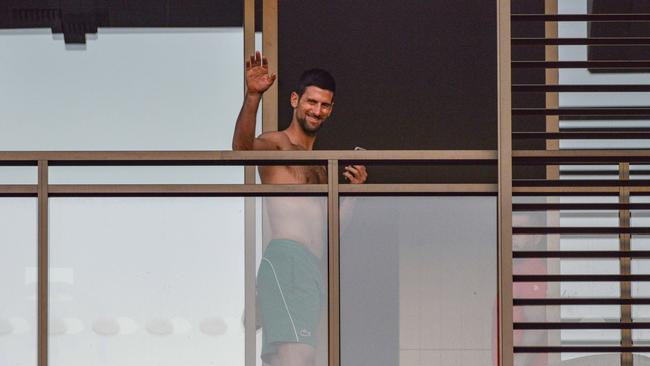

The sight of players dancing shirtless in a nightclub in the midst of a pandemic, with several then testing positive, proved a black eye for the sport and besmirched Djokovic’s reputation.

A couple of the current claims failed the pub test. But despite the vitriolic backlash on Monday, an argument can be made the Serbian is a victim of his position.

Little consideration has been given to the fact the 33-year-old now has a broader role than simply trying to extend his remarkable record at Melbourne Park next month.

The 17-time major champion is the leader of a new organisation called the Professional Tennis Players Association.

It came to life in New York in August amid acrimony. The eight-time Australian Open champion was forced to abandon his post as the ATP Players Council president amid recriminations.

While the PTPA policy positions are not yet entirely clear, the aspirations are. The body stands for the betterment of tennis players.

With 72 professional players now enduring strict quarantine as a result of positive tests on three flights to Melbourne, the angst felt by some of those parties has been very public.

Discussions have been occurring regularly behind closed doors for players confused, rightly or wrongly, by the plight they find themselves in.

Messages have been flying between parties quicker than Tennys Sandgren’s Twitter fingers. Tennis Australia has held regular briefings about the fraught situation.

Representatives of both the ATP and WTA Tours have also been lobbying officials to improve the conditions of those locked down while their peers practise.

Better food, training equipment and other improvements are their aims. Sound familiar? They were also among the requests made by Djokovic to Tiley.

Surely the PTPA needed to make a representation on behalf of the players, even if a couple of those requests were over the top. Negotiations start somewhere.

The position of any leader of an organisation, be it a business lobbying group, a union or a political party, would be in peril if they did not represent the interests of their members.

That is the lot of Djokovic now as the frontman of the fledgling organisation.

And if he is to become a leader of distinction for his peers amid a changing landscape for tennis in coming years, it will not be the only time he bears the brunt of a brutal backlash.

When it comes to polarising the public debate, there is no bigger name in men’s tennis than the Australian Open king Novak Djokovic.