How Lleyton Hewitt helped turn Roger Federer into the best

Roger Federer is a global phenomenon but, as a new book explains, Australia and Lleyton Hewitt played an influential role in helping shape the star.

Roger Federer’s legend as an athlete of global renown is complete but Australia sits high among the nations to have had a huge influence on one of the greatest of careers.

With his 40th birthday last Sunday, Federer is harnessing his expertise from the past three decades in a bid to compete in a historically significant US Open beginning on August 30.

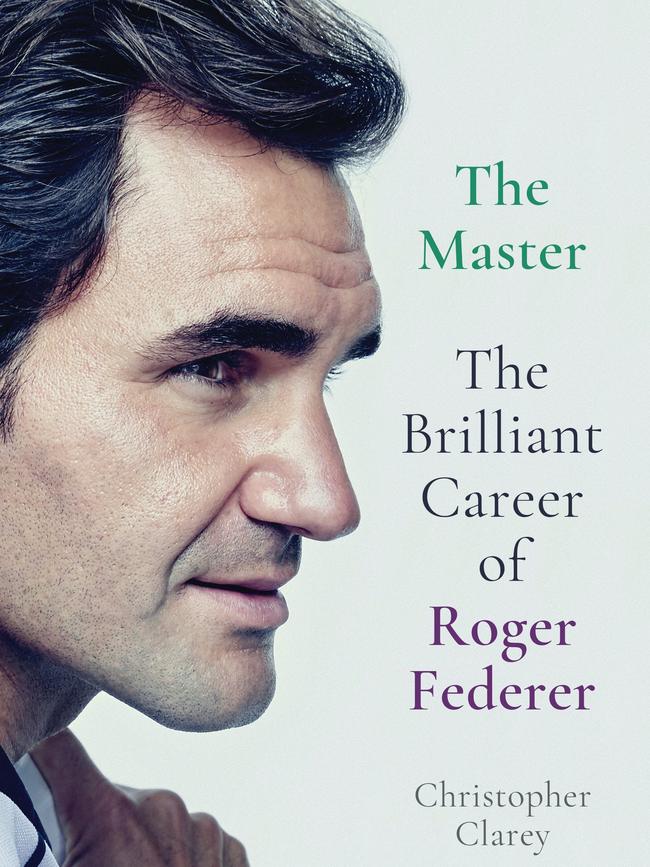

The milestones coincide with the publication of an authoritative examination of the people, circumstances and processes that have driven the Swiss to superstardom.

Written by acclaimed American journalist Christopher Clarey, who has had remarkable access to Federer for more than two decades, the level of detail it provides is exceptional.

Despite the magnitude of words written about him, The Master; The Brilliant Career of Roger Federer offers an examination and context that will captivate readers beyond the sport.

The on-the-record involvement of critical figures who helped Federer form himself from a young age, and steer him through moments of difficulty, is a significant bonus, for those who have coached him have always respected his privacy.

So, too, the engagement of tour figures including the enigmatic Russian Marat Safin and Andy Roddick, to Australian coach Darren Cahill, in the project given their insight and expertise.

And the detailed essays on his legendary peers Rafael Nadal and Novak Djokovic are highly enlightening, even for those with an invested interest in the sport for many years.

Federer was aware of the project but, Clarey said, kept at arm's length because “he did not want to be handcuffed in any way” to preserve the book’s independence.

“My goal with this, well, you don’t know what he is going to do, but I think his main body of work is done and that is why the timing is right for me,” Clarey told The Weekend Australian.

“I felt like there was this energy, this goodwill towards him, but I did not want to celebrate him. That is not my goal.

“I wanted to commemorate his career and the way I saw it through my filter, having had all that crazy access over time.

“I’m hoping to try to hit tennis nerds … but also trying to hit people who don’t necessarily know a lot about tennis but would be interested in Roger in a general way.”

Arguably the most important influences on Federer’s life have been Australian Peter Carter, an early coach who died in tragic circumstances in 2002, his wife Mirka Federer (nee Vavrinec) who he first kissed at the Sydney Olympics, and physical trainer Pierre Paganini.

Given Federer’s longevity, there is a wealth of experiences to explore.

But the Australian connection, which features heavily in the first half of the book, make the book worth the purchase alone for those from here. His Australian Open triumph in 2017 might be the finest of his career.

The extraordinary influence of Carter, who died tragically on his honeymoon in South Africa in 2002, and his junior rival and peer Lleyton Hewitt feature at great length.

As Clarey notes, just as Federer’s dominance inspired Nadal and then Djokovic to raise the level of their own excellence to produce one of sports great rivalries, Hewitt did similarly to the Swiss.

“Peter Carter, because of his connections to Australia, he had access to people like Cahill, he had access to Hewitt, who I think was a touchstone for him,” Clarey said.

“I think the Hewitt rivalry has been lost in the sands of time. It was a very important one for Roger. Roger used him as his measuring stick, much as Rafa and Novak used Federer as their measuring stick later on.

“I think the fact they had such a significant rivalry as juniors — Cahill talks about that match all the time in Switzerland when they were both losing their minds — so I think Lleyton is pivotal.

“I think that match that he lost in Melbourne in the Davis Cup, which could have crushed him given how sensitive he is, it instead proved a building block and gave him further motivation. Lleyton was huge for him, for sure.”

The sensitivity and emotional investment of Federer is a thread throughout his career.

The 2003 Davis Cup semi-final, where Hewitt overcame a two set and 3-5 deficit against the reigning Wimbledon champion to prevail, left the Swiss desolate at his inability to honour Carter with a victory on Australian soil. But Clarey notes he has an incredible ability to move on swiftly after an emotional burst or low.

And that even as a remarkable professional, Federer took time to embrace the high and low points of his career with teammates, which included some very good nights out.

In that spirit, one of this journalist’s favourite memories occurred the night of that Davis Cup loss and has not yet been told in print. What better time than now?

Federer washed away the disappointment with his teammates at a nightclub in Melbourne’s casino.

This writer, having attended the semi-final strictly as a fan and incentivised by Hewitt’s triumph and too many celebratory beers, headed there by chance.

It was a surreal scene. Federer was the Wimbledon champion. But his triumph was so new that no one except the tennis fans in attendance recognised him.

The Swiss team had snuck in a large bottle of orange juice, no doubt topped up with spirits, and were having a ball. Teammate Marc Rosset was all facial hair and beer.

Another member struck up a conversation with my then partner — she certainly would have enjoyed better seats at Wimbledon given he boasted a recent success over Pete Sampras at the All England Club.

And Federer danced away by himself, at one stage bopping up and down against a wall with merriment, before later signing a Wimbledon T-shirt another friend was wearing.

The Swiss was devastated by his defeat. But he remained genial, grounded and obliging afterwards, which is a constant theme that runs throughout the book and across his celebrated career.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout