Australian Open 2019: Why Rafael Nadal has become a wrecking ball

Rafael Nadal has discovered one of the richest veins of form of his entire tennis career by moving the fight to the front of the point

It looks like the beginning, but it’s already the end.

Rafael Nadal has discovered one of the richest veins of form of his entire tennis career in Melbourne the past fortnight by moving the fight to the front of the point instead of the back.

No more prolonged, grinding, gut-wrenching, lactic-acid inducing rallies from the trenches deep behind the baseline. No more wearing out opponents and wearing himself out in the process.

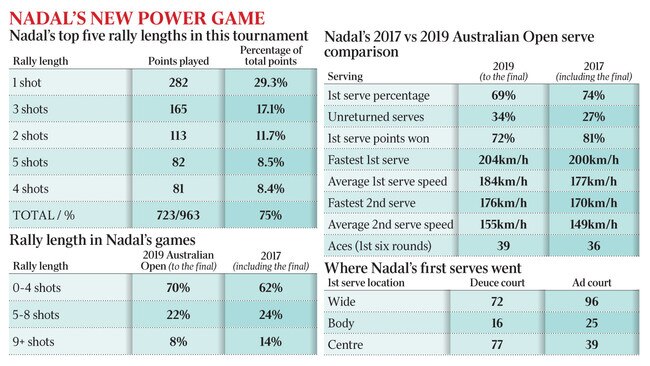

Thirteen-shot rallies have been cleverly replaced with three-shot rallies. He has upgraded his hard-court strategy and has subsequently been a wrecking ball through the bottom half of the draw for the past two weeks en route to Sunday’s final. He has won 12 out of 18 sets by a scoreline of 6-3 or better.

How is he doing it? By upping his aggression at the start of a point. By striking first and making his opponents’ heads spin.

Nadal’s semi-final opponent, Stefanos Tsitsipas, didn’t know what hit him. “It felt like a different dimension of tennis completely,” Tsitsipas said afterwards. “He gives you no rhythm. He plays just a different game style than the rest of the players. He has this, I don’t know, talent that no other player has. I’ve never seen a player have this. He makes you play bad.”

Tsitsipas craved rhythm and got none. The average rally length for the match was 3.9 shots — that’s barely two shots for each player, and that’s right in Nadal’s new wheelhouse.

Nadal stood on the other side of the net from Tsitsipas for an hour and 46 minutes, and Tsitsipas never came close to figuring him out, losing 6-2 6-4 6-0.

To join the dots and understand what type of superhuman tennis player Nadal has morphed himself into to begin 2019, you have got to turn to a stats sheet.

Nadal has played 963 points to get to the final, with a rally length of just one shot being his most abundant. Our minds remember the longer rallies, where Nadal runs side to side, showcasing his amazing defence, while we quickly dismiss the shorter rallies, incorrectly assuming players messed up trying to get the point started.

One-shot rallies are where Nadal is thriving this year. Rally length is defined by the ball landing in the court — not actually being struck by a racquet. So even though the serve went in and the return may have been hit into the net, it is recorded as a one-shot rally as just one shot went in the court. The top five rally lengths that Nadal has played in this tournament are one to five. The reason a three-shot rally is more abundant than a two-shot rally is the halo effect of the serve, making the third shot of the rally (serve +1) an easier ball to finish with than a return of serve.

Nadal has forged a +30 (156-126) advantage in one-shot rallies, and a +19 (92-73) advantage in three-shot rallies.

Nadal is making fewer first serves — which is a good thing. The first serve has two conflicting elements — power and consistency. You want to get the serve in, but you also want to hit it hard, which means more faults. Nadal has previously gone for more in the court at a lower speed, but not this year. He has simplified his serve motion and is hitting with more velocity as a result.

Nadal’s favourite serve in the deuce court is typically slicing down the T, but he has hit almost the same number out wide, looking to catch all six right-handed opponents he has played moving early to their left looking for the lefty first serve down the centre.

In the ad court, his big weapon has always been the lefty “can-opener” out wide, and he is hitting it more than twice as much as either of the other two locations.

Playing fewer long rallies means Nadal’s muscles and his mind are much fresher going into the final. More than half of all points Nadal has won in this tournament have required him to hit a maximum of just two shots in the court. Not a lot of wear and tear on the body with that game style.

In 2017, he had won just 52 points more than he had lost (580 won/528 lost) in the crucial 0-4 shot rally length, but that has risen this year to a 108-point advantage (391/283) in short rallies.

Nadal has done his homework. He clearly sees where he needs to focus his attention to craft the biggest advantage in points won and lost. Overall, the longer the point goes the more even it becomes, which explains why Nadal is overwhelming opponents a lot more in shorter rallies than long ones.

At 32 years of age, Nadal is once again tinkering with his strategic recipe, slightly modifying and upgrading the ingredients necessary to take the major titles. “Today I have to adapt my game to the new time and to my age,” Nadal said.

We can see Nadal’s improvement both on the court and on a stats sheet. Shorter rallies are more important to winning matches than longer ones because of their overwhelming abundance. Nadal’s commitment to play with more power and urgency at the start of the point has him in prime position to triumph again in Melbourne.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout