Rugby: James O’Connor’s journey to jail cell hell and back

James O’Connor was drinking ‘to get numb’. Huddled, freezing in a Paris jail cell in 2017, the Wallabies ace started to realise he had to turn his life around.

James O’Connor had never felt fear like it. It overcame his body as he huddled in the freezing, dark jail cell as he watched the wretched chaos unfold around him.

He saw one man smear faeces across their cell wall and another scream in rage. He then watched another inmate strike the screaming man in the back of the head and “drop him” to the floor.

For two nights in 2017, O’Connor languished, frightened, in that Paris cell. He shared a thin blanket, one mattress, with three men in torrid, stinking conditions.

“My time in there haunted me,” O’Connor says. “It felt like a medieval dungeon. It was horrible.”

He was thrown in this cell because he was standing beside fellow rugby player Ali Williams, who was buying cocaine near a Paris nightclub and was busted by police. O’Connor was never charged and was exonerated of any wrongdoing.

O’Connor walked out of that jail hell hole and into the Parisian morning light thinking: “OK, shit, I actually need help.’’ But the help he needed was another year away.

Instead he continued to live his life “minute to minute”. He loathed rugby, his body was in constant pain and his ego was out of control. He numbed all that physical and emotional pain with prescription drugs and boozy nights out.

It would take another year before he would figure out “his purpose” and finally find the love of the game — and life — again.

Today, O’Connor has just drenched himself in a waterfall in the Gold Coast hinterland when he sits down and says he wants to talk about the past. The 30-year-old is happy to bare his soul. He is, by his own admission, a transformed man, likely to be found doing yoga on a Sunday morning before he hits the farmers’ markets.

O’Connor wants to speak about his worst of times in the hope it will help someone else through any kind of darkness they might be suffering.

He says he is a living example of how someone who was “very lost” can be found.

But really, how did O’Connor lose his way?

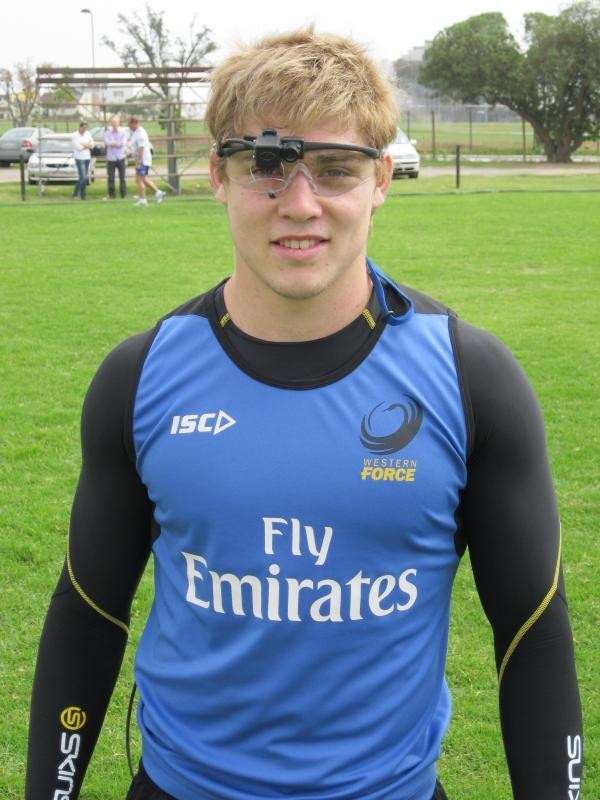

In the beginning, it seemed like he was living some kind of rugby fairytale. Back in 2008 he became the youngest ever footballer to play Super Rugby. He was touted as a “once in a generation” player and he felt no pressure.

The teen played for the pure love of the game. He earned $15,000 a year on a rugby scholarship, ate Nando’s most days and rode his scooter to the beach in between training sessions. He paid $50 a week in rent, living with two other boys, in a “dump” of a house overlooking the Indian Ocean. If they cooked, it was “butter chicken from a can” once every two weeks, otherwise it was takeaway.

“We played video games every night to see who would have to shout dinner,” O’Connor said. “We were loving life and rugby.”

Within months, at 18, he was on a spring tour with the Wallabies in Europe. “It was unreal,” O’Connor says.

Life rolled on and up for O’Connor from that European tour onwards.

At 19, the exceptional talent began making serious cash with a contract in the millions at the Western Force, his fame growing, his ego growing. He would turn up to restaurants, go to pay the bill and find it was already paid for. At nightclubs it was free drinks all night. There were women, and more women. It was a loose and wild ride.

“I was always chasing pleasure,” O’Connor says. “I had never seen money like it. Then every door started opening for me. I would go to a restaurant and there would be no bill. Your ego kicks in. You think you are untouchable.

“It became no longer about the rugby, or about the purity of the craft. It becomes about after the game. You play well, so afterwards you will get noticed … what drove me to play football as a young man, to simply be the best, started to dissipate. The lines got skewed.”

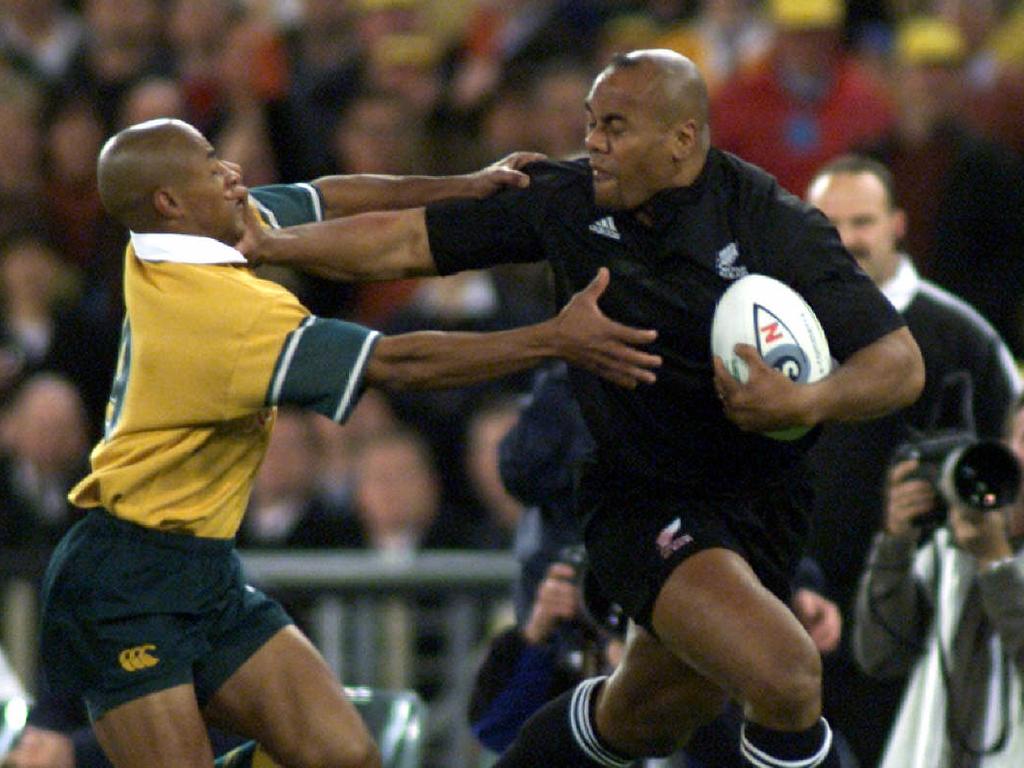

Still his career got stronger, his football better. He made the Rugby World Cup team in 2011, nailing a decisive 72nd-minute penalty against South Africa to clinch the Wallabies a semi-final tie with the All Blacks.

“I thought we were going to win the World Cup. Obviously the All Blacks wiped us out in the semis,” O’Connor says. “And after that, I was like, ‘I have almost done everything, what more is there? Where’s the excitement now?’”

Off the field, he had started partying, missing the bus to Wallabies training and so on, “bad-boying” life here and there.

But in hindsight a bigger mistake came when he switched from the Force to the Rebels. “It never clicked,” O’Connor says. “The rugby style they were playing, I knew from the start that I had made a mistake.”

He’d gone from running the backline at the Force, to having the Rebels captain Stirling Mortlock having the final say (naturally). “And that didn’t sit too well with me at the time,” O’Connor says. O’Connor acknowledged he could be quite the “little shit” when he was at Melbourne.

“I think people possibly thought I had turned into a little brat,” O’Connor says. “I just didn’t have the intellect to communicate my feelings at this stage of my life. I didn’t know how to have an open conversation with someone. I thought if you don’t see it my way, then you are not on my side.”

At the Rebels, he didn’t train as hard. In games he was a step off in his tackles. He felt fatigue. His body started breaking, there were hamstring and ankle injuries, he suffered a shocking injury to his liver. His mind was tired. He was on a “cocktail” of anti-inflammatories, penicillin (after he lost his spleen in an accident at 15) and sleeping tablets to come down from the highs of a game.

“Physically my body was deteriorating, I was still a powerful, young man, but I wasn’t as powerful as what I had known my whole life,” O’Connor says. “I was angry, frustrated, I wasn’t performing, people were coming down on me. I couldn’t get away with what I was before. It felt like the walls were coming in on me. That’s when I started becoming … a bit darker.”

By 2013, rugby had become a chore. “And I had started lying to myself,” he says. “I started to pretend I didn’t care that I couldn’t play as well.” He told people around him he just wanted to go overseas to play to experience the French lifestyle.

“But really it hurt that I couldn’t perform here,” O’Connor said. “I knew Melbourne didn’t want me. I didn’t want to be there. I was going to sign back with the Force but then I ended up getting drunk at an airport, there was an incident, I hid, I tried to let it blow over, it didn’t and Australian rugby were like: ‘You go do you for a bit’.”

At the age of 23 — with 44 Wallabies caps — spiritually and physically broken, he headed to Toulon. Life didn’t get better from there.

“It got worse,” O’Connor says. “Australian rugby held me accountable to turning up, but as soon as I left, there was nothing left to strive for, without the Wallabies. I didn’t love rugby any more. I was just doing a couple of good things in each game, here and there to feed my ego. Enough for people to say; ‘yeah, he’s still got it’, but there was no passion in it any more.”

“There was no big low, the whole thing was a low. I was just at the point where every element of my life was breaking down. It was almost like my soul was crying.”

Off the field he was “attracting negativity”. He drank too often because when he was sober he felt how weak he was. “People go out to have a good time, I was doing it to get numb,” he said. “I hated the version of who I had become, I had no discipline, no accountability, my mind was weak. I drank to numb myself. I had no purpose. I was just drifting along.”

Then came that horrid night in the Paris jail cell, and that had him thinking, “right that’s my career done”.

“I was there, I wasn’t caught with anything on me, but I was still living that life of going out and making the wrong decisions,” O’Connor says.

A few months after being locked up, in 2017, he came across “Ollie” from men’s wellbeing organisation Saviour World via a mutual friend. It wasn’t until he was released from Toulon and went to the English Premiership club Sale Sharks that he properly connected with Oliver, who helped him find “true” meaning in his life via the program Saviour World.

Firstly, Ollie told him to bin the cocktail of prescription drugs he was on. “My entire body bloated in reaction, all the toxins move to your fat, I was literally, ‘what is happening to me?’” he says.

In the Saviour World curriculum there are “nine specific practices for each of the physical body mind and soul”.

“Everything builds from that,” O’Connor says. He built his body up to be strong first, starting with intermittent fasting, a wholefoods diet and limiting his caffeine intake — alcohol was out.

“He broke me physically first, then we started again, and then he broke me mentally, to get rid of that sooky kid that would feel like everyone is against him,” he says. “The process we went through was a completely different world, it blew me away, then I just felt so good.”

He started “getting powerful”, picked up yoga, meditation, learnt Kundalini breathing and importantly he found his purpose.

Which is? Aside from playing for the love of the game, it’s to inspire others.

“I also want to use my rugby to inspire people, playing the way I play, on instinct and no stress,” O’Connor says. “Also I want people to see: ‘He was in the dumps, he was partying’. Everyone knows there were 20 headlines of me doing the wrong thing, but if you put that energy into something good you can do something good with it. My good work is playing good rugby, but also helping others with this platform.”

Six years after being expelled by the game in Australia, he was welcomed back into the Reds, then sensationally the Wallabies and there’s hope of another contract in the future. O’Connor has played 52 Tests for Australia, of which he has started 41 — he is confident there is more he can achieve from here.

“When I stopped living just for myself, doors started opening,” he says. “My message to people is it’s important you find your purpose and try to live for something bigger than the ‘I’. He adds: “Play the real game.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout