Patient zero: the Wallaby who couldn’t live with the noise leaves a ‘quiet legacy’

Dan Vickerman’s mind had become a war zone and he didn’t know why. A once measured, ‘gentle giant’, there were now times when he’d lose it over the smallest of things. His mother reveals why she believes rugby may have cost him his life.

In the middle of the night, when “demons” were raging in Dan Vickerman’s head, he’d call his grandmother, Erna, and her sage words would calm his mind.

Severe insomnia plagued the former Wallaby, but the conversations with his grandmother, who lived in Cape Town, would help fight off the dark thoughts.

In the final years of his life, Dan’s mind had become a war zone and he didn’t know why. A once measured, “gentle giant”, there were now times when he’d lose it over the smallest of things. His mother, Val, remembers his moods swinging between incredible anxiety to utter depression.

A few months before he took his life, on the morning of February 18, 2017, Dan bluntly told a friend: “My head is f..ked.” He left behind a wife, Sarah, and two beautiful boys. On that summer morning, Val received a phone call telling her that her only child had died. He was 37.

In the dark, numb days that followed, nothing made sense and in the midst of grief, Val, a pragmatic, stoic woman, went searching for answers. When someone dies by suicide there are so many unanswered questions for those left behind, starting with: “Why didn’t I ...?”

“There is also an incredible amount of guilt. So you go looking for answers,” she says.

While researching suicide in sport and personality changes, Val came across chronic traumatic encephalopathy. She had never heard of it. CTE is a brain disease linked to repetitive head knocks. The more Val learnt by reading research papers from Boston University’s CTE Centre and Brain Bank, the more it became clear that her son, who had a three-decade rugby career that included 63 Wallabies Tests, had been suffering from the condition. As Val says, “his brain was sick”.

At Val and husband Les’s home in Bowral, NSW, she sits in a plush armchair in their formal living room, pulls out a sheet of paper and starts reeling off CTE symptoms that related to her son.

“He had mood and behavioural changes in his later years; he had exaggerated responses to day-to-day stresses; anger and agitation due to inconsequential happenings; mood fluctuations; depression; anxiety; generalised body aches and pain; and severe insomnia,” she says.

Val believes Dan knew things “weren’t right”. “He went to a psychologist, he went to [another] psychiatrist, and not one of them said it could be CTE,” she says. “It was not really out there back then.” It was a time when there was little understanding of the disease, which has since been found, post-mortem, in the brain tissue of several leading Australian footballers, including St Kilda’s Danny Frawley and rugby league player and coach Paul Green. Both took their own lives.

But what sets apart Dan Vickerman – a domineering lock whose international career ran from 2002 to 2011 and who had three seasons with the Brumbies and five with the Waratahs – is that he was patient zero for the Australian Sports Brain Bank.

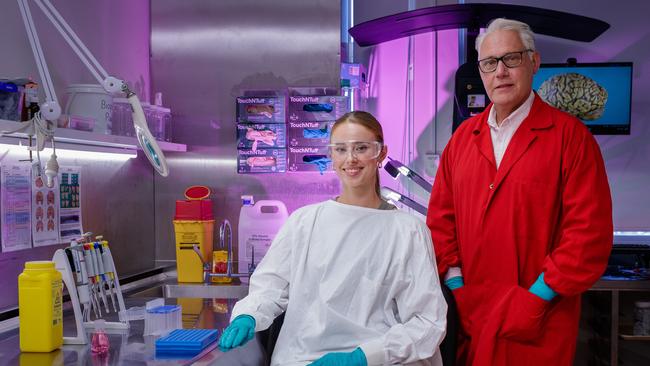

Michael Buckland, the chief neuropathologist of the Australian Sports Brain Bank, says Dan’s death led to its formation. It is a joint initiative by the neuropathology department at Royal Prince Alfred Hospital in Sydney and the Brain and Mind Centre at the University of Sydney.

“I was very aware of Dan’s death, he used to play for Sydney Uni, so his passing was very local to us as well,” Dr Buckland says. “The fact his brain was unable to be examined was really the driving force, the motivation for setting up the Australian Sports Brain Bank. We wanted a pathway for families to have their loved ones examined, if they so wanted.

“After we launched the brain bank in March 2018, Val and Les Vickerman were in contact immediately.”

Not long after the Australian Sports Brain Bank opened, Val and Les travelled up to Sydney and met with Dr Buckland, with that interaction confirming their thoughts on Dan’s condition.

Soon after Dan’s death, the Rotary Club of Bowral/Mittagong suggested establishing the Dan Vickerman Scholarship for PhD students in conjunction with Australian Rotary Health.

The criteria for the scholarship was specific to CTE research and it was to be undertaken at the University of Sydney. Covid intervened and it was only this year that the scholarship has been awarded. Young scientist Joanna New is the first scholarship recipient. “Being awarded the Dan Vickerman Scholarship is a great honour to me, it holds to his legacy, his story and it allows him to be an example within not only the research community but the sports community,” Ms New says.

“My work is really about trying to address some of the unanswered questions in the CTE space. Practically what we hope to develop with this research is to help find a test that can be used in a medical or sporting setting.”

Val has said Dan may have “had a chance” if he had known what was happening inside his head, and life may have played out differently.

“Hopefully with the research we will one day be able to diagnose CTE in life,” Val says.

“If people are able to get a definitive diagnosis, even if there is no cure for it now, they will at least feel ‘I am not going mad’.

“There is a reason for it. I think it will make it easier for the family. They will have an understanding of what is happening. I think for the children of people that take their own lives, who may ask, ‘Why did my dad leave me? Why did my mum leave me? Did they not love me enough?’ I think if there’s an answer for the children, it may make things easier.”

Career on the rise

As a child, Dan loved the “crash and bash” of rugby union. He adored the contact and, being tall, he soon found himself playing in the second row.

He played for the prestigious Bishops Diocesan College in Cape Town, which has produced many great Springbok players, and he proudly wore the jumper.

“For some unknown reason, the Bishops rugby jumpers were white. The school was located at the lee of Table Mountain, where it rained all winter,” Val says, laughing. “Dan and the jumper would always come home absolutely covered in mud. He loved sports. He aspired to be in the school’s firsts rugby team, which he did.”

While mild mannered off it, on the field Dan was brutally competitive and he had big dreams. In a private moment, a teenage Dan told his father: “I want to be the best lock in the world.” With a link to Australia via Les’s father Leslie, he travelled to Brisbane in 1999.

“After school he played for the Queensland University, then after that he went back to South Africa and played for the South Africa U21 Baby Bok team,” Val says.

While initially he had hoped to become a Springbok, his journey back to Australia in 2000 would make him a Wallaby.

While attending Varsity College and the University of South Africa, Dan was lured to the Harbour City in that Olympic year to attend the University of Sydney. He was then contracted by the Brumbies Super Rugby franchise. His selection for Australia “A” sealed his future allegiance and he soon made his Test debut against France in Sydney.

Dan would end up playing in three World Cup campaigns before his retirement from the game in 2012.

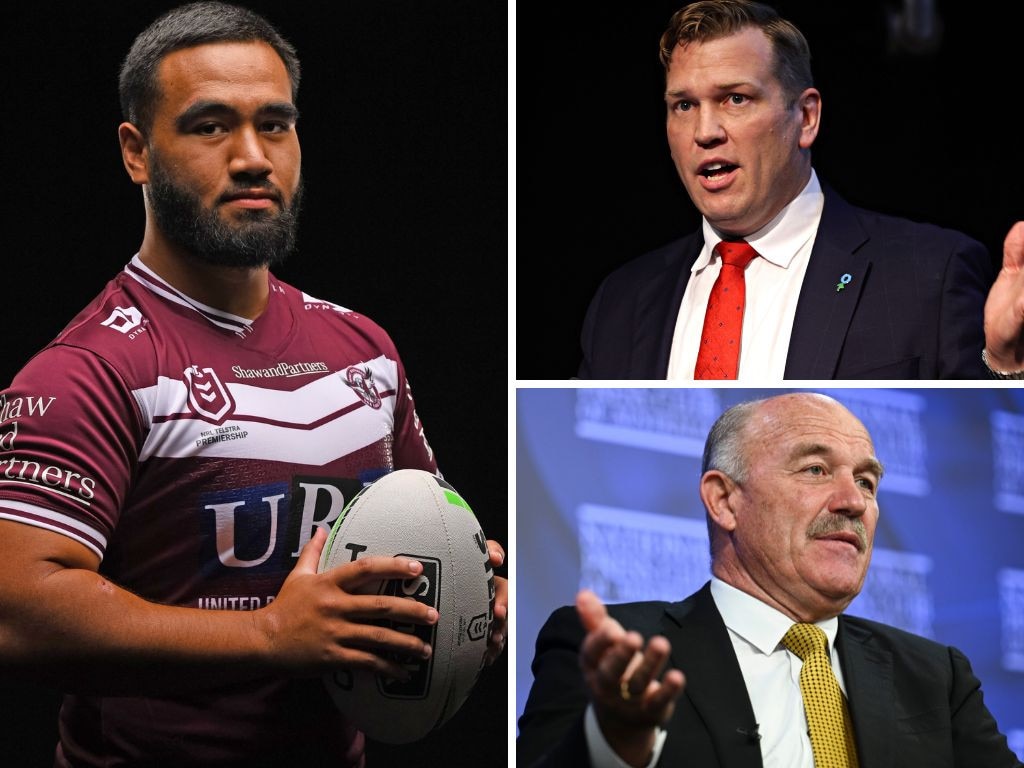

“He was very uncompromising in battle,” his Tahs and Wallaby teammate – and now Rugby Australia chief executive – Phil Waugh said.

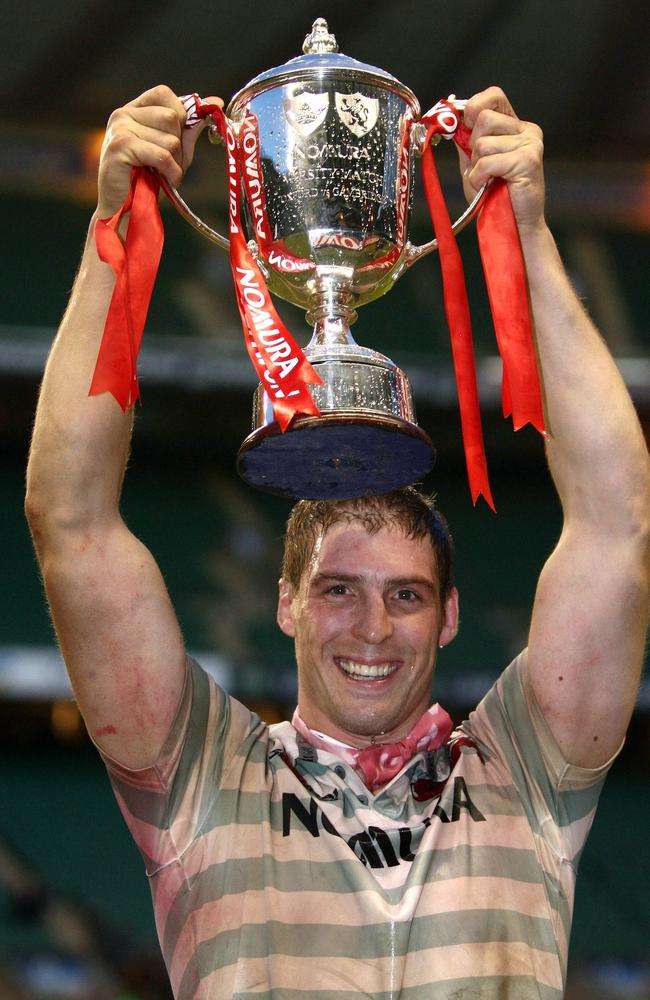

After playing at the World Cup in 2007, he withdrew from the Australian rugby scene and headed to England for three years. At Cambridge University he earned a masters in land economics and, in another sparkling moment in his rugby career, Dan captained Cambridge to a 31-27 victory over fierce rivals Oxford in 2009.

It was, by any measure, a glorious career. “He loved the game,” Val says.

Suicide links

To Val’s knowledge, Dan was never knocked out or diagnosed with concussion while playing rugby union.

Research by Boston University’s CTE Centre and Brain Bank shows CTE is caused by repetitive brain trauma. That trauma includes both concussions that cause symptoms and non-concussive hits to the head that do not cause symptoms.

Boston University says the number or type of hits to the head needed to trigger degenerative changes in the brain is unknown.

But what is known is that suicidality has been clinically found to be associated with CTE, Dr Buckland says.

“There’s a very strong and disturbing association between CTE and suicidal behaviour, including suicidal ideation and completed suicides,” he says.

“We are finding that in our cohort – and the Boston University group have also reported that in their cohort – the majority of people with CTE, they either self-report or their family members report suicidal ideation or suicide attempts. Suicide is certainly over-represented in the CTE cases compared to those cases without CTE.

“About just under half our cases, our donors with CTE, ended with us because they suicided.”

Just two years after Dan’s death, Australian rules footballer Danny Frawley was found to have had CTE after he deliberately crashed his car into a tree in country Victoria.

In 2020, Richmond player Shane Tuck endured a “war zone in his head” before he took his life at 38. He had CTE.

In August 2022, former Cronulla player and Cowboys coach Paul Green, 49, who’d celebrated his son’s 10th birthday the previous day and was tossing up several job offers, took his own life. He was found to have had stage-three CTE. In November 2022, AFLW player Heather Anderson died by suicide. She was 28. Anderson, played rugby league and then Australian rules, from the age of five. She too was found to have had CTE.

Dan was part of the Wallabies team who were runners-up in the 2003 World Cup final against England. The mind battles of those English rugby champions have been well documented.

Last year England World Cup player Steve Thompson said he often couldn’t remember the names of his children and had no memories of the 2003 victory. “I can’t even remember being in Australia,” he has said. Thompson, 46, has also said his shock early-onset dementia diagnosis left him feeling suicidal.

So many questions

Val is an advocate for suicide prevention awareness and continues to run a suicide support group in Bowral in an effort to help those, like her, who have lost a loved one.

A common conversation can be around the “sliding doors” moments. For her, it involves her mother, Erna, who passed away two months before Dan took his life. Val wonders if her mother had been there for another desperate phone call, maybe she could have helped him with his tormented thoughts that night.

“There are many should have, could have, what ifs, you ask yourself when someone suicides,” Val says. “And I wonder if my mother had been alive…”

Dan’s hulking frame still looms beautifully large in his parents’ home. He’s there, grinning gently in his Wallabies jersey, walking off the field, forehead bleeding. A local painter, Dave Thomas, has captured this warm, joyous moment, which the Vickermans proudly have hanging on their wall.

“We hope to donate the painting to Sydney University Rugby Club,” Val says. It’s another institution where Dan left a strong legacy, playing 49 games, including three grand finals.

But it’s the memories off the field that shine through the most on this visit to Bowral. Les and Val show a 2016 photobook, capturing an extended family holiday adventure to Cape Town.

Everyone is smiling as they stand in the front of the house where Dan was raised. There are pictures on the beach where he swam and played as a child.

They are all carefree, windswept, happy – it was just months before Dan died. The photos show no hint of what he was battling.

‘Real’ ambition

After Dan passed away there were newspaper and TV reports about athletes suffering post-retirement – insinuating that the former Wallaby was troubled by no longer playing the game – but Val makes it clear, her son’s mental anguish wasn’t related to his sporting career coming to an end.

“No, that’s not true,” she says. “Dan actually had prepared for a career after rugby.”

He had worked for KPMG, then in property and just weeks before he died he had announced that he had set up a property investment fund. His career trajectory was on the up.

But for those close to him, it was clear Dan also had other priorities.

Les recalls turning to his son, after Dan had not long retired from rugby, and asking what his “real” ambition in life was now. “To be the best father in the world,” Dan said.

Val wants the world to remember her son as a “gentle giant”.

“He was an unassuming person that didn’t want the limelight, didn’t court the media … and now he is leaving a quiet legacy,” she says.

If you or someone you know may be at risk of suicide, call Lifeline (13 11 14) or the Suicide Call Back Service (1300 659 467), or see a doctor

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout