The Test batriarchy has been overthrown

Batting averages are dropping in Test cricket and T20s are not solely to blame.

Words such as ‘even’, ‘tense’ and ‘competitive’ have been applied to describing the first Test in Adelaide. But perhaps the most literally accurate description is: ‘average’.

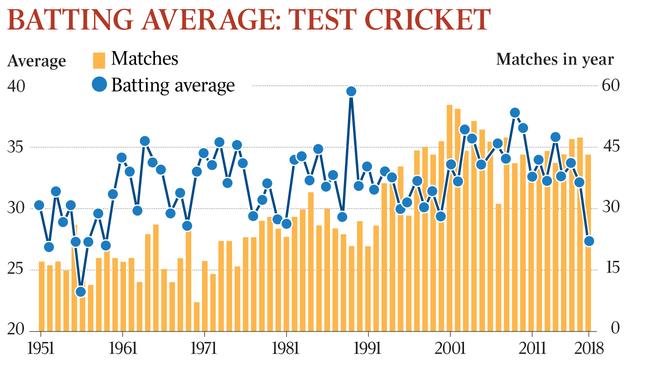

In four innings, Australia and India accumulated 1083 runs, or 27.1 runs per wicket — a near-perfect match for the 27.3 runs per wicket in the calendar year’s other 42 Tests.

Not since 1959 has this per capita rate been so poor, which seems remarkable in view of the many advantages modern batsmen enjoy, from the quality of their equipment, including more powerful bats and lighter protective gear, to their rich financial rewards and ample preparatory resources.

Nor does it seem so long since we were pronouncing the general hegemony of the bat. With the turn of the century, batting seemed to achieve a new stability of productivity, with a floor in the mid-30s, and peaks over 50.

Some of us wondered, in fact, whether the bloated scores were all to the good. Ten years ago, when averages were a third greater than they are now, more than a third of all Tests were drawn. This year only four Tests in 43 have ended in stalemate.

This proceeds in parallel with a contrasting observable reality, that, with the spread of T20, batting today is more dynamic, the players stronger, more versatile, more innovative. Mike Atherton, who has observed many of the greatest and at close quarters, thinks Virat Kohli the best batsman he has seen.

So what underlies this seeming overthrow of the batriarchy, at least in general and quantitative terms?

Could it be the bowling? Probably not — after all, the personnel has hardly changed year-on-year.

Could it be the pitches? Maybe — the tendency of countries to roll out surfaces tailored to their own bowling advantage is widely remarked on.

Could it be practice methods? Some complain of the substitution of the empty calories of throwdowns for nutritious net practice, partly because of the workload restrictions on bowlers, although also because of the growing preference for preparation being about feeling ‘confident’ rather than actively challenged or problem solving.

Perhaps the simplest explanation — it’s so simple as to sound axiomatic, but bear with me — is that there aren’t as many top-class Test batsmen around.

In the period 2012-2015, there was a quite extraordinary twilight of the idols, perhaps unprecedented: Sachin Tendulkar, Rahul Dravid, VVS Laxman, Virender Sehwag, Kumar Sangakkara, Mahela Jayawardene, Tillekeratne Dilshan, Shivnarine Chanderpaul, Jacques Kallis, Graeme Smith, Kevin Pietersen, Ricky Ponting, Michael Clarke and Mike Hussey all bid farewell to Test cricket, the majority in favour of a few extra years of T20.

To this list has since been added the likes of AB de Villiers, Alastair Cook and Younis Khan, reinforced by the involuntary ineligibility of Steve Smith and David Warner. Among Test cricket’s top 30 run scorers, only one current player remains: Hashim Amla.

Even if seldom in such profusion, of course, players are always retiring. But what’s happened, one suspects, is that a fresh generation of Test talent has failed to emerge. In Adelaide, Cheteshwar Pujara became the 96th player to make 5000 Test runs, but he is one of only seven with that many who are currently active and available.

Why have successors to that gilded generation not emerged? It seems obvious to observe, again, that the game has changed, but that makes it no less true, and also belies the strain of nostalgia for the good old days when men were men, a ramp was something your drove up, it was only newspapers who had scoops, and everyone averaged 50 in the Sheffield Shield.

First-class cricket, performances in which have always been the most reliably predictive measure of top-level success, is in eclipse, here and everywhere, played in fits and starts, weakened by international calls, debased by high-performance jiggery-pokery.

When Rohit Sharma stepped out at Adelaide, he had not played a first-class match since being dropped from the Indian Test team in February, and frankly it showed — a batsman caught in the deep at 86 in the first innings and caught at silly point at 5-248 in the second is falling between two tall and shaky barstools.

T20, which has supplanted four-day cricket as the game’s most profuse variant, is no training for anything other than itself, technically or temperamentally. The biomechanics of Aaron Finch driving over cover in a T20 and bending his front leg to hit along the ground through cover in a Test match are radically different — as we learned in Adelaide.

Equally suspect is the mentality that sees moving the game on as an end rather than a means.

Four years ago, KL Rahul made a painstaking debut Test century in Sydney over six hours. In Adelaide, like Finch, he presented an intriguing study, flailing away from his body at the top of the first innings, getting away from himself in the second: while KL Jeckyll defended dourly, KL Hyde periodically rose to full height and carved impossible arcs in the air with which he luckily failed to connect.

We should not, however, look too censoriously on this secular shift. After all, the fallibility of the batting in Adelaide made for compulsive viewing. Does anybody seriously regard Matthew Hayden’s 380 against Zimbabwe as batsmanship’s fullest flowering?

Perhaps what we grew used to watching in the noughties was the anomaly — the culmination of a long phase of relative stability, an equipoise between five- and one-day cricket, leading to a bubble economy that fetishised big scores.

This, by contrast, is the first generation that has had to stretch its techniques over three quite distinct games. There is already an underestimated gap between T20 and one-day cricket, which is challenging the likes of Chris Lynn to bridge; Test cricket is exponentially more complicated.

Administrators mandating constant format changing then wondering why batsmen aren’t ‘grinding out big hundreds’ is cricket’s version of cakeism — the expectation fuelled by populist politics that we should not only have cake and eat it too but lose weight at the same time.

This carries entailments, though. Test cricket is a big game. It requires big feats, which build big names, and these have most commonly been accomplished with the bat. Next year’s Ashes commences the first cycle of the new World Test Championship. A championship in which everyone prepares decks to give their own bowlers a chance of taking 20 wickets will soon pall. And an average game will not generate those extraordinary accomplishments that, even if it is only every now and again, Test cricket needs to verify its uniqueness.