High hopes but no high-fives in Tokyo’s low-profile Games

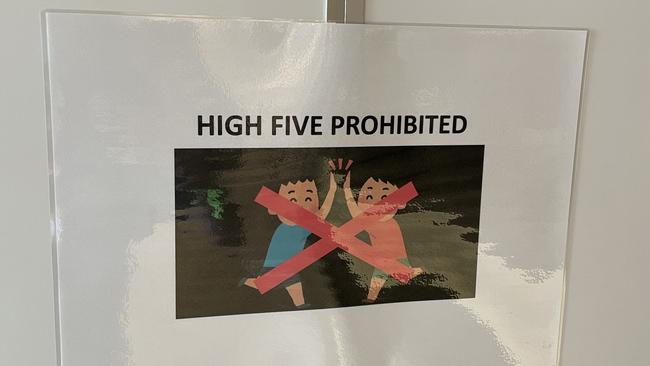

A sign of the times on the wall as hundreds of Australian athletes make their laborious march through health and immigration checks: “High Five Prohibited.”

Tokyo Airport. An A4-sized piece of paper on the wall. Hundreds of Australian athletes sit beneath it on their laborious march through the Japanese government’s health and immigration checks. A sign of the times: “High Five Prohibited.”

The picture is of two stick men looking aghast. The daft buggers are on the verge of laying some skin that could get us all killed, remembering only in the nick of time that such an act of human celebration, kindness and contact is outlawed for the Olympics. Up high, down low, too slow. The stick folk leave each other hanging.

Not that you would have blamed them for failing to realise the Games were even on. The city hardly seems awash with Olympic fervour.

On the drive from the airport to my hotel at Shinjuku, past the sweeping Imperial Palace, where Dawn Fraser once jumped a 2m wall and planned to swim the moat to steal the Emperor’s flag, only to abort the mission when she saw how dirty the water was, I saw no more than three Olympic banners.

On the main street of Shinjuku, a bustling part of Tokyo, I saw one and only one Olympic flag, fluttering in the breeze like it was meant to be on the flag on the 18th green at the Kasumigaseki Country Club, where the world’s least inspiring golf tournament is to take place. It was not much bigger than the sign of the times back at the airport. Most people here think the Games themselves are what should have been prohibited.

Regardless, we push on. The Olympics has survived wars, boycotts, the killing of competitors, doping scandals, internal crises and financial disasters, and now it plans to plough through a global pandemic.

Most of Australia’s team arrived on the weekend, when about 280 athletes and officials dressed in canary yellow arrived from Cairns and duly spent half the night getting through the airport. On Saturday, it took me seven hours to get through customs, a veritable sprint compared to the American reporter who’d been there 19 hours. It was tedious but necessary and the local officials were unfailing friendly.

The dear things. They seemed as confused as us. Got your OCHA app? Where’s your written pledge? We need it in English. And we need it in Japanese. Where’s your doctor’s certificate? Where’s your proof of the jabs? Where’s your letter of invitation? Where’s your accreditation? They were supposed to take our temperature on arrival. No one had a thermometer. It was a such a stop-start process that walking into the sunlight seemed cause for celebration. High-fives all round. Bummer. Prohibited.

By Sunday morning the Australians were all nestled into

an athlete’s village already rocked by a positive COVID-19 case, and with one less athlete than it had before. A Ugandan weightlifter had done a runner, disappearing into the night after leaving a note saying he wanted to live and work in Japan.

Next stop, opening ceremony. Anyone on the Australian team who marches is off his or her rocker. Forget about rubbing shoulders with superhuman athletes. They’re superspreader for all we really know. Tokyo had more than 2000 new Covid cases on the weekend. Not the numbers you want to be getting higher, faster, stronger.

Australia’s team is big. Massive — 472 athletes across 33 sports. But is it any good? That’s the question. Because we want gold medallists. We want re-runs of Ash Barty at Wimbledon. We want reasons to leap from our lounge chairs and holler you little beauty at our television screens while a lump forms in the national throat at the sight of some big-hearted, over-achieving soul from a relatively sparsely populated country like Australia becoming that most golden of athletes, an Olympic champion. He or she will mumble, protest against or fairly belt out the national anthem and we can feel good about the world again.

It’s a mystery how sport and the Olympics can stir us so deeply. The legendary Fanny Blankers-Koen, “The Flying Housewife”, said after dominating the 1948 London Games, “How strange that I’ve made so many people happy.” She’s right on both fronts – it’s strange, yet true.

While we respect every Australian representative, let’s be honest. We will only really remember the winners. Such is sport. So again, is this team any good?

We used to receive pre-Games form guides from the Australian Olympic Committee, but the governing body got the yips after Rio and didn’t want to play anymore. Thirteen gold were predicted for Brazil, only eight eventuated, and everyone thought the useless sods had failed.

AOC chef de mission Ian Chesterman reckons medal projections put too much pressure on the favoured athletes. I think he’s wrong there.

If Jess Fox falls short of winning gold, I don’t think she’ll climb out of her canoe and scream, bloody Chesterman. He put the mock on me. Yet getting him to name a single likely gold medallist is an attempt an extract blood from stone.

“In terms of the number of medals predicted, the AOC did walk away from that after Rio,” Chesterman says. “The feedback from the athletes commission was that it just wasn’t helpful. Athletes put enough pressure on themselves without having us put more pressure on them. I know if we help the sports do their job, we can have great success over there in Tokyo. But we’ve broadened the definition of success.”

Broadened it how?

“By saying yes, we want to win medals, but we also want to help athletes produce personal bests,” he said. “In this environment, that’s a particular emphasis we need to have. It hasn’t been a perfect lead-up for many, many sports. It has been a difficult time. So, we need to get athletes over there, we need to give them the best support they can possibly have to help them have their best day on the right day. If enough athletes do that, Australians will win medals and we’ll be rightly proud of them.”

Lovely. Wonderful. Certificates of participation for everyone. Let’s not even bother with keeping score. It matches the mantra of IOC founder Pierre de Coubertin: “The important thing in life is not the triumph but the struggle, the essential thing is not to have conquered but to have fought well.”

But we still want gold. Real life is the struggle these days. Sport is where we want to triumph. Rip into the Americans wherever possible. Give it to the Poms in an Ashes year. Beat Great Britain on the medal table for the first time since 2004.

We’ve had consecutive flat Olympic campaigns, with only eight gold medals each from London and Rio compared to the 16 and 17 at Sydney and Athens. Now? I reckon there’s 25 gold medal chances in Tokyo.

We’re not going to win 25 gold. Perhaps a dozen of them will get up. Perhaps more, perhaps less. Predictions are problematic – there’s been so few international competitions in the past year that no-one really knows where they stand. Most forecasts nominate Australia as having between 12 and 14 golds. But I think the following 25 athletes and events off genuine possibilities for the top step of the podium.

Ash Barty at the tennis, in singles and something she’s even better at, doubles. Elijah Winnington in the 400m freestyle. Ariarne Titmus in the 200m freestyle, 400m freestyle, 800m freestyle and 4x200m freestyle relay. Kaylee McKeown in the 100m backstroke. Two to Fox in her canoe slalom disciplines. The Matildas at the football and the Boomers at the basketball – two upsets, but not beyond the realm. Rohan Dennis in the road cycling. The Kookaburras in the men’s hockey. The rowing men’s and women’s fours. The men’s 470 sailing duo. Matt Wearn in the men’s laser sailing. Steph Gilmore in the women’s surfing. The women’s 4x100m freestyle and mixed 4x100m medley relay teams. The mixed team relay at the triathlon. Stewart McSweyn in the 1500m, just maybe. Nicola McDermott and Brandon Starc in the high jump, just maybe.

The best Olympic moments are always the gold-medal moments. The roaring instant of triumph. The fist-pumps. The high fives with teammates and coaches and opponents. The prohibition promoted by the stick men will be ignored. No one will be left hanging because in that mind-blowing moment of an athlete’s lifelong hopes and dreams being realised, it’ll be high-fives all round.

Stick men are more obedient and less emotional than humans. Give it another week. The sign of the times won’t be worth the paper it’s printed on.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout