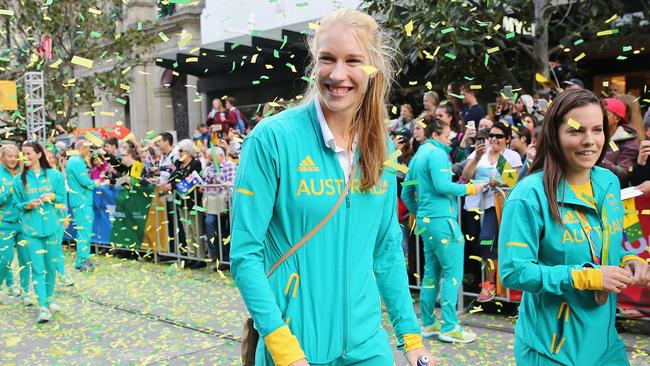

Kim Brennan urges rethink on career transition to avoid tragedies

Kim Brennan says sports need to rethink their approach to career transition in a bid to stop triumph becoming tragedy.

Olympic gold medallist Kim Brennan says sporting bodies need to rethink their approach to athlete career transition in a bid to stop stories of triumph turning to tragedy.

And in a week that saw swimming great Grant Hackett slip very publicly to the lowest of lows and the tragic suicide of 63-Test veteran Wallaby Dan Vickerman, Brennan said it was the sports themselves that needed to lead the cultural change.

“It is a risk factor when you go from a highly supported environment in a lot of ways. Sometimes that mental health support is not there and people assume that it is,” Brennan told The Australian.

“We have a lot of people who are falling through the gap and we need to ask ourselves why.

“A lot of those issues are perhaps exacerbated by the sporting environment, and there might be some issues unique to sport which brings a duty of care upon sporting organisations and sporting participants to really take ownership of it.”

Step one for Brennan begins on day one.

“We need to do a better job of having the conversation about life after sport right at the beginning,” she said.

“This isn’t a conversation you start having when you’re forced, or choose, to retire — it’s something you’re thinking about right through your time in sport.”

Brennan, who had been due to share the stage in Sydney with Vickerman tomorrow at the Crossing The Line seminar series aimed at athlete wellbeing and retirement, said having that continual conversation would create a sporting culture focusing not just on the athlete but “developing the whole person”.

“It needs to be a mindset shift and it needs to be the sport which drives it,” Brennan said.

“Our sports are great at developing sports people; we can do a better job at developing people.

“Sports are really focused on performance, but the reality is, if you have well adjusted happy people, they’re also going to perform better.

“In the past people would know, ‘Ah gee, that person’s got depression, there’s something wrong’, and sweep it under the rug. We’ll get them ready for the race and we’ll see what happened and it’s not our problem.’ But we need to be actually taking ownership — we need to care about these people in their entirety.

“You need to have an identity that isn’t entirely defined by what you do and we need to a better job in creating structures in the pathways out of sport.”

Brennan said the required wind of change needed to be aimed at some key pillars of high-performance strategy.

“Something that’s cited in sport is that psychology is often performance-related,” she said.

“People may have a fear of speaking about underlying mental health issues to a performance psychologist in the fear it will impact their selection or it will impact how their teammates see them.”

But Brennan, whose senior role on the Australian Olympics Committee’s Athletes’ Commission is to advise the AOC executive on athlete concerns, also believes athletes should play a role.

“It’s not only the responsibility of the people who are struggling to talk — it’s the responsibility of everyone to talk and to share and to learn,” she said.

“Sports are run on very tight budgets, particularly our Olympic sports, but some of those things are as simple as our beliefs and in a lot of ways this can be an athlete-owned thing.

“In our teams, in the culture of our sport, if the retired athletes can take a mentoring role with the younger athletes and say, ‘Hey, where do you see yourself in 10 years’ time? What can you do now to set yourself up down the track?’

“Everyone — coaches, administrators, athletes — need to take ownership and be aware of mental health.”

Before the London Olympics coaches and support staff did a mental health training course.

And Brennan said the Athletes’ Commission would continue to drive recognition by the AOC, which, she said, for the first time had committed money to explore the issue.