Athletics trapped in a moral maze over doping

The world championships in London demonstrated just what a moral maze the sport has found itself in over doping.

These are dangerous times for the sport of athletics. At the weekend, the world championships in London demonstrated the moral maze the sport has found itself in over doping.

Three big finals presented ethical dilemmas for followers of athletics. There was a Magic Monday at the Sydney Olympics and a Super Saturday at the London Olympics, but this was more like Suspect Saturday.

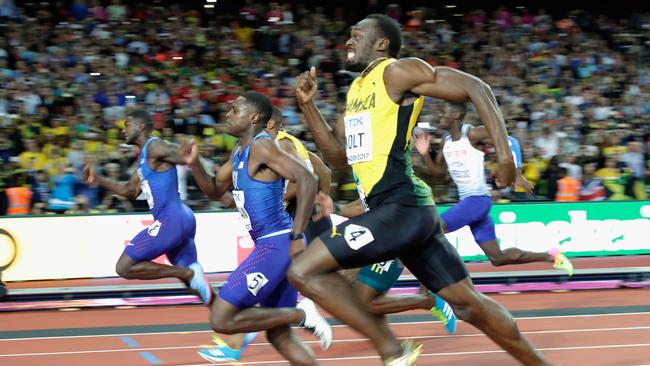

In the most-anticipated event of the championships, the man cast as the villain, the American sprinter Justin Gatlin, triumphed in the 100m, spoiling the farewell appearance of the man who has been the sport’s hero and saviour for almost a decade, Usain Bolt.

The women’s 10,000m featured an astonishingly dominant performance by Ethiopia’s Olympic champion and world record-holder Almaz Ayana, who has not raced all year due to injury but emerged to destroy the best female distance runners in the world, to the tune of 46 seconds, or most of a lap.

The immediate response from Scottish former world champion Liz McColgan was disbelief.

“So from 3k to 8k Ayana’s 5k split 14:30. Until Ethiopia follow proper doping procedures I for one do not accept these athletes’ performances,’’ she tweeted.

For a feel-good story of the night we had to turn to the long jump, but even there the spectre of drugs loomed.

South Africa’s Luvo Manyonga showed the power of sport to turn a life around, winning the gold medal four years after he spiralled into a meth addiction in his township outside Cape Town.

Manyonga tested positive for the drug in competition in 2012 and served an 18-month suspension, reduced from two years because the court accepted that he was an addict rather than a deliberate cheat. You can see the moral minefield here. Manyonga’s return and eventual triumph is widely regarded as a story of redemption, but Gatlin’s is not, at least not outside his homeland, where the media have been more forgiving of his past sins.

Gatlin has served two doping suspensions and was booed from the track by the largely British crowd after he took the title they had come to see Bolt win. Bolt said later he felt that reaction was “a bit harsh”, arguing that Gatlin had served his time and deserved his place on the track. But a few days earlier he warned “the sport will die’’ if athletes continue to cheat with drugs.

That’s at the heart of why the sport cannot get over this. The stakes are too high, it is fighting for its soul.

If athletes can serve suspensions and come back into the sport with a clean slate then the deterrence of being exposed as a drug cheat is diminished. It has to be the most shameful thing that athletes can do, because it is stealing from clean athletes, stealing their honours, their recognition, their money and in the context of sport that has to be unforgivable, or its integrity is lost.

In his post-event press conference Gatlin spoke eloquently of his efforts to put the past behind him and how he dealt with the negative crowd reaction to what was one of the most unpopular victories in the history of sport.

“I didn’t focus on the boos,’’ he said. “Through all my rounds I just zoned in on my lane. It was kind of sad that my boos were louder than other peoples’ cheers but I wanted to keep it classy. At the end of the race I bent my knee for Usain and paid homage to him and that’s what it is. It’s still a magical night for track and field and Usain Bolt. He’s done so much for the (sport) and I’m just happy to be one of his biggest competitors.’’

He pointed out that the jeering of him by crowds is a recent phenomenon. It has only happened as he threatened to beat Bolt in the past few years, and he pleaded that his behaviour had been exemplary since he returned from a four-year doping ban for testosterone in 2010.

“I’ve done my time, like he said, and I’ve come back,’’ he said. “I did community service, I’ve talked to kids, I’ve actually inspired kids to walk the right path and that’s all I can do.’’

He bristled when he was described as the bad boy of the sport.

“What do I do that makes me the bad boy? Do I talk bad about anybody? Do I give bad gestures? I don’t. I shake every athlete’s hand, I congratulate them, I tell them good luck. That doesn’t sound like a bad boy to me. It just seems the media wants to sensationalise it and make me the bad boy because Usain is a hero, and that’s fine.

“I know you have a black hat and a white hat, but come on man. You guys know I keep it classy.”

It should be noted that Gatlin is now 35, five years older than Bolt, who has run successively slower in each championship year since the 2012 Olympics, when he was 25.

Age got the world’s greatest sprinter in the end, not Gatlin, not the 21-year-old silver medallist Christian Coleman. But Gatlin is five years older, yet running faster and with his history, he will always be seen as suspect.

So even if he can be forgiven for his past mistakes, he can never be held up as a hero, and sport needs heroes to survive. It needs athletes that the public can believe in. Rightly or wrongly, people have believed in Bolt. In a decade when the sport has been beset by a series of drug scandals, Bolt has provided the antidote, but now he is departing the stage and we can truly see the frayed credibility of the sport.

So who can people believe in now, because while a certain amount of moral ambivalence is acceptable in normal life, it is intolerable in sport. Give it a try and see.

They may have won. It may have been a penalty. It may have been a world record. Sport only works in an environment of certainty. It requires belief to have any popular appeal. And that is in short supply in London right now.