To try to explain – or rather to speculate – about the factors that made him one of the game’s greats is cliche-fraught. To say a player “always gave 110 per cent” or “had a heart the size of Phar Lap’s” or “lived and breathed rugby league” does little to convey what galvanised him. What is inferred through imagery is far more effective.

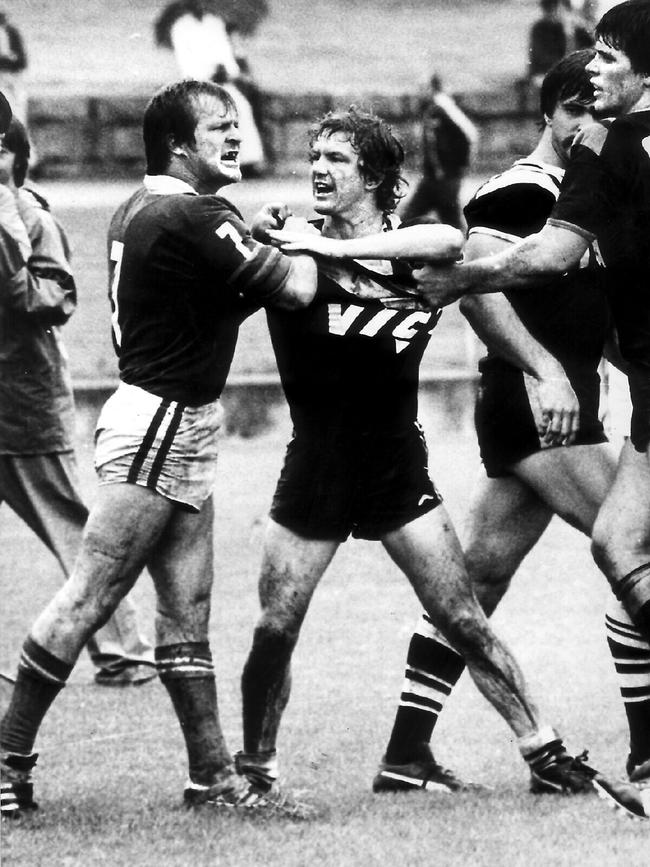

As a spectator at the infamous Manly/Newtown semi-final of 1981 at the Sydney Cricket Ground, I had my own insight into the Raudonikis persona, but it did not arise from the brutal and sickening brawl that occurred during that match. Rather, it was beforehand, seeing the man through binoculars as he prepared to tackle an opposition forward head on. I was taken aback by the look on Raudonikis’s face. It was not just a snarl, it was animal ferocity.

One unnamed sports journalist wrote in 1979 that Raudonikis’s ability to hate was such you could taste it. That was true, but it would be simplistic to say hatred was the primary attribute in his success as a player. That is not to gloss over his behaviour on-field, which at times was thuggish, something for which he was unrepentant.

Players of today are more likely to think of their opponents as adversaries, not enemies. For Raudonikis and his ilk, they thought the opposite. It was not enough to win, as that famous saying attributed to many a famous figure goes, others must be made to lose. No doubt Raudonikis’s philosophy was similar, and to resile from it reflected poorly on one’s self-worth. It was tribalism, but not the poisonous identity politics of today. Commitment to the club and its supporters was everything.

How the 168cm halfback came to dominate was inspirational, and a quote from former Newtown front rower Craig Ellis in 1980 is revealing in this respect. “I felt like giving it away,” he said, reflecting on his petering stamina in a cliffhanger against Parramatta. “But then I looked around and saw Tommy, with blood running down his face, racing around as if the match had just started. How could you let him down?”

It was not just a love of the game which attracted first grade players, it was their devotion to it. The money was just a bonus, and in most cases, not enough to live on. When Wests negotiated a six-year contract with Raudonikis in 1972 worth an annual $10,000, it was hailed as incredibly lucrative. To put that in perspective, the national average wage then was $7,133. The deal was good by comparison, but not enough to set him up for life.

Players were revered by the fans, but they retained their humility. Nearly all had full-time jobs – bricklayers, labourers, teachers, police officers and plumbers. Publican and Parramatta great Mick Cronin used to drive daily from Gerringong to Sydney to train. For them, these commitments were not extraordinary. But imagine having to front up Monday at a building site for a full day’s work after being battered on the field the day before – and to top it off, ending the day with sprint sessions. No wonder it attracted hard men.

By the mid-1990s, the money was such that many players could afford to make league their full-time job. And fair enough, for at best most have only several years to earn top dollar, and it qualifies them for very few high-paying roles post-league. But the professionalisation of the game has also meant losing touch with the communities it represents.

No longer are players the faces of what was once called the working class. That was inevitable, but gone too is the humility that endeared footballers to supporters. Even before the turn of the century, club officials were muttering that the work ethic had given way to indolence and entitlement, the young and well-paid players reluctantly interrupting hours-long Nintendo sessions to attend training. An idle mind is the devil’s playground, as many subsequent scandals have proved.

Raudonikis’s era was an age of forthrightness and fearlessness, and not just for the players. Former dual international Rex ‘The Moose’ Mossop was as outspoken a television commentator as he was player. While calling one match, he was distracted by a passing spectator who made derogatory comments about a member of Mossop’s family. “Excuse me,” said Mossop to his audience as he put down the microphone to confront the man and smack him in the mouth. For good measure, he did the same at halftime. Today the network would have sacked him, but back then it was summary justice.

In that era players spoke with a gruff sincerity. Now their every public – and sometimes private – utterance is scrutinised, leading in turn to carefully rehearsed platitudes. Conversely, Raudonikis was beyond colourful: he was irreverent. When speaking in 2011 at the funeral of indigenous footballer Arthur Beetson – another of the game’s greatest – he shared an anecdote that delighted the mourners. During a bush trip, said Raudonikis, Beetson’s sense of direction went astray, and he ended up 50km from his planned destination.

“Instead of going west like he said, he went south,” he added. “Talk about a black tracker, fair dinkum.”

Beetson and Raudonikis captained Queensland and New South Wales respectively in 1980, the first interstate match played under the current rules that give primacy to a player’s birthplace and/or state in which he first played. “Gee, the Queenslanders seem to be taking this seriously,” said Mossop after seeing Beetson belt Cronin, his Parramatta teammate.

The rivalry between the Blues and Maroons was legendary. It made for some of the best matches ever, although occasionally it went too far. Again as a spectator at the SCG when Australia played Great Britain in 1984, I and my mates enthusiastically joined the crowd in booing when Australian captain and Blues nemesis Wally Lewis’s image appeared on screen. Years later I read he was devasted his countrymen marred what should have been his proudest moment. I regret what we did.

As Test captain, Raudonikis was so overcome with emotion and pride he used to cry when the national anthem was played at international matches. I wonder what he thought of the ARLC’s decision to scrap the anthem at last year’s State of Origin opener, something reversed only through the intervention of Prime Minister Scott Morrison.

Remember when the ultimate honour in rugby league was being named in the Kangaroo Tour? When the game became commercialised, players regarded selection as an imposition. As I wrote last year, it said everything when those selected for the 2001 tour cited the 9/11 terrorist attacks as the reason for cancelling the trip, only to change their mind when someone pointed out it had not stopped The Wiggles from touring.

For me, Raudonikis’s death symbolised that the game as we knew it, and many of those who made it what it was, has now gone. Traditionally a chaotic and volatile sport, it has become predictable and ironically almost risk averse. Once a good hooker and his fellow forwards could command possession. Now it largely depends on the ability of a grubber kicker. And regarding scrums, I have one question. What is the point?

As for chaotic and volatile, I am reminded of Raudonikis’s interview with The Sydney Morning Herald’s Nick Yardley at the former’s house in 1981. Suddenly excusing himself, Raudonikis disappeared, only to re-emerge with an air rifle. His reason? He had just spotted a cat in his garden.

“They’re a bloody menace,” he said. “I wring their necks when I catch them.” But enough of Tommy’s good traits.

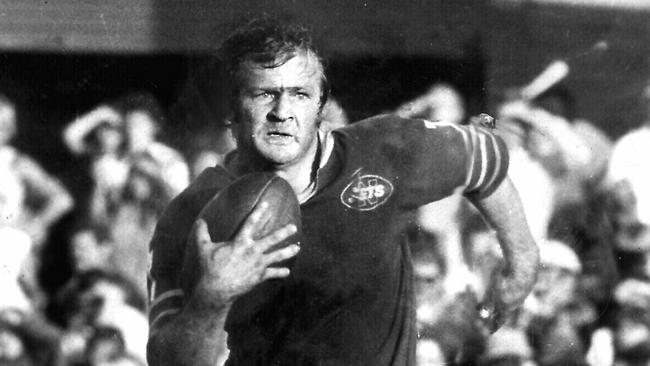

There were many rugby league contemporaries who, athletically, were superior to Wests and Newtown legend Tom Raudonikis, who died last week, aged 70. He was a realist in that he knew his limitations, but he never dwelled on them. “I have certain attributes and I have to make the most of them,” he said in 1980. He certainly did.