Indigenous Sport month: Cathy Freeman painting a picture of Indigenous identity’s pain and glory

Central to our national and sporting myth is the Indigenous athlete made good. They comfort us that reconciliation is at hand. Cathy Freeman is the most potent of them all.

In 1994, in the months before she won gold at the Commonwealth Games – and before she was castigated for daring to display the Indigenous flag upon winning those medals

The emerging athlete was doing a final photographic shoot before she left for events on the other side of the world

Small, quiet, shy until she felt comfortable with you, Freeman had a place in mind but did not tell Ludbey where they were going.

The car made its way towards High St, Northcote, where she found the place she wanted opposite the town hall.

“We pulled up and I saw this big mural and I thought ‘oh shit’,” Ludbey recalls.

“I looked at her and said ‘are you sure you want to do this photo?’ and she said ‘yep!’.”

The Northcote Koori Mural, by artist Megan Evans in collaboration with members of the local Aborigines Advancement League, is imposing. Figures depicted in it stand at least 5m high. A core element is based on a confronting photograph by German anthropologist Hermann Klaatsch taken in 1906 in Wyndham, Western Australia, of male Aboriginal elders in neck chains.

Ludbey took the shots quickly. Freeman is a small figure; the images of men in neck chains towered over her as she jogged along the footpath. The striking political statement ran on the front page of the Herald Sun on June 24, 1994, beneath the words “An athlete’s fighting spirit takes flight”.

Two months later she won gold in the 400m and 200m finals at the games in Victoria, Canada. She had anticipated the moment and had a friend waiting with a Koori flag on both occasions. Freeman also grabbed an Australian flag and did a lap of an honour.

Chef de mission Arthur Tunstall castigated Freeman after the 400m gold-medal flag celebration but she was not deterred from repeating the act when she won the 200m. Tunstall’s attitude was not wholeheartedly endorsed and half the Herald Sun’s readers polled on the subject backed her.

Freeman has mostly kept her silence on the moment, but spoke about it in a recent film, FREEMAN, saying she wanted to make a statement in the moments after she won those first gold medals. “I wanted to shout, ‘Look at me. Look at … my skin, I am black and I am the best there is, no more shame’,” Freeman said. “I have always been very mindful of my ancestors.”

Academics Gary Osmond and Matthew Klugman wrote a paper on the photograph and Freeman’s activism for the Journal of Australian Studies in 2019. “Politically she was neither innocent, vague nor naive, but acutely aware of gender, race, Aboriginality and her position as a role model for Indigenous Australians,” they wrote. “Freeman frequently told journalists that she was aware of racism through direct experience, including acts of violence and assault.”

Freeman’s lap of honour with the Australian and Indigenous flags after her 400m victory at the 2000 Olympics is celebrated as a moment of national reconciliation. It is not clear, however, that an Indigenous athlete would be permitted to do the same in 2021.

The IOC recently issued Rule 50, a ban against political protests at the Tokyo Games, apparently in response to the Black Lives Matter protests that swept world sport in the past 12 months.

A survey conducted by the Australian Olympic Committee Athletes Committee ahead of the Tokyo Games found that 80 per cent believed field of play and podium should be free from political protests. The great concern ahead of the Olympics is athletes taking a knee in sympathy with the Black Lives Matter movement. The knee is the new fist.

In 1968 gold medallists Tommie Smith and John Carlos were expelled from the American team and condemned by the IOC for raising a fist in sympathy with civil right movements of that time.

NSW Olympics minister Michael Knight sought special permission for the Indigenous flag to fly outside venues in 2000 and AOC president John Coates recalls Freeman asking him if she could wear the flag on her shoes although she didn’t need to.

He was not aware she would take the flag onto the track after the 400m final but had no issue with her doing so.

The AOC is waiting to learn more details of the latest edict from the IOC, however a spokesman said it viewed the Aboriginal flag as “a celebration of Indigenous identity”.

Mr Coates cannot imagine there would be any problem with Indigenous athletes celebrating with the flag. The AOC expects to have about 10 Indigenous athletes on the team of 480 at the games.

“I don’t see any of our team members using an Aboriginal flag as a demonstration,” Mr Coates said. “It is something they are proud of but the IOC is still working out its guidelines what will be a protest or a demonstration.”

Indigenous heritage

Central to our national and sporting myth, nourished by Freeman at Sydney 2000, is the Indigenous athlete made good. The exemplar to their people of what is possible and a signal to the broader community that race is no great matter. They comfort us that reconciliation is at hand.

Freeman is the most potent of them all. On the world stage the former Australian of the Year lit the Olympic flame and framed the Australian moment with her gold-medal run.

Previous decades had offered similar narratives.

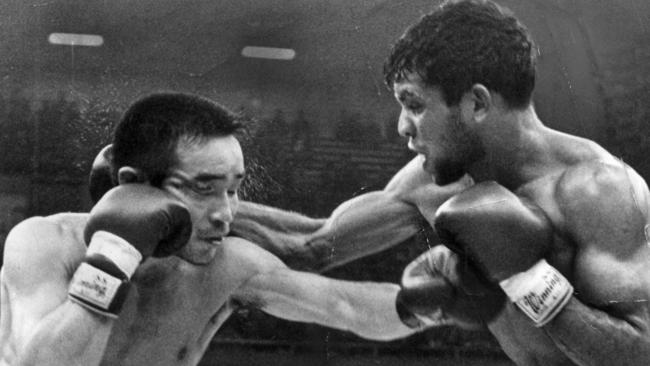

Lionel Rose was one of nine kids born in a shanty house at Jacksons Track. He lost his father at 14 and found his way out of poverty through boxing – one of the few sports that offered a path to Indigenous athletes.

At 19 the fresh-faced star defended his title against Rocky Gatellari then travelled to Japan where he defeated highly rated champ Fighting (Masahiko) Harada over 15 rounds to claim the world title.

Rose was a national hero and was given an open-topped car ride to a civic reception in Melbourne on return. Reports claim a crowd of up to 250,000 (some say 100,000) lined the streets to greet the young man on his return.

Mike Willessee, host of the television show This is Your Life, claimed the Beatles and visiting US presidents had failed to attract that much attention.

Rose was so popular he had a chart hit with a song written by Johnny Young and he fashioned something of a side career for himself as a performer.

The 1970s were a feel-good time for Australia and its Aboriginal sportspeople. Evonne Goolagong (now Cawley) shared the national spotlight when she won seven singles titles, including two at Wimbledon. The tennis player featured in an advertisement for Kentucky Fried Chicken – complete with tall glasses of milk – at the height of her popularity.

Football celebration

This weekend both football codes celebrate Indigenous round with show reels of greats past and present.The AFL nominated Syd Jackson, the godfather of Indigenous small forwards, as its Sir Douglas Nicholls honoree. The league put together a highlights package of the brilliant Carlton rover who was born on a mission. He believes we’ve come a long way, but still have a bit to go. Nicholls started his VFL career at Carlton, but was denied physiotherapy because he was black and told he smelled.

Fox Sports has cut together a brilliant package of NRL stars past and present to a soundtrack from Indigenous rapper Baker Boy. The league’s fixture lists offers the Indigenous place names of the venues as well as their more common handles.

The AFL’s Indigenous round is stained by events in recent times. Amid all the pride in the jumpers, the flag and the culture is a lingering shame related directly to events that occurred in the 2013 Indigenous round.

Role models

Eddie Betts, the celebrated goal sneak acknowledged the sorrow in an interview with the Seven Network aired over the weekend.

Asked to nominate a mentor, the footballer who played against Sydney at the SCG on Sunday, nominated Adam Goodes.

“I looked up to Adam, a two-time Brownlow medallist, a premiership player, a best and fairest, he’s won every medal and just the way he finished his career was pretty sad to see,” Betts said.

“He gave me a voice to speak up and I kind of feel bad that I didn’t help Adam enough in the period when he was struggling.”

Goodes was infamously driven from the sport he loved and excelled at by abuse as bruising as any baseball bat.

Steve Georgakis, a senior lecturer of pedagogy and sports studies at the University of Sydney believes the treatment of Goodes was a clear message to other Indigenous sports people.

“He becomes like a scarecrow for other Indigenous people: if you go out and you cross the line you will do it at the expense of your career,” Mr Georgakis said.

“Aboriginal athletes are going to be hesitant to speak out about issues. I can’t understand that, as a society, if most of us are saying sport is an area that has privileged Indigenous people, most of our Indigenous success stories have been in the domain of sport, but even if that’s the case there is still we don’t allow Indigenous athletes to be active on political issues. The Adam Goodes thing is a perfect example. At the end of his career he made a decision to address issues and as soon as he did, for the most part, the football community and wider community were against him.

“That’s the first discourse, sport’s been this institution which has addressed the gap but when it comes to athletes themselves being activists we don’t like it. We say look at what we gave Adam Goodes, we made him Australian of the Year and how does he repay us? Well he repays us by saying ‘you know what there is discrimination in our society’.”

Former Swans and Collingwood player turned ABC journalist Tony Armstrong was playing for Sydney the year Goodes was abused at a Collingwood match and says it highlights how far Australia thinks it has come compared with how far it has actually come in acceptance of Indigenous athletes.

“If anyone had ever earned the right to talk about something honestly to his country it was Adam Goodes,” Armstrong said. “Take away his skin colour, take away his cultural heritage, this is a man who got to the top of his sport through hard work, diligence, skill, toughness and reliability. These are all classic Australian traits.

“He was giving back through his Go Foundation with Michael O’Loughlin, he was made Australian of the Year. This was a man held in high regards … Then we gas lit him as a country … It was a huge message to Indigenous athletes but to Indigenous people in general.”

International incident

The vilification of Goodes gained international attention. It was the subject of two documentaries and is a chapter in a new book by cricketer Michael Holding that will be released next month.

The West Indian cricketer’s off-the-cuff comments on the Black Lives Matter movement during a Sky cricket broadcast sparked such a reaction that he has written a book, Why We Kneel, How We Rise. It includes a number of interviews including one with Goodes in penultimate chapter.

Goodes’ politics sat uncomfortably with right-wing commentators. His Australia Day speech was selectively quoted to make it appear divisive and his actions in pointing out a 13-year-old who racially abused him during the Indigenous round game in 2013 have been used against him by jeer leaders in the media.

Eventually he had to walk away from the game.

Goodes’ critics blamed the footballer for attacking a child, but he had been clear from the morning after the event she was not to blame.

“I just hope that people give the 13-year-old girl the same sort of support because she needs it, her family needs it, and the people around them need it,” he said at the time. “It’s not a witch-hunt, I don’t want people to go after this young girl. It’s not her fault. She’s 13, she’s still so innocent, I don’t put any blame on her.”

When Goodes did an Indigenous dance in celebration after kicking a goal at the SCG in 2015 he was criticised for frightening fragile white people with his imaginary spear.

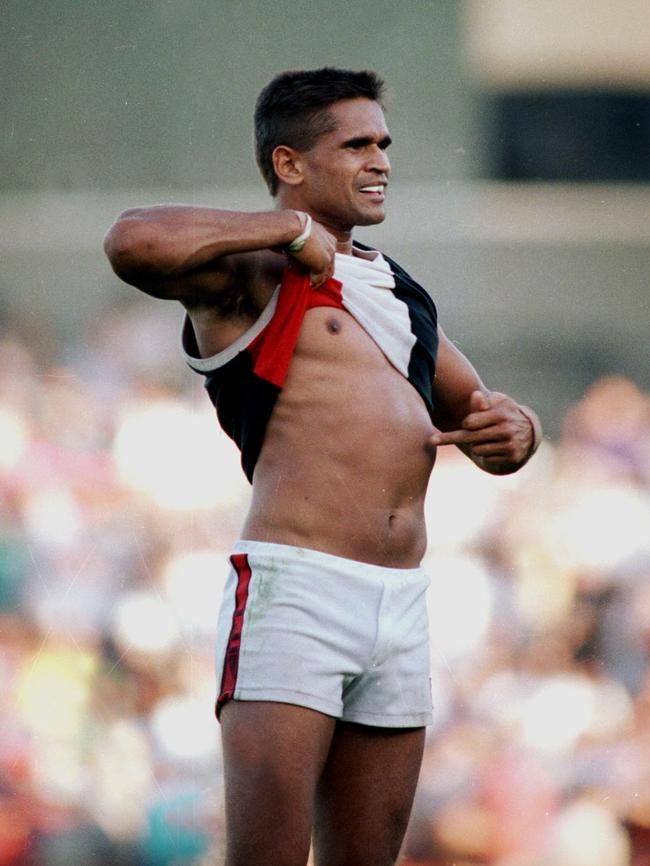

Gary Osmond of the University of Queensland has written extensively on Indigenous activism and sees a link between Goodes and the abuse of Nicky Winmar.

The image of Winmar pointing to his skin in response to racial abuse during a match against Collingwood in 1993 is seared into the Australian sporting conscience.

“When Adam Goodes pointed to the teenage girl in the crowd it is almost the reverse of the Nicky Winmar incident in the 1990s when he is pointing to himself,” Dr Osmond said. “He is saying I’m black, he’s not pointing at white people, whereas Goodes is pointing directly at the spectators saying this is your problem, it isn’t my problem any more.

“The inversion of the finger says something about the fragility of white Australians.

“The crowd and the media would have been incensed if Winmar starting pointing at the crowd. What he did was very dignified and appropriate for the times, it’s an image that carries weight because of that quiet dignity and pride.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout