If you love football, you love Maradona

Forget the cheating, Hand of God and slide into drug use, Diego Maradona is on the dais as the greatest of all time.

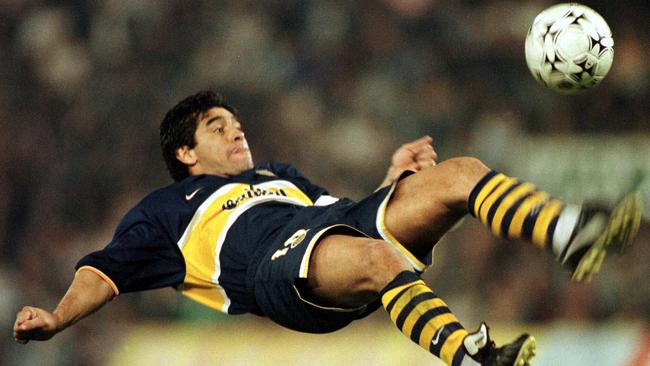

Diego Maradona was the greatest player I have ever had the privilege to report on, attempting somehow to find the words to capture the magic that this small, stocky Argentinian could conjure up even when opponents were attempting to slice him into tiny pieces.

So ignore the cheap retrospectives of his career that focus on the bouts of cheating, the Hand of God against England, the sad slide into drug-taking brought on by the pressures of fame and brutal attentions of unscrupulous defenders. Because it’s really very simple: if you love football, you love Maradona.

You love his poise under pressure. You love his technique, his vision, his incredible invention. Everyone has a special moment of cherishing the perfect 10, whether experienced in the flesh or viewed from the sofa, open-mouthed in admiration.

Those of us fortunate enough to be in the sweltering Stadio delle Alpi on June 24, 1990, for Argentina v Brazil in the World Cup round of 16, marvelled at Maradona weaving past Alemao, Dunga and Ricardo Rocha, instinctively knowing that Claudio Caniggia was off and running.

Maradona instantly found his accomplice with a pass that really required a compass to locate its intended target, even though he was off-balance, even though the ball needed playing with his supposedly weaker right foot. Even though the timing was so tight, the second so split it was close to being fractured into minuscule shards, Maradona delivered.

Only he could. Only he could pick out Caniggia, who promptly skipped around Claudio Taffarel and scored. Those lucky enough to be in Turin knew they were in the presence of genius.

Heading from the ground to the tram stop afterwards, I picked up a discarded Italia ‘90 flag, which hangs in my study along with pictures of Maradona (and others, I’m not obsessed). Much of the talk of that tournament was of how Maradona dealt with the callous dispensers of pain that ambushed him, the Cameroonians in the group stage who battered him. Victor N’Dip caught Maradona so high that the skin below his left shoulder showed a stud mark afterwards.

He got on with the game.

He punished opponents with his skill, occasionally with acts of calumny, like the Hand of God against England in Mexico 1986. Yet England manager Bobby Robson’s players broke off from their own warm-up to marvel at Maradona juggling the ball. If you love football, you love the skill of Maradona. The Hand of God was a true footballing deity.

You’d pay to watch Maradona warm up, even to see him when the referee tosses the coin up, when the great Argentinian would simply conduct the formalities while toying with the ball on the centre circle, sometimes doing his signature trick of stamping down one side and letting the ball float upwards like an admirer craving his close company. Gravity joined in the fun, guiding the ball down on to that left foot, less body part and more work of art.

The ball would fly up again, swooning, flicked high into the air, and then descend on to Maradona’s left shoulder. One, two, three, four times he would lift it back up. Maradona could control a ball better with his shoulder than some players could with their feet. This is why Maradona should be celebrated. The skill.

Maradona possessed such gifts that Robson spoke to his players in Mexico about man-marking Argentina’s most potent threat but decided against it. How do you trap mercury?

Belgium tried in the semi-final, putting Eric Gerets on Maradona, and failed. Peter Reid once told me about his recurring dreams about Maradona in the Azteca, and trying to get close to him.

He didn’t in reality, did he in his reverie? “No,” Reid said, laughing. “Maradona turned me and Peter Beardsley on the halfway line.” And disappeared. He ripped apart a good England defence, including Terry Butcher and Gary Stevens. He beat an outstanding England keeper, Peter Shilton. “You have to say that is magnificent,” purred Barry Davies.

The sumptuous skill remained. During his time as Argentina coach, Maradona held an open training session at the Springboks retreat in South Africa at the 2010 World Cup. I went along, and was bemused at the shooting drill that Maradona organised. He pinged in low crosses, mis-hitting each one towards Lionel Messi, Gonzalo Higuain, Sergio Aguero and Carlos Tevez.

“Has his touch gone?!” I asked an Argentine reporter friend. He laughed and explained. “Diego knows they can score from ‘clean’ balls in, so he gives them ‘dirty’ balls.” Even Maradona’s bad balls were good.

At the end of the session Maradona strolled back towards the pavilion for an utterly chaotic press conference with the world’s smitten media, standing room only. As Maradona walked across one of the Springbok pitches, he saw a discarded rugby ball. Maradona knew the Pumas game, and casually nailed the egg between the posts as he passed. Round ball, oval ball, any ball. He had the skill.

Only two players can be cherished in his bracket, can share his pedestal. Before Maradona was Pele, arguably the greatest of all time because of his three World Cups, yet fortunate to be surrounded by world-beaters, from Garrincha to Jairzinho.

After Maradona came Lionel Messi, the most mesmerising of the modern era, far more humble than his compatriot, but lucky to play alongside accomplished teammates with Barcelona and still failing to inspire Argentina as monumentally as Maradona did in 1986.

The miracle of Maradona was that even though he was pursued by the mafia and the media, by brutal man-markers who set out unashamedly to mark the man, the likes of the “Butcher of Bilbao”, Andoni Goikoetxea, that he kept playing, kept taking on defenders, kept being the boy from the slums of Buenos Aires who had to entertain, who had to win. Any how.

He lived a life. A year after the Azteca, he happily turned out for the Rest of the World all-stars against a Football League XI at Wembley and there were some boos, but patently of the good-humoured variety.

His warm-up, that Maradona special of leaning down to pretend to pick up the ball and kicking it forward, brought the house down. Later that night a partying Maradona almost brought the roof down at Tramps nightclub.

Three years ago Maradona was presented on the Wembley field at half-time of a Tottenham Hotspur game against Liverpool, and the reception was rapturous. English fans appreciate class, and are prepared to put past anger behind them to acknowledge greatness. If you love football, you love Maradona. Rest in peace.

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout