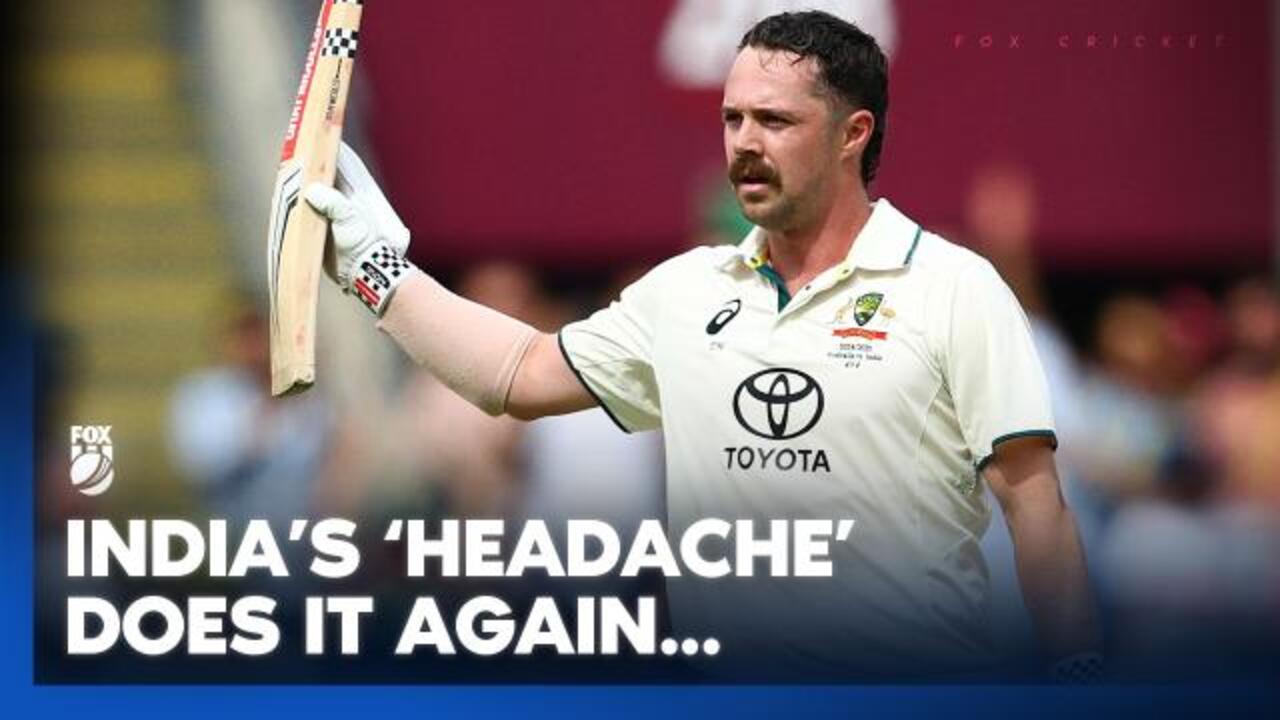

Travis Head is one of a kind and the figurehead of adventurous Test batting

Travis Head is an anomaly. There have been others who’ve liked taking the game on. But none do it like the Australian Test No.5.

Travis Head is not the norm. He’s an anomaly. He’s a one of a kind. He’s got no parallels.

Travis Head is also the figurehead of adventurous Test batting in the current era. With good reason. There have been others before him who’ve liked taking the game on. There are others around him who thrive on taking the game down. But none do it like the South Australian does. Not with the same consistency. Not with the same sense of inevitability.

Just for the record, Head has scored 33.2 per cent, nearly one third of all the runs Australia have totalled across the first three Tests of the Border Gavaskar Trophy. That is staggering, especially when you consider his style of batting is always associated with risk-taking.

But the thing with Head is he doesn’t really think he’s taking risks when he is playing shots that we’d think and describe as being audacious. He’s simply doing what comes naturally to him.

We gasp when he cuts a ball that is on an off-stump line through point. We wince when he airlifts a ball that’s full on middle-stump and deposits it behind deep backward square leg. But it’s not like Travis is taking undue risks in his head playing these shots.

There’s always a method to his perceived madness. Quite literally.

The reason he’s able to pull off his trademark cut shots off deliveries which we say aren’t there to be cut is because of the way he sets up. By crouching low on leg-stump without any back and across trigger movements the way he does, the left-hander is in the perfect position to use his bat like a rapier because of the natural room he creates. For Head, it’s as straightforward as a more conventional left-hander square-cutting a ball on a virtual fifth stump to the point boundary. It’s the same reason he’s able to whip deliveries which are on middle and off to regions on the on-side while most others aren’t. Travis isn’t trying to be a daredevil. He’s just trying to be Travis.

Also, take his 241-run partnership with Steve Smith on Day 2 at the Gabba. If anything, the oohs and aahs during the stand came when Smith was on strike. Not when Head was playing his game. It’s an ode to how he’s managed to find stability and solidity with his technique and approach to Test batting, despite all the unconventionality related with it.

The fact is that there aren’t genuinely too many batters in the same mould as Head. England’s Harry Brook comes the closest. Someone who’s not only blessed with extraordinary skill-level when it comes to curating their own batting textbook, but also then can be consistent at what they do, as their current Test averages suggest. Yashasvi Jaiswal is up there too, having broken the record for most Test sixes in a calendar year with 34, while also having scored a Test century at a strike-rate in the 50s in Perth.

No wonder both have managed to be successful across formats, with Head’s Test batting a reflection of the way he goes about his work in 50-over cricket, with multiple gears unlike the way he breaks games in a matter of a few overs in T20 cricket. You can’t really differentiate his famous knock in the World Cup final last November from what he’s dished out in Adelaide and at the Gabba these last two weeks.

In many ways, Head is both the torchbearer and the pioneer for what future Test batters will be like. We are if anything in a middle phase where we’re seeing a lot of transitioning between the more traditional types like Usman Khawaja, Marnus Labuschagne and Cheteshwar Pujara into a lot of ultra-aggressive and kamikaze batters.

Unlike Head, the likes of Ben Duckett and Rishabh Pant aren’t the type who will find a tangible method to their madness. For all the calculated risks they take with their ramps and reverse-ramps, there’ll always be a wild low-percentage swing at a fast bowler after they’ve jumped out of their crease.

But a batter like Head will become the norm for sure as we move towards the next decade of Test cricket. This is if anything a middling phase in the evolution towards Test cricket played on fast forward, but with a few layers thrown in between.

The rain-affected result in Brisbane was after all only the fourth draw in the last 61 Tests played across the world in this current cycle. While some records suggest that most Test matches average 3.2 days at the moment. There are a number of factors that have led to this phenomenon of course.

A generation of batters being in a hurry after being brought up on a heavy dose of white-ball cricket is only one significant reason for it. For, now there’s more emphasis on batters with the best hands and the best eye, rather than those with the best feet or footwork. Patience is no longer a necessity to succeed at Test level, it’s a virtue, often considered outdated by some. Or so it feels every time you hear Duckett revelling in his refusal to leave deliveries as a Test opener. And you know have batters the world over who simply cannot resist their need to feel bat on ball, leading to a handful of deliveries outside off-stump in an over being made to look like a masterstroke from the bowling group.

Whereas only a generation or two ago, a batter punching the ball on the up on a slightly difficult pitch was looked at as being impudent, batters these days will do the same but also then use their arm extension to try and hit it over the infield. Which in return leads to their technique and temperament getting found out on a pitch with any level of spice in it.

And the fact is that the pitches since the inception of the World Test Championship (WTC) have become spicier. Teams are now desperate for results on home soil, leading to the preparation of rather bowling-friendly surfaces, even if it means throwing their own batters into the deep end.

Even if it results in backfires, like India losing to New Zealand 3-0 on dustbowls in the lead-up to their tour of Australia. South Africa on the other hand are on the cusp of making the WTC final after having produced pitches custom-made to suit their battery of fast bowlers. And it worked earlier this year against a much-more fancied Indian outfit.

Of course the art of seeing off spells is mostly done away with or not celebrated as it used to be in more conventional times. So is the old adage of go slow when conditions are challenging. Test batters of the current era instead prefer to go faster or the fastest when the bowlers are having a ball. The spicier the pitch, the more aggressive they are. With the knowledge that a total of 200 in a potentially two-day affair is match-winning, as are quickfire 30s and 40s instead of drawn-out Test tons. As a result, bowling averages are dropping almost as rapidly as batting averages around the world.

The modern pace of Test cricket often throws up plenty of discussion about the possibility of turning the oldest format of our sport into four-day affairs. Probably the best way out might be to wait it out, for the Travis Head-inspired next gen of calculated risk-takers are not too far away. They should be able to keep five-day Tests will stay in vogue.

For if you do drop a day now, don’t be surprised if teams start going even harder, scoring even quicker and starting to finish matches in even more rapid fashion. What next then? Three-day Tests? You see where we’re headed.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout