The private battles of cricket star Moises Henriques

Star cricketer Moises Henriques was one of Australia’s best. But privately, he was facing his greatest test.

The gas bottle. The barbecue wouldn’t light. The gas bottle must have been empty. Now he’d have to do something about that. But he couldn’t, just couldn’t.

It was the afternoon of Christmas Eve last year, and Moises Henriques was in the backyard at home in Clovelly, Sydney, readying for an evening visit from friends and family. The 30-year-old — tall, strong, handsome, financially secure, widely respected — had been among Australia’s elite cricketers for nearly a decade. He had led his country in an under-19 World Cup. He had faced the world’s fastest bowlers, dismissed the world’s best batsmen, represented his country 26 times, appeared before the teeming stands of no fewer than five Indian Premier League franchises. He was captain of the NSW Blues; he had, just the day before, skippered the Sydney Sixers in a Big Bash League match watched by more than three-quarters of a million people.

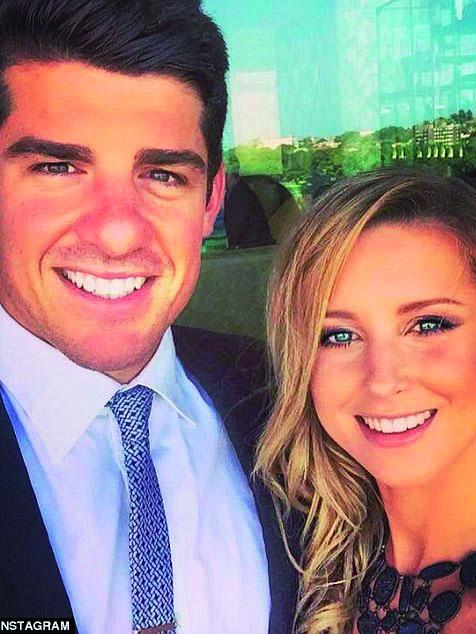

Now he was on his knees and had tears pouring down his face at the prospect of refilling a gas bottle. Coming into the backyard, his fiancee Krista rushed to his aid. What was wrong? The service station was close. The bottle was not a problem. And, of course, it wasn’t. But Moises could feel his chest constricted, his pulse racing, his thoughts cramming up against each other. He began pleading with Krista to cancel the gathering. The truth was that he’d been feeling like this for ages. He could not let people see him like this.

Krista calmed him, arguing that he would be better for the company. She’d do everything. He could relax. The cylinder was refilled. The night proceeded. Moises strove to keep it together, but there was no mistaking his subdued mood. Former England batsman Michael Lumb paused with Krista by the door as he was leaving with his wife. “Is Moey OK?” he asked quietly. “He seems… dark.” When Krista repeated the remark afterwards, Moises again felt his chest tighten. He knows, he thought. Everyone knows. But if only they knew how it felt.

Nine months after his gilded life as an alpha athlete crumbled last Christmas, Moises faces a new season more hopefully — but “how it felt”, and what lay behind a withdrawal from cricket explained as “for personal reasons”, he feels bound to share. That instant when the tiniest task seemed insuperable came at the end of years of depression suffered silently, and perhaps for decades endured unacknowledged.

In a cricket scene in which they do not abound, Moises Henriques is a leader. He was a precocious junior all-rounder — more advanced in his teens than either of his contemporaries and friends Steve Smith and David Warner. If he has not quite fulfilled the buoyant hopes for his talents as a top-order batsman and pace bowler, he has stood out for his pacific temperament and interpersonal skills. He first led NSW aged 22. “Some people like being captain but don’t like rolling up their sleeves, having tough conversations,” says his teammate Ed Cowan. “Moey has been doing that since he was a really young man.” Says the state’s assistant coach Geoff Lawson: “He’s a good man to the core.”

Like a good man, Moises soldiered on through Christmas, which was stressfully split into three visits: to Krista’s family and to each of his long-estranged parents. On Boxing Day, he trained with the Sixers at the SCG. When he returned home, he cried for three hours. By now, Krista was insistent: he had to see someone. She messaged the player welfare manager at Cricket NSW, Justine Whipper. Whipper had been at CNSW for five years, and become something of an institution — warm and empathetic, a trusted confidante of male and female players alike. She had worked closely with Moises, notably after the death of his friend and teammate Phillip Hughes, who was mortally wounded by a cricket ball in November 2014. “He was in deep grief, but so rational and so fair with everyone,” she says. At times, Moises had confided worries and sensitivities. But when she asked him to rate his distress on a scale of one to 10, Whipper was shocked by his answer of “seven” — adjusted for Moises’ stoicism, that was near the top of the range. Whipper went in search of a diagnostician for her men’s captain, but in the holiday season could find no appointment earlier than the morning of December 28 — hours before Moises was due to captain the Sixers in their next game. It would have to suffice.

Greg de Moore is associate professor of psychiatry at Westmead Hospital. He works from a dour facility on the site of the old Parramatta Hospital for the Insane — a museum there contains all the instruments popularly associated with the treatment of the mentally ill, from straitjackets to an electroshock machine. Arriving with Krista, Moises couldn’t help thinking of the movie One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. But he was determined to keep it together.

De Moore recognised Moises: a cricket lover, he had penned a fine life of the troubled colonial sporting prodigy Tom Wills. He also recognised Moises’ type — a high-functioning “coping individual” suddenly overwhelmed. De Moore has seen surgeons operating one day, completely prostrated the next; he has known barristers to proceed almost straight from court to collapse. They can be awkward patients. “In psychiatry, you only ever get a ‘version’ of the person,” he notes. “And the coping individual can reconstitute quickly: they want the psychiatrist to give them a ‘good report’. But as that interview [with Moises] went on, you saw all the little red flags.” The flat manner, the helpless cognitions, the poor sleep, the lost appetite: they spelt out major depression. “The people who picked this up had done an excellent job,” de Moore reflects. “But he was probably in a worse way than they realised.” He was struck by Moises’ carriage. He stood straight; his bearing was “almost military”. But he walked as though sore: “Moises was a man who limped both inside and outside.”

Such limping is ever more public and no respecter of reputations, here (Ian Thorpe, Greg Inglis, Barry Hall) or abroad (Serena Williams, Michael Phelps, Andrew Flintoff). An episode of Four Corners last year, After the Game, shone a light on the difficulties experienced by elite athletes in leaving their sporting identities behind, with an accent on the suicide of former Wallaby Dan Vickerman. But the mid-career “leave of absence” to deal with mental demons is increasingly common in the AFL: last year it was Western Bulldogs star Tom Boyd; this year Brisbane Lions captain Dayne Beams.

For its part, Cricket Australia has been researching the prevalence of mental maladies for about five years. Data collected recently by mental health consultancy Orygen suggests a “caseness” (a level of symptomatology warranting treatment by a health professional) of about a quarter of the elite playing population — roughly in line with the general population. We may exalt our cricketers, hold them to lofty standards, imagine them to be “living the dream”, but they are as susceptible to malignant sadness as anyone. And given that Moises is the first Australian cricketer to talk openly about his troubles, that suggests a good deal of silent suffering.

To young Moises, born on the Portuguese islandof Madeira but raised in Sydney’s industrial Peakhurst, sport was the world. His parents separated, acrimoniously, when he was 11. Moises remained with his father, Alvaro, while his younger brothers, Nicholas and Robert, lived with their mother Annabela. Alvaro worked punishing shifts at a sheet metal factory and was a taciturn parent, never violent but sometimes brooding and withdrawn. Moises would get himself off each morning to Endeavour Sports High School, where cricket reciprocated his love and he flowered into a hard-hitting, fast-bowling prodigy, first representing Australia at under-17 level. Picked for his state at 18, he became the youngest Blue to take five wickets in an innings since Doug Walters.

Then Moises was hit by injury. His young hamstrings and calves tore; his shoulder had to be reconstructed; the changed kinaesthetics affected his confidence; cricket did not “feel” the same. He finally broke into the Australian team in January 2013 and played three Tests in tough conditions in India, making 68 and 81 not out on debut. But he slipped back almost as quickly and on an Australia A tour in his mid-20s began experiencing almost existential doubts: “I remember looking around and thinking, ‘I don’t even know why we’re here. What are we doing this for? Everyone’s playing for themselves’… We hadn’t trained together. I didn’t know the person next to me. I started to notice the selfish traits in other people, got a bit obsessed with them. I just wanted to go back and play for NSW, because it was something I felt part of.”

Sometimes, when Moises parsed the comments he heard from coaches, cricket even seemed a bit ridiculous: “They would say: ‘You’ve always got more time than you think.’ Then they would say: ‘Take the game on.’ Well, which was it? Next it would be: ‘Try to get them doing something they’re not comfortable doing.’ Well, what are these ‘somethings’ exactly? ‘Have a clear mind.’ But you’re never going to have a clear mind: you’ll always be thinking something. ‘Go to your strengths.’ What does that even mean? We were just saying words.”

Moises kept a lid on these dissatisfactions. But about his cricket, much of the time he felt frustrated. He would get in a funk about his batting when he fell short of an imagined perfection. He would punish himself by the standards he set his bowling. The strange thing was that these behaviours were effectively endorsed: he was admired by his peers for his dedication and self-sufficiency. “I trained hard — probably too hard,” he recalls. “I wasn’t outwardly emotional. I kept a level head. I made sensible decisions in facets of my life, like buying a house. Then I’d go through stages where I’d think: ‘I’m struggling here. Can someone just help me?’ ” But he felt incapable of asking. In hindsight, Moises grasps that his desire for help and his resistance to seeking it involved more than cricket — they simply localised and concentrated in what was the chief source of his self-definition. At the time, there was a simpler recourse: hating the game.

Cricket did not simply lose its lustre for Moises; it became a torment. Short-form cricket at least was over quickly. Long-form cricket left him sick with sleepless dread: “I never slept during Sheffield Shield matches. I’d dwell on a day for four hours, then fear the next day for three.” Success alleviated these agonies only temporarily, and afforded respite rather than satisfaction. He would find himself thinking: “You used to love this game. You still love training, trying to master your craft. Why are you not enjoying what you used to thrive on?”

Beneath it all lay a substratum of thought he barely understood. Like most cricketers, for example, Moises was devastated by Hughes’s death. Yet, as Whipper noted, it brought forth his best, turning him outward from his preoccupations. “For the first 36 hours I was an absolute mess,” Moises recalls. “Then I thought: ‘Maybe I can help other people.’ I wasn’t getting satisfaction from doing what I had to do, but I’ve always felt valued when my friends have thought they could rely on me.”

Moises handled the calls from anxious friends and cricket contemporaries all over the world, took the soundings in the dressing room, deflected the pressure to rush back to competition: “You had the officials saying: ‘You’ve got to get out there again. It’s the best way to deal with things.’ And I was saying: ‘Hey, you don’t know what the best way to deal with this is. It might be for some people, but it won’t be for others. There’s no precedent here. Let individuals make their own decisions.’” Personally, Moises did not want to play the Shield round finally scheduled for 12 days after Hughes’s death, but as captain felt he owed it to those who did. He remembers vividly dismissing Usman Khawaja caught in the gully, punching the air in delight, then as he was walking back to his mark breaking into tears, so wrong did pleasure feel.

He was inclined to such tangled thinking anyway. In a T20 at Arundel in England in June 2015, he collided with a Surrey teammate going for a catch so violently that three surgeries were needed to reconstruct his broken jaw. His first thought on coming to was of Hughes: “I’m so lucky that wasn’t worse.” His second was relief: “I’d been anxious before every game over there, and we were just about to play 21 days of cricket in the next 24. I had been dreading the weeks to come. At least now, I thought, I didn’t have to play.”

By this time, Moises had sought help from various psychologists, who had treated his thoughts mainly as challenges of motivation — not uncommon among mid-career athletes, for whom the end is distantly looming. Yet the mechanism most helpful to him had always been counterintuitive: he would accept no contract longer than a year. For many athletes, insecurity is a bane. Moises welcomed it, arguing that he “played better under pressure”. In fact, he now says, he liked the reassuring sense that the exits were not sealed.

The night before the first Sheffield Shield game of 2016-17, he was panic- stricken: “It was the worst headspace I had ever been in. Not only did I not want to play, I wanted to give the game up completely.” He located a new psychologist, who recommended a number of tools, from meditation to a gratitude diary, including cognitive behaviour therapy to promote more positive thoughts. It correlated with the best season of his career: 775 first-class runs at 64.6, 414 one-day runs at 69, 615 T20 runs at 38.4.

Moises often still felt terrible, caught up in a cycle of lacerating thoughts. No sooner had he been dismissed in matches that he would start to fret over his bowling; when he finished bowling, he would commence brooding on his batting. “It was the four-day grind that spun me out,” he says. “You’re just looking for a place to hide, but the game comes back at you again and again.” Yet outwardly, he was at last the dominant player he had always threatened to be. It was an equilibrium he could just about live with.

In April 2017, he defied his old custom and signed a four-year contract with the Blues and the Sixers. There was rationale for certainty: Moises and Krista were planning to marry, to buy a matrimonial home and start a family. Not all at once, but over the course of winter with Sunrisers Hyderabad and Surrey, signer’s remorse set in. Caught up in the busyness of the day-to-day, Moises let his therapeutic regimen slip, while the psychologist who had helped him went on maternity leave. As the home season began, he felt stale, drained; he craved a break, but the solace of possible escape was gone.

Just when he needed them, too, the runs and wickets dried up. A couple of good deliveries, a couple of ordinary pitches, and suddenly he was “out of form”, and not just with the bat: “My head was in such a bad space. I really had no idea. I was second guessing everything… After four matches, I’d scored 100 runs in seven bats. I thought: ‘I’m nowhere here. F..k, I hope they drop me. But they won’t because I’m captain.’”

So Moises had to keep going. One day at training, Lawson caught a sidelong glimpse of him. He had often worried about Moises’ masochistic dedication to practice, and sometimes physically pried the ball from his hand. Now, he felt, the cricketer looked exhausted, his eyes dead: “It was the 1000-yard stare.” When the Blues arrived in Hobart for the year’s last Shield match, the cricketer’s body rebelled. “It was freezing cold and pissing down,” Lawson recalls. “Maybe three players went into the indoor nets. Moises, as Moises does, batted far too long, then he wanted a bowl and third ball he pulls up feeling his groin.” Lawson groaned: “Oh, for f..k’s sake, you shouldn’t even be bowling.”

Again, Moises’ immediate sensation was relief, but this quickly gave way as the Blues were beaten out of sight. Returning home racked with guilt at letting his teammates down, he shunned company, dedicated himself penitently to physical recovery. It did nothing for his mental state, increasingly clawed by panic. When his groin recovered sufficiently for him to lead the Sixers in their first two games, he did so in terror of suffering an anxiety attack on the field. The gas cylinder finished the job.

On December 28, Moises spent two hours with De Moore, the last 40 minutes with Krista. De Moore urged him to consider antidepressant medication and take a break from the game. Prepared to accept the former, Moises was resistant to the latter. “You don’t understand,” he insisted. “I’m the captain.” Krista drove them home: “It was lucky she came. I couldn’t have done it. I felt 10 times worse leaving than arriving.”

They sat in a Clovelly cafe for half an hour in a desperate search for normality before Moises could bear it no longer, and he spoke to team doctor John Orchard, who urged him not to play that evening. Orchard, whose father is a psychiatrist and mother a psychologist, has developed a strong interest in mental health and the taboos around it. He reassured Moises: “This won’t count as a black mark against you. You’ll be supported all the way.”

At last, Moises rang Sixers coach Greg Shipperd. They agreed to meet early at the SCG. In more than 50 years’ cricket, Shipperd had never seen a player so distressed: “He went into a back story about having had these feelings for a long time, that he was at the point he couldn’t deal with them anymore. He’d be lucid for a bit, then he’d be in tears.” The coach took the decision out of Moises’ hands. “I’m shutting you down,” he said. “You’re in no shape to play. I’m going to walk you to your car and we’ll talk tomorrow.” Sixers physiotherapist Daniel Redrup, who’d witnessed the exchange, hugged Moises then rang Ed Cowan and told him: “Moises is in trouble and he’ll need someone with him.”

The Sixers support staff now discussed how to handle the announcement. Orchard thought it might be tactful to report a recurrence of Moises’ groin strain; Shipperd disagreed — and so, when consulted, did Moises. Two other players in the squad had quietly taken breaks from the game to deal with stress-related conditions in the previous two seasons. “They’ve owned it,” said Moises. “So should I.” It was agreed that his absence would be explained as arising from “personal reasons”.

The Sixers lost heavily. “I watched it at home,” Moises recalls. “It was terrible.” So was the next week. Moises could not sleep, could not eat; he paced at night, elaborately envisioning the worst: no career, for he could not bear it; no fiancee, for he was sure Krista would leave. He stayed in touch with Shipperd; he continued consulting De Moore and Whipper; Orchard and Cowan visited daily. “He was a walking skeleton,” says Cowan.

It was worst when the Sixers played without him. Moises feared going out, being seen, being judged. But the harshest judge was himself, for falling short of his own standards. Thinking he needed to intensify and accelerate his recovery, he had De Moore recommend a treatment facility, and checked in to the Northside Group clinic in St Leonards. He checked straight out, stricken with embarrassment. The people here had real problems: “I thought about going into a group session and saying: “Hi, my name’s Moises. I earn a lot of money, I own a beautiful house in Clovelly, I’m engaged to a beautiful woman who cares about me and yeah… my life’s shit.’”

Yet this also proved something of a turning point, for Moises chose to consider his condition as a kind of mental “injury”. Injuries, he reasoned, don’t always need a hospital, but they do need “rehab”. He would dedicate his every waking moment to getting better. He read voraciously on the subject of depression, and discussed it with friends and teammates when they called. He interrupted cycles of damaging thought by simple gestures such as swimming at Coogee, playing golf and walking the dog. He spoke daily to the Australian team’s psychologist, Michael Lloyd.

He even broached the subject with his father, of whose response he had always been slightly fearful. When Moises mentioned he was suffering depression, Alvaro grew upset, thinking it was all his fault. Moises hastened to assure him otherwise. Indeed, the experience had changed his sense of his upbringing. For the sake of his son, Moises reflected, his father had kept going, kept struggling, when at times it must have felt impossible. In its way, it was a heroic achievement.

Having ceased to be something Moises had to do, cricket started looking more like something he wanted to do. He rejoined the Sixers squad on a trip to Hobart without playing, remaining to one side, but to Shipperd he was clearly calmer. Finally, on January 13, he played again in Sixers colours, in a derby against the Thunder at the SCG. He took two wickets in three deliveries, and his unbeaten 18 from 13 balls included the winning runs from the final ball. De Moore was in the crowd: “I felt so proud for him, of him, because people didn’t know what he’d been going through. Relieved as well.”

The Sixers won their last four matches. Yet perhaps the key phase of Moises’ recovery was the resumption of the Sheffield Shield season, because it did not go to plan. Though he had surrendered the Blues captaincy, he scrounged just 32 runs in four hits, and was now staring at the poorest season of his career. All the same, he felt over the worst: “I thought: ‘Y’know, this is exactly what we’ve been working on. The sun’s still coming up in the mornings. They might drop me, but I hope they don’t, because I actually really want to play’.”

On February 24 at the SCG, he went to the middle against Tasmania and by the close had zoomed to 116 not out. “There was no way I would have had the mental skills to do that previously,” he says. In the season’s concluding games, he bowled as fast and as well as he had in two years.

Fixed? No, but better — happily married too, at last. And here, for all the trauma and toll, is a story of mental travail leavened with hope. Moises endured many gruelling years before being forced to seek help, but it was there for him, and cricket rallied round. “This could have gone on a lot longer and been a lot worse,” observes De Moore. “Moises was very open about how he thought, which made my task a lot easier.” But the stigma around seeking help remains, partly because of a sense that mental illness, by its seeming invisibility, is uniquely intractable. De Moore is anxious that this should be better understood — that while a strained mind is assuredly harder to treat than a strained hamstring, it can be addressed. “Major depression is a common condition,” he says. “None of us are immune. But it is also eminently treatable.”

At the Blues’ recent pre-season camp on the Sunshine Coast, coach Phil Jaques asked each player to bring an object that meant something to them. Many, inevitably, brought junior cricket bats. Moises brought a copy of The Courage to be Disliked, a work of popular psychology by Ichiro Kishimi and Fumitake Koga, whose words had provided solace at a low point (“Why is it necessary to be special? Probably because one cannot accept one’s normal self”). “I’m showing you this because I can’t show you my brain,” he explained.

Colleagues young and old listened intently as Moises described his self-interrogations, his dread and panic, his final breakdown. Afterwards, he had private messages from four squad members in their 20s — they too were wrestling with loss of focus and lack of enjoyment. Things can change, he told them. One need not suffer alone.

Lifeline 13 11 14; Beyond Blue 1300 22 4636

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout