Sport’s political power players are often ahead of the game

In an era of corporate virtue signalling, Usman Khawaja is a reminder that many of the moments of political sporting history we wistfully celebrate often come at great cost to the participants.

The move has the game and the player in uncomfortable territory and is a reminder that many of the moments of political sporting history we wistfully celebrate often came at great cost to the participants and were not so well received at the time.

Khawaja wrote “all lives are equal” and “freedom is a human right” on his shoes and, as The Australian revealed before the match, planned to wear them in the Perth Test. This has been deemed too much to stomach by the Australian and international cricket boards. He has since been ruled in breach of regulations for wearing a black armband without permission and again denied permission to wear the slogans on his shoes.

Stand by while a more anodyne and approved gesture is agreed upon.

The desire to keep conflict and controversy from the game is understandable, but it finds itself in a grey area now and flirting with hypocrisy.

Michael Holding found his voice during the Black Lives Matter protests and won the William Hill Sports Book of the Year prize for his book Why We Kneel How We Rise.

The West Indian great is scathing of cricket’s hand-wringing over the issue which he is monitoring from his home.

“I’ve been following the Khawaja fiasco and I cannot say I’m surprised by the ICC stance,” he told The Weekend Australian. “If it had been most other organisations that showed some semblance of consistency with their attitude and behaviour on issues I could claim surprise, but not them.

“Once again they show their hypocrisy and lack of moral standing as an organisation.

“The ICC regulations say re messaging ‘approval shall not be granted for messages which relate to political, religious or racial activities or causes’. So how the f..k people were allowed to take the knee for BLM and stumps were covered with LGBTQ colours?”

It is a similar point made by Khawaja and his teammates who are quick to say they support those issues but wonder why a phrase like “freedom is a human right” or “all lives are equal” can be banned. As captain Pat Cummins pointed out before the Test, it is hard to object to such sentiment.

Cricket allowed its participants to take a knee when the Black Lives Matter campaign was at its height.

The gesture was ring fenced and its duration marked by a series of whistles to ensure that the timing of the toss, the anthem, the start of the game and the like were not disturbed.

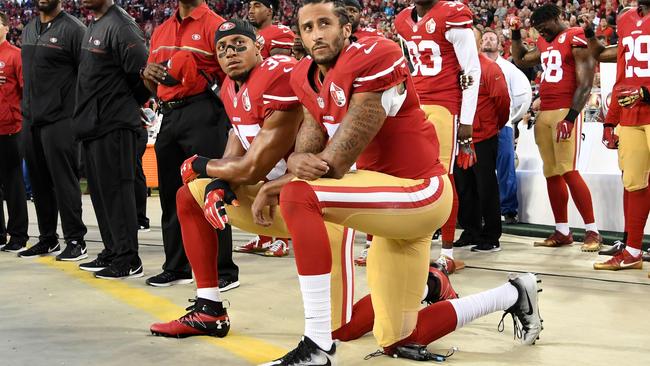

The kneeling gesture was first used by American footballer Colin Kaepernick. It became a common sight at sporting events in the US and around the world, but Kaepernick was nowhere to be seen and is apparently banished from the game for his role in the protest.

It was he who paid the price.

The 49ers quarterback had begun to sit out the national anthem, remaining seated on the sideline in during the 2016 pre-season.

“I am not going to stand up to show pride in a flag for a country that oppresses black people and people of colour,” he told a reporter. “To me, this is bigger than football and it would be selfish on my part to look the other way. There are bodies in the street and people getting paid leave and getting away with murder.”

The move caused outrage and Kaepernick decided that taking a knee would be a way of signalling respect for the anthem while marking the fallen, but it did little to alleviate the response from the hard right. Donald Trump called on clubs to sack anybody who followed suit.

“Wouldn’t you love to see one of these NFL owners, when somebody disrespects our flag, to say, ‘Get that son of a bitch off the field right now. Out! He’s fired. He’s fired!”

Nike backed Kaepernick, releasing an advertisement with the blackballed footballer that said “believe in something, even if it means sacrificing everything”. Others argued that his actions were protected by his First Amendment rights.

Kaepernick had inadvertently sacrificed his football career. He later took legal action against the NFL, accusing the team’s owners of conspiring to keep him from the game and was awarded a relatively small settlement.

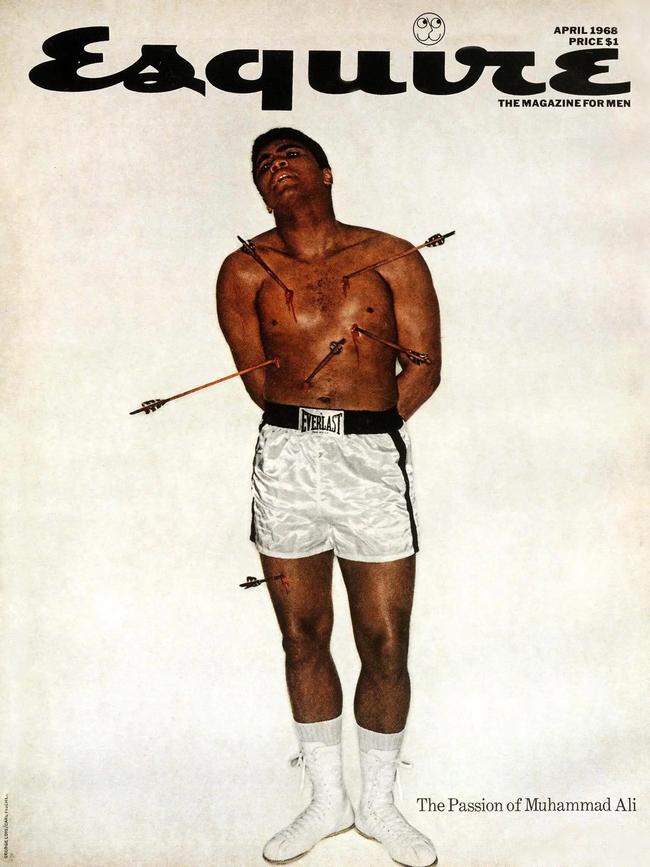

Muhammad Ali almost did the same when he refused to fight in Vietnam he was already off side with the American public for embracing the Islamic faith.

He missed three years boxing because of his objection to fighting in the war and while he is celebrated now for his stance, biographer Jonathan Eig observed that at the time he was berated by commentators and politicians as a “traitor”.

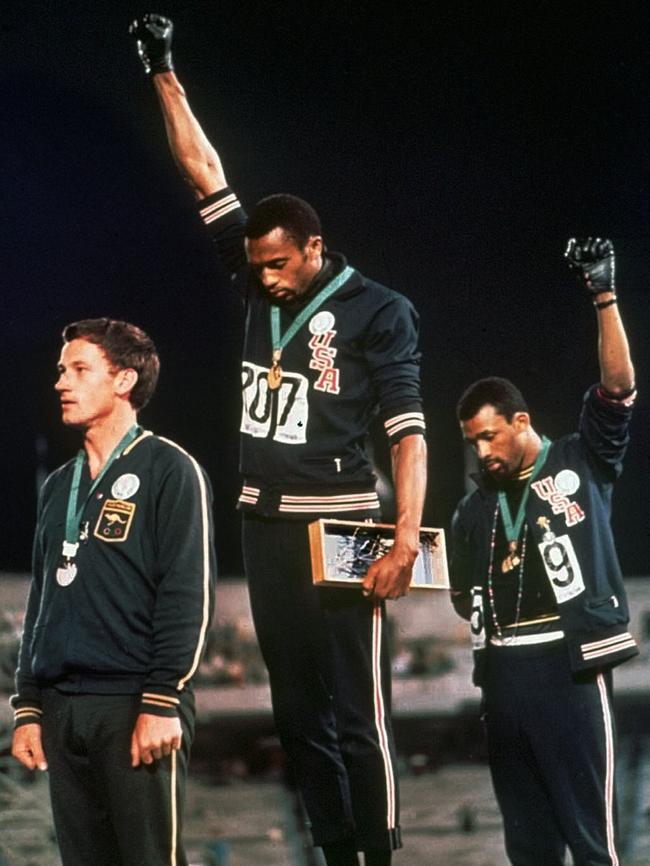

History has a misty-eyed view of the protest by gold medallist Tommie Smith and bronze medallist John Carlos after the 200m race at the 1968 Olympics, and Australian Peter Norman’s sympathetic alignment. But it cost all three greatly in the aftermath.

The International Olympic Committee demanded the US kick the athletes off its team and ban them from the Olympic village. When the US Olympic committee refused they threatened to ban the entire team and so the pair were expelled for a “a deliberate and violent breach of the fundamental principles of the Olympic spirit”.

They did not, however, have to return their medals.

The pair were, however, ostracised at home in the wake of the protest but managed to have relatively successful careers.

Norman was reprimanded and excluded by Australian authorities on return, but in 2012 the House of Representatives passed a motion of formal apology to the athlete and he was later awarded a posthumous gong by the Australian Olympic Committee. Smith and Carlos were pallbearers at his funeral.

To this day, however, the IOC stands by Rule 50 which prohibits “hand gestures or kneeling … as well as political messaging like signs or armbands” and claims 70 per cent of athletes agree with that stance. The US Olympic Committee, however, refuses to punish anyone who does protest, recognising that “human rights are not political” and that calls for equality are not divisive.

The Australian Olympic Committee recently endorsed Rule 50, reminding its athletes that they would be in breach of the Olympic charter if they protested at next year’s Summer Olympics in Paris.

Cricket, like all sports, loves a Kumbaya moment. The code has embraced equal rights for gay and lesbian athletes, endorsed the unsuccessful Yes campaign and has been actively engaged in a range of social issues.

It has not always sat well with critics but Cricket Australia argues it acts proactively so that the game is a “sport for all”.

The players and Khawaja argue acceptable symbolism has been ignored, even when it falls outside the rules. AJ Tye has been pictured playing the BBL with the gay pride colours on his sweatband and nothing was said. The team says it was given no say in the decision to cancel games against Afghanistan to support human rights there. Then there is the matter of Marnus Labuschagne having a biblical reference on his bat when religion is one of the proscribed areas when it comes to messages and equipment.

A game that can get itself in moral knots over a run-out at Lord’s has proven itself totally ill equipped for the times, but it could argue that world leaders find themselves similarly exposed.

In this era of sanctioned protests and corporate approved virtue signalling, Usman Khawaja was given to observe that “nothing worthwhile is easy” as he made slow progress toward permission to express concern over the humanitarian disaster in Gaza.