How Dean Jones defied heat, himself and the critics in Madras

Dean Jones loved a tale but there was one which needed no embellishment. His innings in the Madras tied Test will never be forgotten.

The first over he faced in Test cricket had, in its retelling, all the hyperbole of Hollywood. Bombs on the beaches and bullets whizzing past ears. Broken bodies and blood by the gallon. Joel Garner was bowling. His arm so long it reached above the sight screen and his hand so high it scraped the stratosphere. First ball was a bouncer and so were the third, fourth and fifth. The second delivery hit him with such force it made a “little hole at the front and a great big one at the back”of his torso. It was an “Exocet missile”. At over’s end he was shaking. Allan Border told him to toughen up, Joel put his arm round him and said “welcome to Test cricket”.

Dean congratulated him on his bowling.

Jones made 48 in a century partnership with Border that day at Port of Spain and rated it later as “my best-ever Test knock”. His skipper told him that if he could get through that he could get through anything as he’d never face bowling or conditions so difficult.

There is one Dean Jones story, however, that never required mayo. It is a tale so naturally tall it cannot be heightened, one whose drama reads as if melodrama.

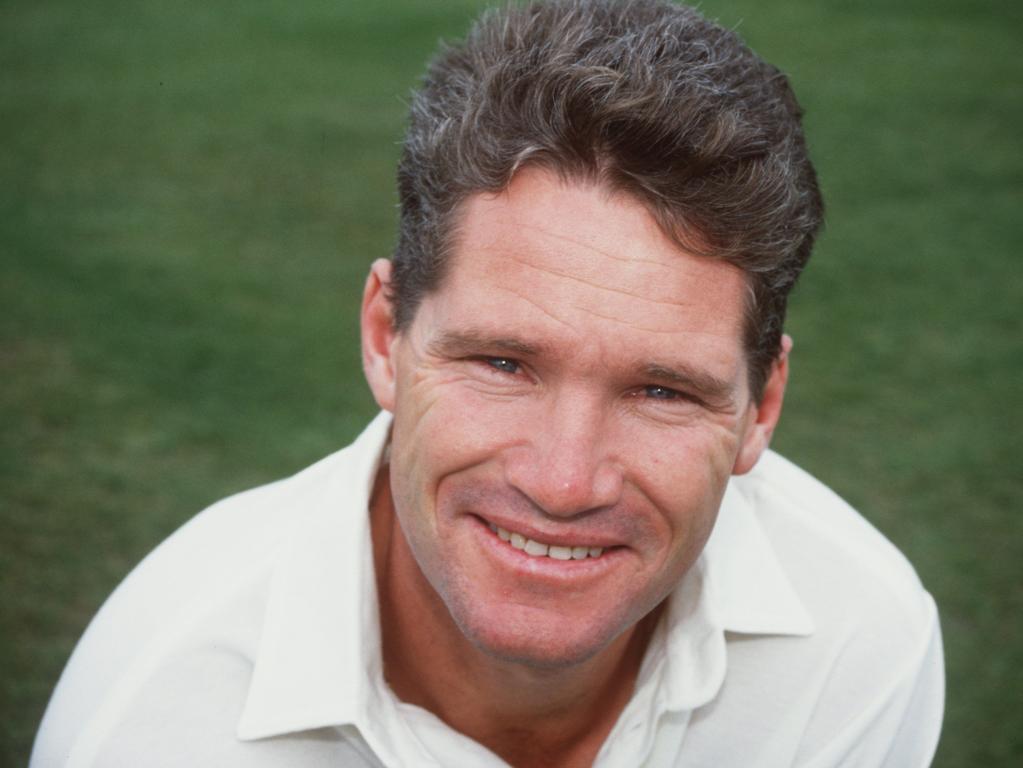

Dean Jones’ double century at Madras — now Chennai — 34 years ago this week is one of Australian cricket’s foundation stories. It exists in memory’s deceit, some hazy film footage, still photos and the accounts of those who witnessed it.

It is Everest conquered, the storm weathered, the sound barrier broken.

You didn’t have to be there or to be born then to understand the significance of those two days in India to know and understand what Jones achieved.

Bob Simpson called it “the gutsiest effort I have ever seen”. We may not have not seen but are blessed as one to believe.

Its magnificence is clear in its metrics alone: the length of the innings, the number of runs, the number of times he vomited and cramped, the number of times the tale has been retold, the way the game and the series is viewed as a turning point in the course of Australian cricket in India and the way it precedes a turning of fortunes.

Ashes and World Cup wins would follow, a feat few would believe possible as they surveyed previous performances.

Jones beloved Baggy Green was on his head for just the third time. It had been brooding in a cupboard since his debut and stayed there as the Victorian was overlooked for the next four series Australia’s rag tag cricket team would embark upon.

Selectors had given him two Tests in the West Indies in 1984 and then turned their back on him.

South Africa tried to lure Jones with sort of money that would set up a young bloke for life but his dad Barney ensured disappointment and frustration did not lead the impetuous youngster on the path to disaster.

Jones waited out his time restless and uncomfortable at being branded a one day player only, angry at being constantly overlooked.

When it seemed selectors had tried and tired of everyone else they turned back to the 25-year-old and chose him in the squad for the three Test tour of India.

On recall he sought the counsel of champions. Jones dropped in on Kevin Sheedy who pointed him toward Ian Chappell. He flew to Sydney and “over about 1000 Heinekens” Chappell told him some truths, including the fact he believed the Victorian was too brittle early in the innings to bat at No.3.

Jones claims the former captain filled his head with so much advice he woke the next day with a splitting headache.

His father Barney was a legend of Victorian cricket. Dean says that his dad was once convinced to fill in for a lower grade side and bat with his 14-year-old son a decade after retiring.

Barney, Jones claims in his first book, walked to the middle, took block then pulled out a handkerchief and approached the umpire. He then took out his false teeth, wrapped them in the cloth and asked the official to mind them while he batted.

His son says the ageing Carlton veteran struck the biggest six he’d ever seen . It is clear fruit didn’t fall far from this tree. His dad was a hard man but like his son had a soft side, both loved to garnish a tale and both shared an unyielding passion for the sport.

Barney wrote Jones a moving letter when he left for India in which he advised him find some acknowledgment of his teammates in success and to “keep up your confident approach whether it be in the field, or with the captaincy or with the bat. No confidence means no performance”.

The Jones’ men never lacked confidence and if they ever did hid it behind a blustering front of false bravado.

On the eve of the first Test Jones was summoned to AB’s room at the Taj Coromandel. Nobody had made a fist of the No 3 spot. David Boon and Geoff Marsh were tried but the captain wanted them to open, Wayne Phillips was used in the previous series against New Zealand, Border didn’t want to move up despite pressure to do so and he thought Jones might make a fist of it despite a poor start in the tour matches.

Border told Jones he believed he was capable of slipping into the critical batting position and making it his permanently. Jones says he walked out of the room feeling “10 feet tall”.

Maybe cricket had done him a favour by waiting until now. Australian cricket had reached its nadir in the three year’s previous winning just three of 24 matches.

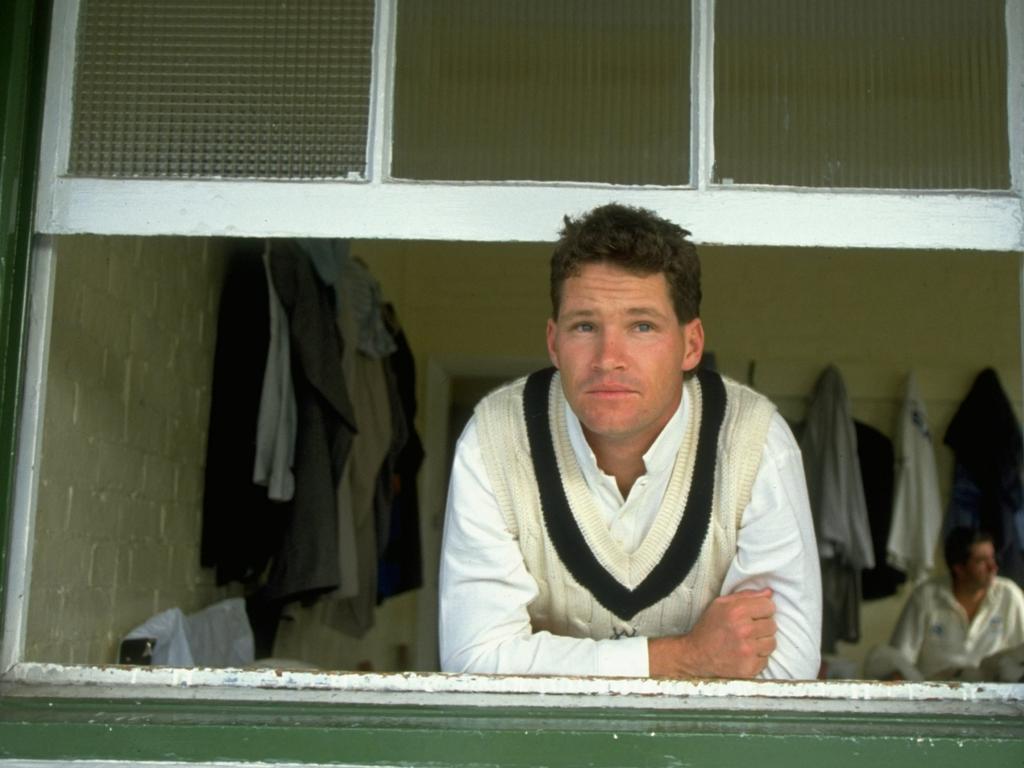

The esteemed cricket writer Mike Coward wrote he resembled a boxer with “dukes up was ready for a scrap”. Conditions were so awfully oppressive he’d had to change them before walking to the centre at 11.30am.

He batted through most of the day with David Boon but the gritty and slightly more experienced opener was brought undone by exhaustion and the new ball in the half light that precedes stumps.

Proving he had taken his father’s advice on board Jones said Boon’s 122 that day “was a bit overtaken by the drama of a tied Test and it isn’t commented on enough”.

The hitherto impetuous Victorian batsman had discarded his Hawaiian print, adopted Border’s hair shirt and dug in.

His first Test 50 took four and a half hours. In Lancashire he’d once scored 76no on coming in with seven overs left in an innings.

His first day at the crease in India included just two fours. Australia were 2-211 at stumps and Jones 56no.

This was an era before sports drinks and science. That night Boon escorted the batsman to the bar in the hotel where he had trained the staff to have the beer icy cold. Jones rehydrated in the traditional manner.

Boonie told him some people were born to play cricket for their country and Jones was one of those people. The words and the beer helped a little but he was anxious.

He didn’t sleep that night, he didn’t eat breakfast that morning.

He continued batting with nightwatchman Ray Bright who was battling illness and the gruelling conditions.

Bright batted for 80 minutes but became so distressed by the heat Jones said the spinner collapsed in tears in the dressing rooms. Coward says Bright, who was panicking and yelling “I can’t get air, I can’t get air” had to be restrained by the team physiotherapist Errol Alcott.

Jones was now batting with Border and determined to demonstrate first hand to his captain that his faith in him was not misplaced.

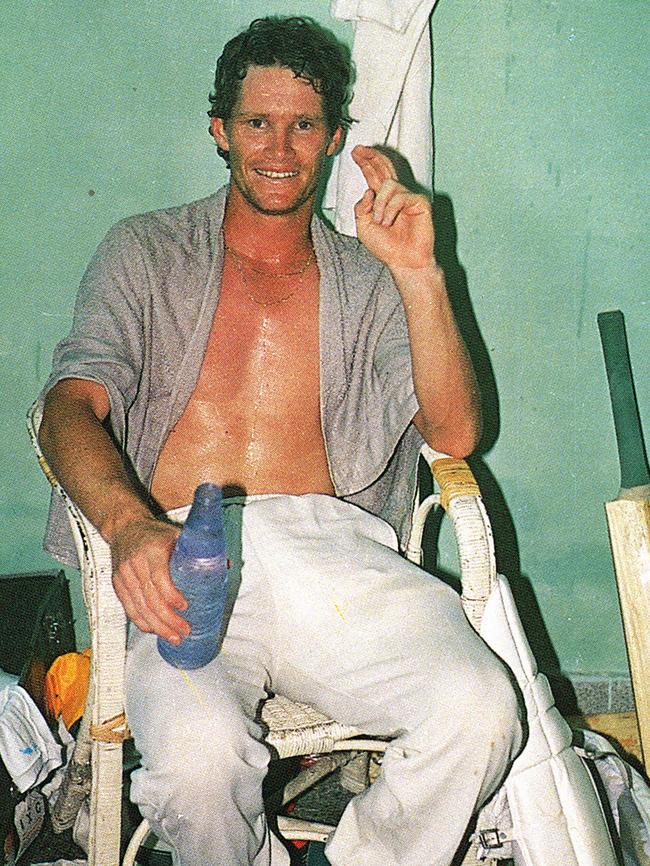

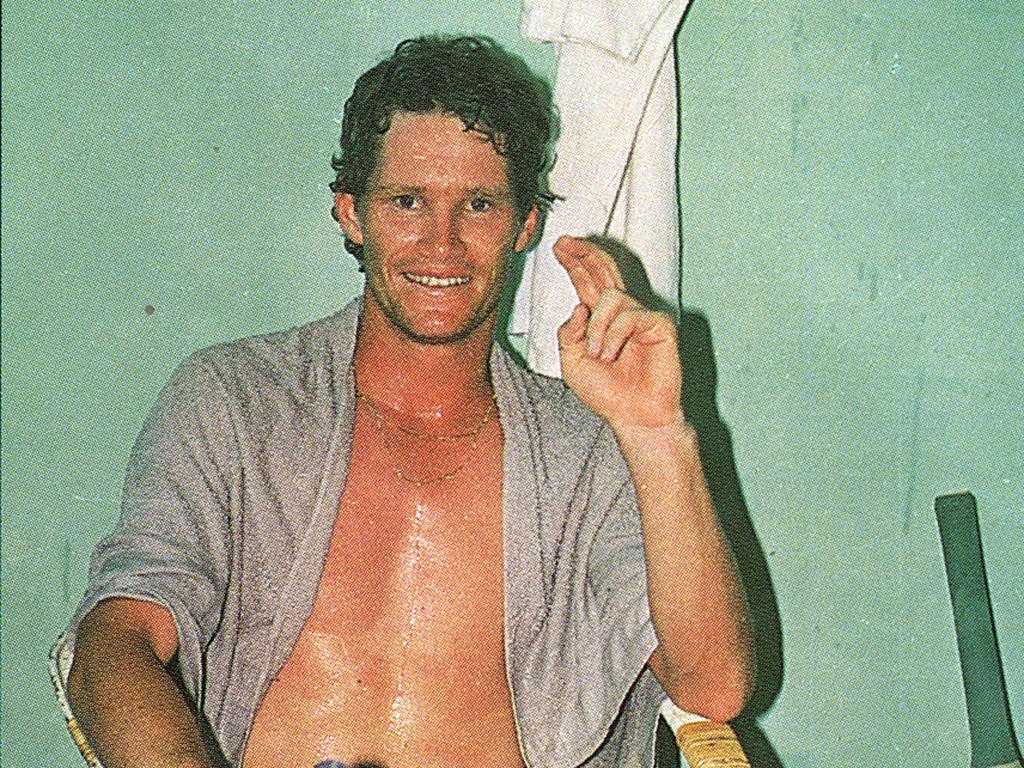

He started to cramp and vomit as he reached his maiden Test century, but a handshake from the veteran re-energised the batsman who’d now been at the crease for five hours and 35 minutes.

His health, however, was deteriorating.

Coward was watching from the open press box, typing an account he would later send through via telex from a small room below.

“As he moved beyond 150 his body began to shut down,” he wrote in Beyond the Bazaar. “Time and time again he drew away from the wicket, pitched forward and, body shaking, disgorged the fluids and mineral replacements ...”

He doesn’t remember anything of the innings at this point apart from parking his feet and deciding to swing from the crease somewhere around the 150 mark.

At 170 the situation things were escalating.

“I didn’t think I could go on; I must have vomited 15 times and I had cramps and I was trembling. I was holding up the game,” Jones wrote in his book Deano — My Call.

Cue the infamous exchange.

“I’ve had a gutful,” he said between spasms. “All right,” Border replied. “If that’s the way you feel, let’s get a real Australian out here. A Queenslander.”

Few cricket conversations are as well known or as often repeated.

His second 100 came form just 99 balls for he couldn’t run anymore, by tea he was 202 but had been exposed to the elements so long that the management and medical staff tried to insist he not return to the crease.

In the break Jones’ teammates undressed him and placed him under a shower. After some confusion the delirious batsman chose to continue and was dressed again by his teammates who sent him to the middle without a thigh pad or protector.

He was, mercifully, dismissed 14 minutes into the third session.

“My new clothes were already like dish clothes and the water was squelching out of my boots,” Jones said. “I had batted for eight hours and 24 minutes and hit 27 fours and two sixes. It’s in Wisden so it must be right.”

An ice bath and two soft drinks were enough to fool Jones that he was all right, but the next thing he was aware of was waking in a hospital.

He’d passed out and eventually been rushed through the streets of Chennai in the back of a rattling ambulance, bouncing from the bed at every turn. He recovered quickly at the hospital and returned to the hotel at midnight.

Everyone who has ever been on the road with Dean Mervyn Jones and known the endless youthful enthusiasm he brought to every day wished the same could have been written about the ambulance trip Jones took through Mumbai’s crowded traffic Thursday night 34 years and two days later.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout