Hall of Fame honour for Australia’s original cricket superstar

There is so much about the first indigenous cricketer inducted in the Australian Cricket Hall of Fame that’s lost to time. But what’s recoverable provides a reasonable case for his recognition.

There is so much about the first indigenous cricketer inducted in the Australian Cricket Hall of Fame that’s lost to time: his biographical history is scant; his inmost thoughts were never recorded. But what’s recoverable provides a reasonable case for his recognition, also as the hall’s earliest cricketer and first non-Test player.

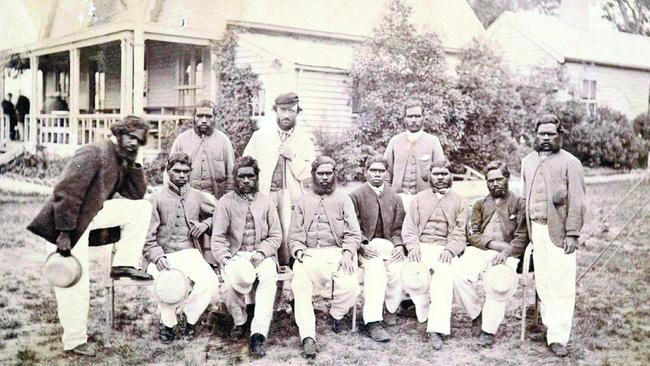

For much of the time Mullagh was his people’s outstanding allrounder, it should be understood, there was not so much Australian cricket as cricket in Australia. When Mullagh and his peers toured England in that fabled indigenous team of 1868, they were neither representing a nation nor blazing a pioneering trail: in some ways, to borrow the title of Bernard Whimpress’s 1999 history of cricket’s Aboriginal quotient, theirs was a passport to nowhere. Still, Mullagh’s story is so remarkable as demand retelling, and deeper and longer than many realise.

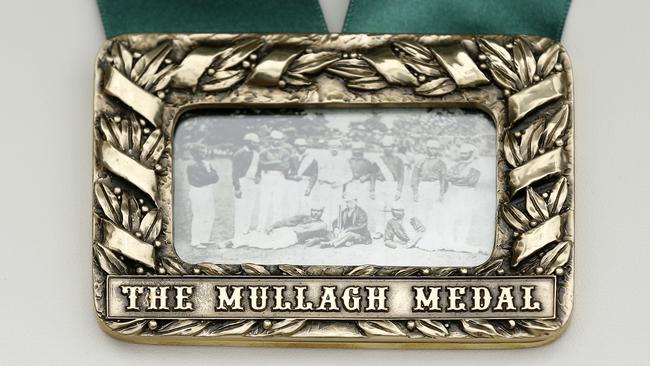

Monday’s announcement complements the earlier decision by the Melbourne Cricket Club to mint the Mullagh Medal for the player of the match in the Boxing Day Test, which commemorates what must be one of cricket’s most astonishing matches: when MCC welcomed “Ten Aboriginals with T.W. Wills” on December 26 and 27, 1866, drawing 12,000 curious spectators.

The team came in lieu of an English side that the club had tried but failed to lure to the colony. It also expressed a strong local pride in the Western District, which four years earlier had campaigned to secede from Victoria as Princeland, and an anthropological curiosity, articulated by the team’s pastoralist impresario William Hayman: “These men are literally and truly the last of their race, and in a few years the Aboriginals will have ceased to exist in the West Wimmera district.”

Still, an image of the team, garbed in white, was published ahead of the game on the front of The Australian News for Home Readers, at a time when an Aborigine was likelier to be depicted in a loincloth with a spear. Mullagh’s second innings of 33 was then described by The Age as “one of the finest innings ever witnessed on the Melbourne ground. Whether in defence or hitting power, he is equally great, and the better the bowling the better he seems to like it.”

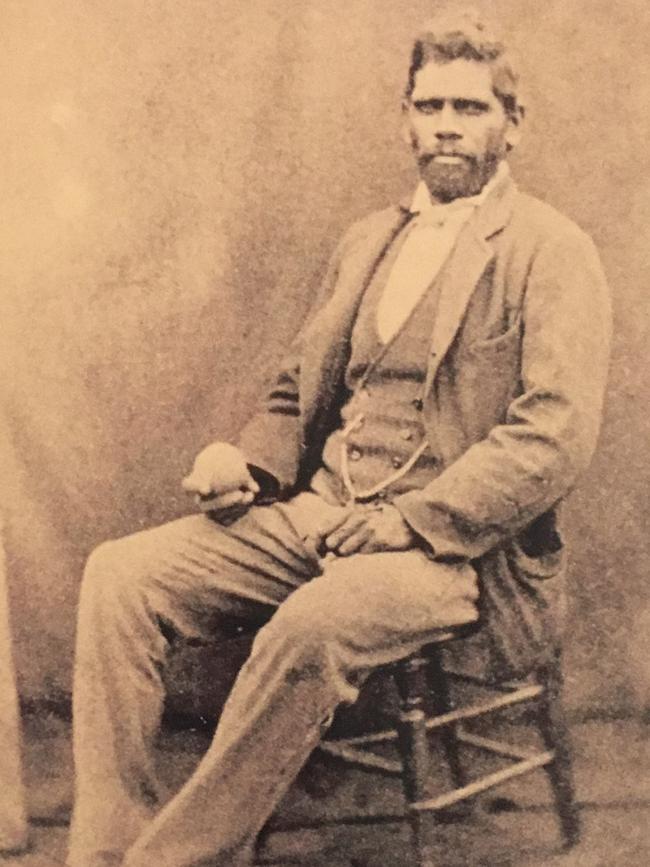

Mullagh’s feats on the subsequent indigenous tour of England beggar belief even today: 71 innings for 1698 runs at 23.65, 245 wickets at 10 from 7508 deliveries, in a strange, cold, faraway land. He earned praise from W.G. Grace for an elegant 75 at Lord’s when the XI led Marylebone on first innings, and from the country’s leading fast bowler, George ‘Tear ’em’ Tarrant, who was sufficiently intrigued by Mullagh to request permission to bowl to him in the nets at lunch one day.

The story was recounted by the team’s captain Charles Lawrence to the former Test cricketer turned cricket correspondent of The Australasian, Tom Horan: “Directly Mullagh was asked, he said, ‘I’ll bat against him.’ and he kept Tarrant hard at it all through the luncheon-hour.

“Johnnie, in the excitement of practising against the great bowler, forgot all about his luncheon, and played him for the full time without being bowled. Tarrant, after the practice was over, told Lawrence that Mullagh was undoubtedly one of the finest batsmen he had ever bowled against.”

Mullagh was 28, an

d in his cricket prime, but means of pursuing the game were elusive. He played as a professional for Melbourne CC in 1869-70, finishing second in the batting averages (34.5); he played a single game for Victoria against Lord Harris’s English team in February 1879, top scoring with 36, winning praise from The Argus for his “cool artistic style” and “judicious treatment of dubious balls”.

After the latter innings, Mullagh was presented with a bat by the English amateur A.N. Hornby, and a purse of £50 was collected for him by the former Victorian premier J.G. Francis — staggering munificence in the context of the times.

Between these engagements, however, Mullagh was largely confined to the Western District, where he shared a hut with his favourite dogs and worked mainly as a rabbiter. The Aboriginal Protection Act of 1869 was also steadily turning his people into mendicants.

Yet it’s possible the most remarkable cricket Mullagh played with is the least documented. He continued, until just a few months before his death in 1891, to represent Harrow, in a team consisting otherwise of white settlers — so successfully that the club, having won three consecutive premierships, was expelled from the local competition.

What must this have been like, to play cricket alongside people whose culture had reduced the indigenous population of the district from the thousands to the hundreds? What we do know is that Mullagh’s prowess was sincerely admired, and that mourning at his passing seems to have been genuine and heartfelt.

He was buried with a bat and stumps by club mates; he was furnished with a fine grave, which vaunts him as a “World Famed Cricketer”, and an impressive memorial, a pink granite obelisk enumerating his statistics. He was saluted in the Hamilton Spectator with an unsigned epic poem, according him the status of a colonial hero for his deeds at Lord’s. A stanza reads:

Of his powers in the cricket field

Victoria knows, and shall surely say

How he strove for her, nor did he yield,

Until his score on one famous day

Stood highest of all, when England’s might

Knew Mullagh’s strength in that well fought fight

Part of this, no doubt, was the sense of a whole world passing, to which the newspaper also attended in its well-meant tribute: “We may have another Grace, but never will Mullagh’s reputation be surpassed by any of his race, for none, in a few years, will remain to show that once this great land of ours had a people of its own who, but a short half-century ago, were monarchs of all they surveyed.”

The people, however, did not pass, and the reputation remains one to be inspired by.

Johnny Mullagh, of course, was only his white fella name. He was born Unaarrimin in 1841. Mullagh was the Western District station he worked on, 16km north of Victorian town Harrow, which was named in turn for an Irish village. Johnny? Who knows?