Fifty years on from the first ODI, the game that changed cricket

Fifty years ago this week, a meeting took place in Melbourne that changed cricket. It propelled the sport into the modern world.

Fifty years ago this week, a meeting took place in Melbourne that changed cricket. It propelled the sport into the modern world and transformed the economics of the game.

It happened on what was supposed to be the third day of an Ashes Test at the MCG; steady rain had prevented a ball from being bowled since the England captain Ray Illingworth won the toss on the first morning. In desperation, the Australian board, led by its chairman Donald Bradman, convened with David Clark, manager of the English touring team, and Gubby Allen and Sir Cyril Hawker, respectively eminence grise and president of MCC, to see what could be done.

With no prospect of a positive result, but with a holidaying Melbourne public eager to see action and a lost Test equating to a deficit of about $140,000, the audacious decision was taken to abandon the match and stage a contest consisting of 40 eight-ball overs per side (eight-ball overs were the vogue in Australia) between an England XI and Australian XI - now regarded as the first one-day international.

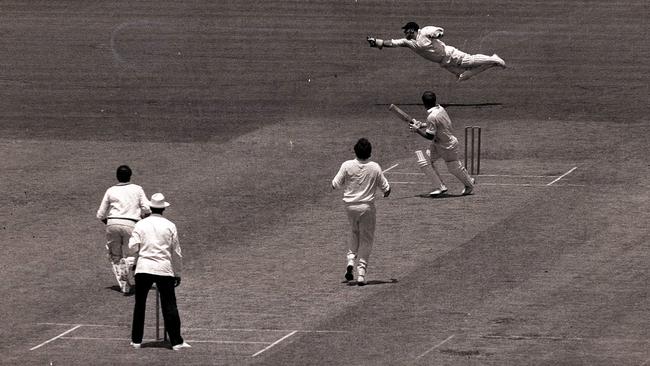

Despite a predictably slow pitch that contributed to only one six being hit (by Ian Chappell, whose 60 navigated Australia to a target of 191), the match on January 5, 1971 was a huge success.

It was thought 20,000 may turn up. In the event, the attendance was 46,006, dwarfing anything achieved in the Gillette Cup and John Player League, the popular one-day county competitions in England that gave life to cricket’s short form. Receipts totalled a healthy $30,000

Some England players were unhappy at being forced to play this extra fixture, plus an additional Test in Sydney at the end of the series at the expense of some minor fixtures. Only after a heated meeting in Illingworth’s hotel room was assent given. In reality they had no choice: tour contracts were framed by length of mission rather than number of engagements. Fortunately, a hurried sponsorship deal with Rothmans meant the teams received an additional $1000 each.

Seasoned observers instantly read the runes. At the post-match presentation, Bradman told the crowd: “You have seen history made.”

John Woodcock in The Times noted: “So successful was the one-day cricket match played here today … that one is bound to wonder what it may lead to.”

He added: “An entirely new and separate tournament between all the cricketing countries, consisting only of one-day matches, may have been brought nearer by the success of today’s promotion.”

A plan to play a sixth Test on Australia’s tour to England in 1972 was duly scrapped. In its place were held three ODIs (combined attendance 55,000). At the ICC annual meeting the next year, English delegates — possibly galvanised by an equivalent women’s event already being under way — proposed staging a World Cup. It was held in 1975 and proved a triumph. Australia’s defeat by West Indies in the Lord’s final was a contest of classic stature and 15 games generated significant profits. Cricket was on to a winner.

Initially, growth was slow. After 10 years only 103 one-day internationals had been played anywhere, and 82 of these were in England or Australia.

By then, though, the game was experiencing the consequences of Kerry Packer’s World Series in the late 1970s. He saw ODI cricket for what it was: the perfect vehicle for consumerism. People wanted to go to the game after work or watch on TV at prime time, so he created day-night cricket, and they wanted to see runs scored, so he invented fielding restrictions. He monetised the breaks between overs by selling space to advertisers.

Other factors contributed to boomtime. India’s unexpected World Cup win in 1983 created frenzied interest on the subcontinent, where previously there had been apathy. Satellite TV took off, and with it offshore venues such as Sharjah, which facilitated the growth of matches between India and Pakistan, and gambling.

Administrators could not think up fast enough excuses to hold one-day tournaments. How about celebrating the 150th anniversary of the founding of the state of Victoria? Seven teams turned up in 1985 for that one. Surely we must mark the centenary of the birth of Jawaharlal Nehru? Count me in, said everyone in 1989.

From 1981 to 1990, 556 ODIs were played; from 1991 to 2000 another 1003. The tally swelled to 1,16 from 2001 to 2011 before falling back to 1189 since 2011 — reflecting the competing demands of Twenty20.

A few, such as Sachin Tendulkar, grew rich from their parts in sustaining the ODI success story, but many players grew disenchanted with the relentless schedule and the suspicion that they were seeing little of the money pouring into board coffers.

By the turn of the century, some teams were playing upwards of 40 ODIs a year in addition to extensive Test commitments. Little wonder some took the money of corrupt bookmakers and gamblers in return for fixing games that carried little context or meaning. The Hansie Cronje scandal of 2000 compelled authorities to act by improving pay and making matches count towards ranking systems and qualification for major tournaments.

On the field, ODI cricket has lent itself to the pursuit of marginal gains and as such has been in constant need of regulatory refinement. Rule makers have had to arbitrate on what constitutes a wide and a bouncer, react to Mike Brearley placing 10 men on the boundary at the end of a match in Sydney in 1979, and Greg Chappell instructing his brother, Trevor, to bowl underarm to win a game against New Zealand in 1981.

Where would one-day cricket’s credibility be, too, without the introduction of the Duckworth-Lewis method in 1997 for resolving rain-affected games?

Players have relished finding method in the madness. Jonty Rhodes, Ricky Ponting and Paul Collingwood raised fielding standards to new levels; Mark Greatbatch and Sanath Jayasuriya fashioned pinch-hitting; Kevin Pietersen invented a new stroke; and Saqlain Mushtaq and Muttiah Muralitharan developed doosras.

The super-talented have shown how broad the canvas might be, but most games are unmemorable. Administrators have sought to keep things fresh, introducing power-plays, supersubs, Super Overs and the like, but for all the gimmicks, and much of the mundaneness, it is a format that has defied obituary writers.

T20 may have stolen many of its clothes, but India’s win in the 2011 World Cup, and England’s astonishing victory on boundary countback over New Zealand in the 2019 final, both reaffirmed that the ODI still has a place in the world.

The Sunday Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout