CricViz: Australia’s pace battery dominates world cricket, but must defy history to win India series

Australia’s pace attack is the most lethal in world cricket, proved by the way they dominated India in Adelaide. But they must defy Test history if Australia is to win the Border-Gavaskar Trophy.

And then, the comeback was on.

After defeat in Perth, Australia roared back with an emphatic 10-wicket win in the second Test, levelling the Border-Gavaskar series as we head to the Gabba.

But if Pat Cummins’ side do take this momentum forward and win out from here, it’ll be something of an anomaly.

As has been mentioned plenty of times in recent weeks, the last time Australia won a Test series having gone one-nil down was the 1997 Ashes, a six-match series where Mark Taylor’s team pulled it back having lost the opener at Edgbaston.

They aren’t unique in this pattern – comeback wins across a series are rare full stop – but in an era where they have either been the best in the world, or aiming to be, it’s a quirk.

Since the start of the ‘sandpaper’ series, Australia have played seven ‘long’ series (four or more matches), with two visits to England, a visit apiece to South Africa and India, plus three home series (India twice, and an Ashes).

In those series, it is undeniable that they perform better in the earlier matches. Their results start strongly, often with highly impressive performances – Edgbaston 2019, Lord’s 2023 – and then drop off.

By the third game of the series they are winning less than 30 per cent of their Tests.

The most notable of these drop offs was the 2020/21 Border Gavaskar Trophy.

With the series level at 1-1 after two Tests, Australia created two excellent winning positions,

needing to bowl India out in 130 overs at the SCG or defend a target of 407 at the Gabba.

Infamously, they failed to convert either of these chances and the series was lost.

In that instance much of the blame was placed on the flagging bowling attack.

The big four – Pat Cummins, Josh Hazlewood, Mitchell Starc and Nathan Lyon – had all played in every Test and looked undeniably leggy.

On the final day at that Brisbane Test, all three seamers appeared to be down on pace, raising questions around the rotation – or lack thereof – over the course of the series.

So as we move to Brisbane once again, it’s a fitting time to reflect on how true these assumptions are around the bowlers, how urgently rotation is required and is it true for any bowler in particular?

Let’s start with Starc, where debate feels most heated.

Inherently a very mercurial bowler, the left-armer doesn’t have the nagging accuracy of his teammates to fall back on when movement or speed is lacking, so his conditioning is key.

Interestingly, in simple terms there is no evidence that Starc’s speeds drop off across a series. His average pace in these recent longer series have remained at around 142kph in almost every Test.

More forensically, even if you look at the speed of individual spells, breaking them down by the day of the match, there’s precious little to say there’s a major issue here for Starc.

What is an issue is that while his speeds remain constant across a series, his average does not.

In the first three Tests of longer series, Starc averages 25.89, but at the sharp end of the fourth and fifth, he averages 40.10.

There might be an element of venue preference at play, skewing the figures slightly – Starc famously doesn’t like bowling at the SCG, a ground where he averages 44 and which hosts a lot of final Tests – but it holds up away from home as well.

As series wear on, Starc doesn’t get slower, but he becomes less effective.

For the captain, there’s a similar issue, albeit less concerning.

Cummins’ speeds also remain constant across the series, but his returns do marginally fall away.

In those opening three Tests Cummins averages 21.33, rising to 26.77 in the final two matches. It’s not a problem per se, given an average of 27 is still outstanding, but it does reinforce the trend.

Josh Hazlewood stands slightly aside, given his injury record has actually given him a lighter workload.

But even for him, the pattern stands, with an average of 24.30 in the opening stages falling away to 34.63 at the back end.

Again, no noticeable change in speeds, but a deterioration in performance.

The numbers are concerning for the hosts, no question.

While India’s bowling attack does look alarmingly reliant on Jasprit Bumrah and to a lesser extent Mohammed Siraj, the batting is simply out of form – there is quality there.

As the miles go into these legends’ legs, and the Indian batters get progressively more familiar with the conditions, you do wonder if Australia’s dominance with the ball at Adelaide is replicable as we move east.

Arguably, this is the price of greatness.

Cummins and coach Andrew McDonald have been content to stick with the established stars, the big three plus occasional Scott Boland, for the best part of 10 years now.

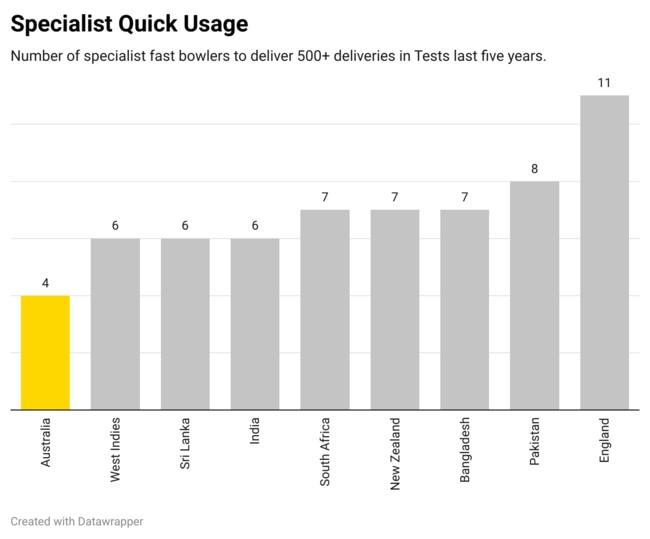

Since the end of the 2019 Ashes, those are the only specialist quicks to play Test cricket for Australia, supported variously by Mitchell Marsh and Cameron Green.

Their schedule is not the busiest around, but even with that considered it’s notable how when

compared to other sides, Australia rely enormously on a very small number of quicks.

Which is to say, there’s not much which can be done about this now.

Had Australia rotated more in the previous 18 months, given opportunities to the Shield stars and youngsters, then they may be in a stronger position, either from resting the big three mid-series, or injecting fresh legs in the latter stages.

However, they are not in that position. That core of Hazlewood, Cummins, Starc and Boland will be what sees them through the rest of this series, tasked with winning back the

trophy they’ve not held since 2017.

And for all the reasonable concern, if you’re relying on an attack with 600 wickets in Australia at a tick under 23, then you’re not in a bad spot.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout