Cricket: Would Australians take a knee like West Indies players plan to do?

If Australia were playing cricket now, would players take a knee during the anthem as football players have done?

If Australia were playing cricket now, would players take a knee during the anthem as football players have done? Would they appear with a Black Lives Matter message on their shirts, as the West Indies will in the forthcoming series against England?

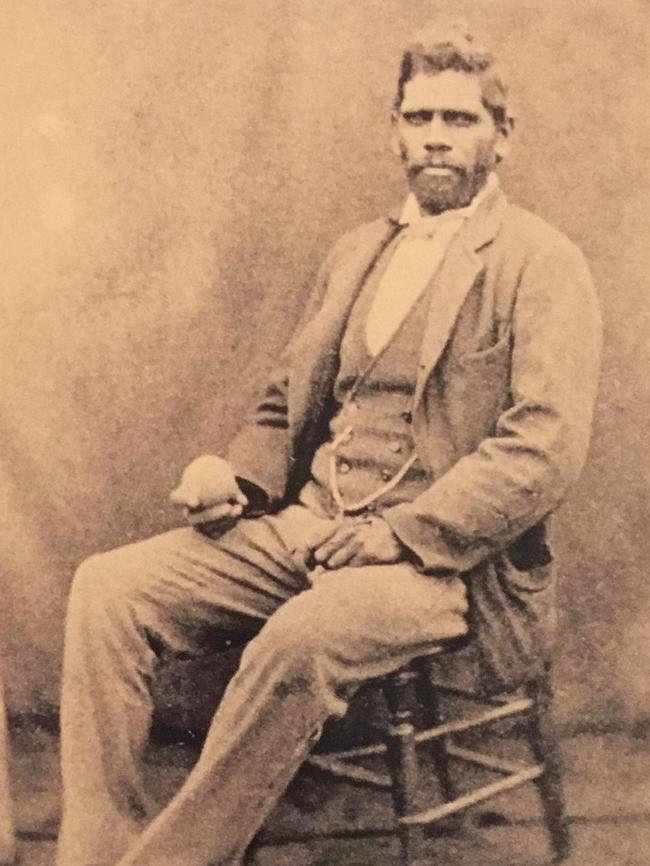

The Australian men’s and women’s teams wore Aboriginal artwork on their collars during the Ashes last year in recognition of the pioneering 1868 indigenous cricket side. There are plans for the players to wear an indigenous-designed uniform for the T20 series against India in October and this year’s Boxing Day Test will see the inaugural presentation of the Johnny Mullagh Medal to the player of the match. Mullagh was a star of early indigenous sides and captained the first tour of England.

Cricket Australia plans to consult its Aboriginal Advisory Committee and others about further actions given the political climate.

The AFL players’ gesture in round two was driven by the players and proof of the problems it sought to recognise was at hand soon after with subsequent racist attacks on several Aboriginal players, most notably Eddie Betts.

Australian cricket thought it would escape the worst of the financial impact of the pandemic because it was in winter recess, but was quickly proved wrong.

But it has managed to sit out the initial intensity of the political situation because there has been no cricket and is none scheduled for some time. In England, West Indies captain Jason Holder is aware the situation is more immediate and the visiting side is keen to make a gesture of solidarity.

“This is a pivotal moment in history for sports, for the game of cricket and for the West Indies cricket team,” Holder said.

“We have come to England to retain the Wisden Trophy but we are very conscious of happenings around the world and the fight for justice and equality … we know of the rich and diverse history of West Indies cricket and we know we are guardians of the great game for generations to come.

“We did not take our decision lightly. We know what it is for people to make judgments because of the colour of our skin, so we know what it feels like, this goes beyond the boundary. There must be equality and there must be unity. Until we get that as people, we cannot stop. We have to find some way to have equal rights and people must not be viewed differently because of the colour of their skin or ethnic background.”

The ICC, usually anxious about political gestures, concedes this is one it is comfortable with.

Members of the Australian men’s side said they had not been together to discuss the matter, but are all aware of what is happening.

Pieces published by Britain’s Daily Telegraph and ESPN Cricinfo have examined racism in English cricket and tried to explain why there are only nine players of colour in the county system.

Lisa Sthalekar, an Indian-born Australian cricketer, believes questions need to be asked about why our cricket teams do not represent the cultural variations within Australian society.

“Race has been an issue for a number of players and I think from a cricketing point of view we have accepted it and kept it quiet and moved on,” she said.

“It has affected players, some tremendously, maybe not like in the AFL but the conversation still needs to be had until we get to a point of equality until players are not looked on as different.”

The highest-profile incident in Australia involved the alleged abuse of Andrew Symonds by India’s Harbhajan Singh in 2007-08.

Michael Holding told Cricinfo that the main problems he’d encountered had been with crowds.

“The racial abuse I have experienced came mostly from the crowds. I wasn’t abused once by an Australian or English player,” he said. “The crowd would pile it on, of course, and that’s why I believe racism is a societal problem.”