Alan Davidson: the acme of the Australian cricketer

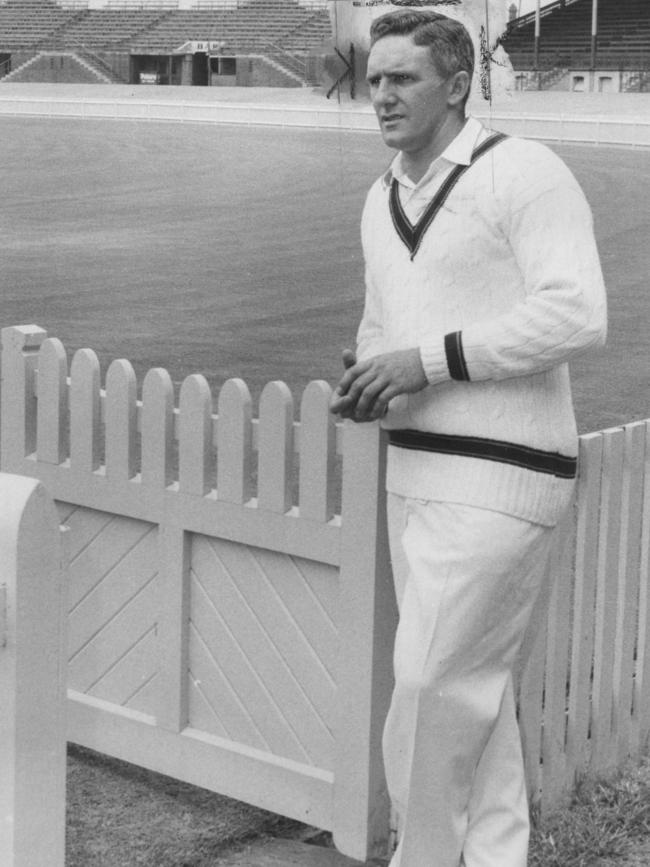

From out of the bush near Gosford, Alan Davidson was an athletic, attacking all-rounder, who bowled fast, hit hard and caught unerringly.

First a favourite personal memory of Alan Davidson, who has died, aged 92. In London ten years ago, I attended an International Cricket Council Awards, where Davo was added to its Hall of Fame in the company of the towering, saturnine Curtly Ambrose and wiry, wily Belinda Clark.

They flanked Davo like the most unlikely honour guard, and how he loved it, the audience also: there was all cricket here, and you could see them chatting away like long separated friends. Which was very Davo – the only people who weren’t his mates were those he hadn’t yet met.

A bit later I was asked, at short notice, to interview Davo on stage. I hadn’t the scrap of a note, but needn’t have worried: we could still be talking. Not only were his cricket anecdotes sharp and funny, but he recreated the London of the 1950s, as he had first found it, to the extent that you half expected the picture to dissolve and to find yourself back there.

Alan Davidson was the acme of the Australian cricketer: from out of the bush near Gosford, an athletic, attacking all-rounder, who bowled fast, hit hard and caught unerringly. He was steeped in the game by a cricket-loving timber-cutter grandfather born in the year Australia first toured England, the bold, bare-headed drives of his career a testament to the strength of the old man’s admonition to ‘play with a straight bat’.

He laid out his own pitch on a hillside, flattening the turf with a mattock, wheeling away for hours at stumps fashioned from gumsticks. He learned to throw by challenging himself to hurl oranges fallen prematurely from a tree towards a railway line 100m away.

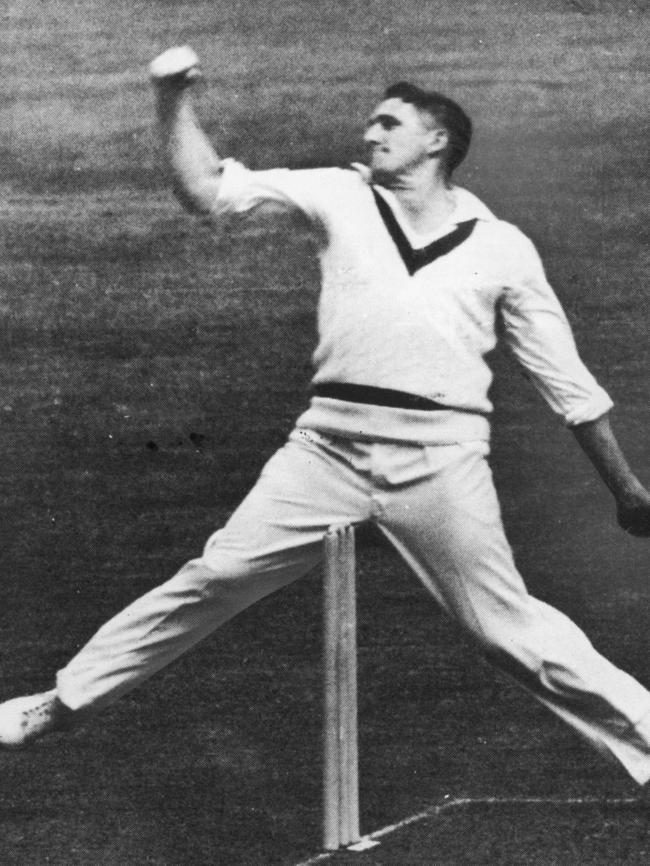

One attribute in particular made him unusual: Davidson was left-handed. There was in his era simply nobody comparable. He was quick. His run-up was economical, his action beautifully fluid, his swing abrupt and late. At his peak, he was like Ben Lexcen’s wing-tipped keel – a unique and somehow inimitable Australia advantage.

The peak, to be true, was a while coming. Davidson’s career splits visibly into two, his first dozen Tests being only a loose translation of his talents: 317 runs at less than 19, 16 wickets at 34.

So reticent was Davo, it’s possible he was inhibited by playing alongside cricketers he never ceased to revere: Keith Miller, Ray Lindwall, Arthur Morris, Lindsay Hassett. He certainly suffered from a captain, Ian Johnson, who saw in him a left-arm slow bowler in the making, at a time when they were thin on the ground.

It wasn’t until all the foregoing had exited that, suddenly, Davidson fulfilled the prophecy of Sir Donald Bradman, who after seeing him the first time thought he had ‘the greatest potential in Australia’.

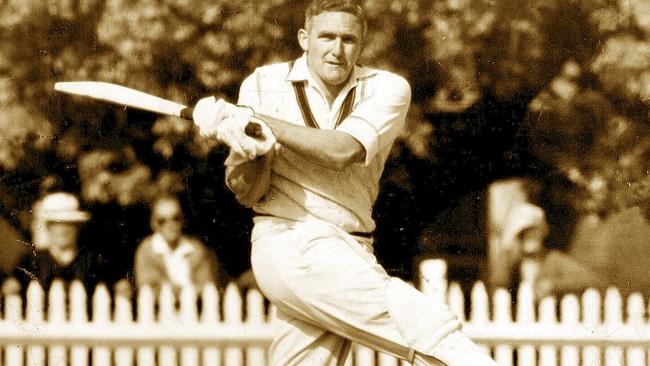

In his last thirty-two Tests, starting with the 1957-8 tour of South Africa, Davidson made 1011 runs at 27.3 and claimed 170 at 19.2, in all countries and climes. On dustbowls in India and matting pitches in Pakistan, Davidson took 41 wickets at 18.

Ashes Tests, of course, were the acid test, and on English batting at Melbourne in 1959, Lord’s in 1961 and Sydney in 1963 he acted like a universal solvent.

The English playwright Ben Travers, whose cricket watching spanned eight decades, grudgingly thought Davidson peerless: ‘From my seat in a stand as an England supporter, no Australian fast bowler – McDonald, Gregory, Lindwall, Keith Miller, even Lillee – ever put the wind up me as Alan Davidson did … No fast bowler in Tests against England ever kept my behind so agitated in its seat.’

The playing career, of course, ended fifty-eight years ago, and it may seem strange to still be extolling someone whose sporting prime is so long past, who went on living in the vicinity of the Strathfield branch of the Commonwealth Bank where he first worked on coming to the smoke. But if you were part of the cricket community, you also knew Davo as the guy who kept giving back, the epitome of the voluntary administrator and tireless enthusiast.

Davidson was still the patron of Cricket New South Wales, where he was president for thirty-three years without ever accepting a penny, his diary always virtually blacked out with cricket functions, where he may have eaten more rubber chicken than any Australian of his generation. How many glad hands of slightly starstruck followers did he shake down the decades?

Youth cricket was his great passion: the shield bearing his name, which involves 400 schools across New South Wales, lays claim to being the largest competition of its kind in the world. The first steps of a career, he thought, were always formative. Davo could recite from memory a letter his old headmaster sent in 1949 on the event of his selection was for the NSW second XI, wishing him ‘an honourable and successful career in the best of all games’.

‘I feel sure you have enough balance in your make-up not to allow success to go to your head and turn you into that most hateful of beings – a sporting snob,’ said the headmaster. ‘He who bears his honours with modesty, and behaves himself as a good sportsman should, is the one whom we admire.

‘Play the game, Alan, in the best traditions of sportsmanship.’ And he did.