The Last Dance shows flawed glory of Michael Jordan

A gripping series featuring Michael Jordan, which is set for its finale, delivers pain and glory to a competition-starved sports fans.

“When people see this, they’re going to say, ‘Well, he wasn’t really a nice guy. He may have been a tyrant’. Well, that’s you. Because you never won anything. I wanted to win.”

— Michael Jordan, The Last Dance

-

In the bars, cafes, restaurants and press boxes, I heard the same thing: this was Michael Jordan and the Bulls all over again.

It was 2015, and the Cleveland Cavaliers were hosting the Golden State Warriors in the 2015 NBA finals. I had been in the Caribbean covering Australia’s cricket tour of the West Indies. When the test finished early I begged the office to let me go to Cleveland and after a couple of plane trips, I landed at dusk and grabbed a taxi to the hotel on West Mall Drive.

The city was a towering landscape beneath grey skies. I thought of Gotham City. Plastered across one large building was a colossal image of LeBron James that reminded you of Christ the Redeemer, the statue above the streets of Rio de Janeiro. His arms were outstretched, his shoulders impossibly broad, the physique of a 208cm superhero. The message was clear. Upon those shoulders was being carried an entire town. On the back of his singlet instead of his surname, it said “Cleveland”.

That moment in Ohio gave me the strongest sense of how an American city grew wings from the exploits of an athlete like James, and Jordan before him. They aren’t part of the city. They are the city. On game night, when tip-off triggered a thunderous, wall-shaking, roof-raising din, I thought if this was history repeating itself … what a thing it would have been to witness the original 23. To have been in downtown Chicago when Jordan and the Bulls held their city, and their nation, and the entire sporting universe, in thrall.

Flash forward to April 19 this year. Sport has hit the skids. Pulled up stumps. There is no bare-knuckled NRL. No aerial ping pong. No soccer. No rah-rahs. No American sports: no Cavs, no Bulls. No Premier League. No Roger Federer, Tiger Woods, Serena Williams.

No hometown hype: No Ash Barty, no Steve Smith, no Dusty Martin. There’s a bit of horse racing at Royal Randwick and Caulfield, empty seats where there used to be emptier pockets, but the pandemic has done what neither fire nor flood nor war had previously — ground the sporting world to a total halt and we the sporting public are starved of the intrigue, the creation of legends, the heartbreak and brutality of professional sport.

But not completely. The Last Dance documentary arrives to a sports-starved planet. NBA superstar Dwyane Wade sums up the reaction: if he could’ve had three wishes before he died, one of them would have been the creation of this documentary.

Reportedly moved up from June after US sports channel ESPN found a pandemic-induced hole in its programming, the audience was there to be had and, oh, it’s been had. A hundred million viewers. A billion tweets. A trillion likes. On Monday night, the final episodes air in Australia. It has been compelling viewing from the opening scene: Jordan, the untouchable and mostly reclusive sports star, seated in luxury in a palatial home. Camera at his back. Head bowed. A waft of cigar smoke. Moody and contemplative.

Take Shane Warne and the Australian cricket team, and magnify their status by a thousand, and you might come close to the elevated worldwide station of Jordan and the Bulls in the 1990s.

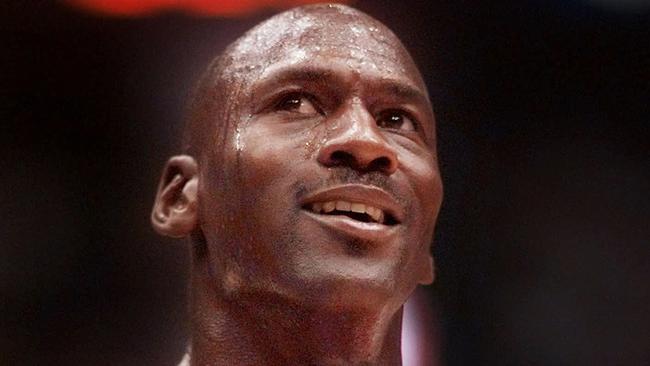

They were Chicago. A young Barack Obama clamoured for tickets. Bullsmania was the athletic equivalent of Beatlemania. Bedlam. Here is their story, told primarily by Jordan, now 57 years of age, yellow-eyed, a bit more fat-faced, still larger than life, open, honest, human — what an affliction — the cigar on the table and a good, stiff drink at his hand.

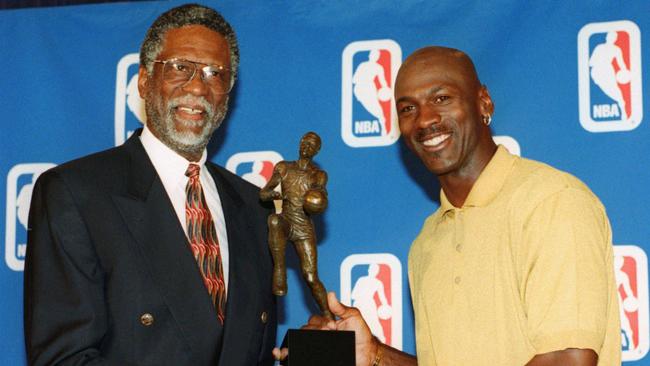

Great athlete. Complete prick. That was always the rap on Jordan. His Bulls won a hat-trick of NBA championships from 1991 to 1993. He retired when he was the biggest name in American sport and one of the biggest names in American pop culture, when he was one of the most recognisable humans on the planet. Introducing him on her show, Oprah Winfrey hollered: “The most famous man on the planet is here!” He was outed as a chronic gambler. His best mate, his father, the person he held most dear, was murdered. All a mess. “Adversity’s sweet milk,” Shakespeare might say. He played baseball. He quit baseball. He returned to the Bulls. What happened next is the focus of The Last Dance, which centres on the 1997-98 season, Jordan’s last at Chicago, when he had never played greater and he had never been more of a monster.

Jordan was, and — after watching this documentary few would dispute — remains, history’s greatest American sportsman. List the best athletes of all time and there you have it: Ali, Pele, Jordan, Federer, Woods, Bolt. But Jordan belittled, berated and humiliated his peers in his desperation to make them as good as him. He wanted them to be as committed as him. He believed he could pour glory on downtrodden, recession-hit Chicago in the 1990s — unless his teammates stuffed it up. He wanted to prove himself to be the greatest basketballer who ever lived, and perhaps the greatest athlete of all time — if only his teammates would let him. He was an individual athlete in a team environment. In control. Out of control. An obsessive, win-at-all-costs, trash-talking, grudge-holding, chest-thumping figure who called his teammates “bitches” when they failed to pull their weight.

He mocked and embarrassed them. Pushed them around. Always, he thought, to help them be better.

Eight episodes in and The Last Dance has added to our understanding of the Jordan years, with linchpin coach Phil Jackson, Bulls co-captain and team father figure Bill Cartwright. It has filled some of the emotional void left by the suspension of live pro sport with its voyeuristic rawness.

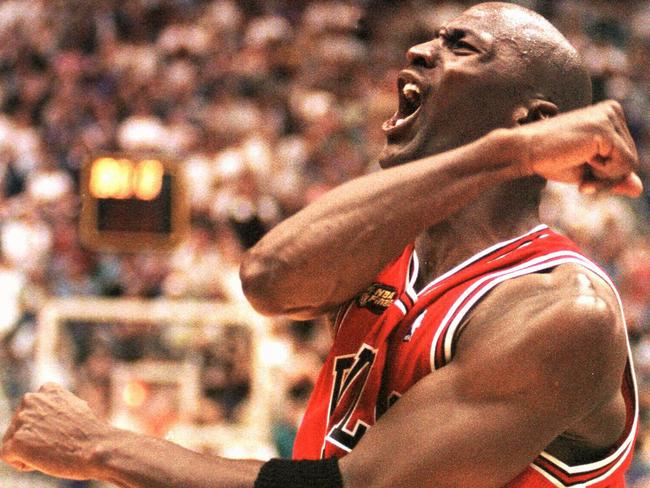

Did the sporting universe stop just so we could immerse ourselves in the story of Jordan and the Chicago Bulls? We can get into the Bulls’ locker room. Board the team bus with Jackson, the coach with the demeanour of a pot-smoking hippie. Walk out on to the court. Sit in on team meetings. One of Jordan’s wins was on Father’s Day, 1996. The footage of Jordan, all 198cm of him, the most impressive physical specimen you could imagine, howling in emotional agony while writhing on the dressing room floor, distraught that his old man was not there with him, is hard to shake. Previously unseen footage and interviews are courtside seats to the feuds, bitterness and explanations.

The Last Dance sends us back to the 1990s while 2020 is on hold. Back to shoulder pads and tucked-in T-shirts. There’s Letterman! Seinfeld! And the players. Scottie Pippen. Dennis Rodman. Magic Johnson. It’s been achingly nostalgic to be immersed in the past when the future is so uncertain.

Sport is full of unexpected twists. And when it looked as if we would be consigned to months of replays of league and AFL grand finals and replays of the replays on and on until sport returned, here was a welcome twist: Michael Jordan giving his own version of folkloric events; crying, laughing, commentating on every fight, every low and high when he touched the sky.

Air Jordan on the trappings of fame as a global brand, the psychological torments and mind games that drove him to bully and badger and harass the Bulls to want it as much as he did. When teammate Steve Kerr was annoying him, he punched his face. Kerr’s view now? It was the best thing that happened to him.

At one training session Jordan screamed at them: “Garbage! Don’t bring that bullshit! Shoot a layup, you dumbass! Go sit your asses down! Game time! Make this free throw, ho! That’s nine, bitch!”

His teammates are asked if it was worth enduring Jordan to win all those titles. They all give the same answer. Heck, yes. Says Will Perdue: “Let’s not get it wrong. He was an asshole. He was a jerk. He crossed the line numerous times. But as time goes on and you think back about what he was trying to accomplish, yeah, he was a hell of a teammate.”

What a shame it has to end.

In the most recent episode, Jordan becomes emotional talking about whether his absolute ruthlessness cost him respect. Those curiously yellow eyes (the subject of much internet speculation: is it jaundice? His liver?) well with tears. He says: “Winning has a price. And leadership has a price. So I pulled people along when they didn’t want to be pulled. I challenged people when they didn’t want to be challenged. And I earned that right because my teammates came after me.

“They didn’t endure all the things that I endured. Once you join the team, you live at a certain standard that I play the game, and I wasn’t going to take anything less. Now, if that means I have to go out there and get in your ass a little bit, then I did that. You ask all my teammates, the one thing about Michael Jordan was, he never asked me to do something that he didn’t f..kin’ do.”

He pauses as if he could not continue, and then he does: “When people see this, they’re going to say, ‘Well, he wasn’t really a nice guy. He may have been a tyrant’. Well, that’s you. Because you never won anything. I wanted to win, but I wanted them to win and be a part of that as well … That’s how I played the game.

“That was my mentality. If you don’t want to play that, don’t play that way.”

And then it is all too much for him and he says, “break”. He rises from his seat and walks away. But it’s not over yet.