Kimberley Indigenous issues need to be resolved first

Nearly half the population in the Kimberley is Aboriginal. Their wellbeing will ultimately reflect the wellbeing of the region.

It was just 18C on the morning Katlyn Yeeda apologised online to her followers for going quiet due to “the cold”. The Derby Jetty Queen – or Her Majesty, as fans across Australia call the fishing icon – had not posted a photo for a week.

“Sorry guys, haven’t been fishing lately, it’s been too cold for me. Yes, I’m a true Kimberley girl, I can’t handle the cold like every other deadly people can,” she wrote on June 29.

The 27-year-old Warrwa woman is the personification of living well in the warm Kimberley sunshine. Along the way, she is helping her followers understand more about her people and their lands.

Half of the Kimberley’s 35,000 residents are Aboriginal. The Indigenous population is diverse: there are 55 Indigenous languages spoken across the region covering 423,000sq km, an area almost twice the size of the state of Victoria or equivalent to the US state of California.

Yeeda asks her followers to use a fishing line, not nets, and to take their litter home. “Please respect country,” she says.

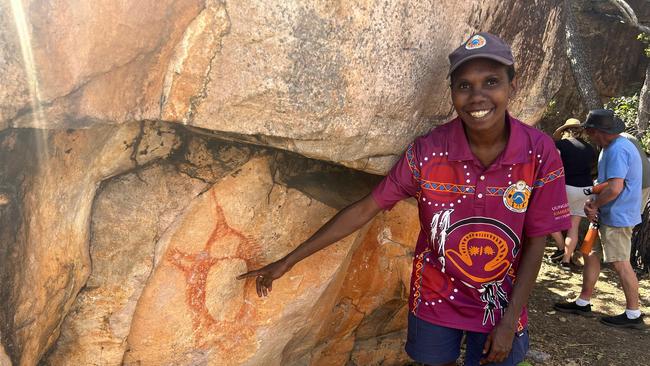

While Yeeda works at the Derby Visitors Centre by day, her most effective tourism work is clearly in her spare time, on her Derby Jetty Queen blog.

Her videos and stories from the horseshoe jetty in Derby, 2300km northeast of Perth, have become so popular that families from as far away as Melbourne plan holidays to the Kimberley because of her. Followers proudly share their selfies with the Derby Jetty Queen.

“Ha ha, yes, they tell me I’m a celebrity,” she says.

Yeeda does not need to exaggerate to make the Kimberley seem appealing to outsiders. Since records began, the temperature in Derby has never fallen below 6C. It is a town of striking imagery – it has 12m tides, boab-lined streets and bright orange sunsets.

However, she is candid about the difficulties beyond the lens.

For example, the Kimberley is grappling with a sustained wave of youth crime that has placed enormous pressure on frail elders to do what absent or impaired parents have not.

In December 2021, as the crisis ratcheted up, the region’s most successful publican Martin Peirson-Jones wrote to then-premier Mark McGowan likening the region to Port Moresby.

Car theft and police baiting had become a rite of passage for some children, he said.

“The intergenerational failure to properly educate children prevents them from gaining meaningful employment and contributing to society,” Peirson-Jones wrote.

Elder Ian Trust, from the town of Kununurra, called for a major crackdown on the sale of alcohol. Trust was a supporter of the cashless debit card and has publicly lamented that Labor did not consult his community before cancelling it.

Over the past three years, the debate over the poor health and economic status of Indigenous people in the Kimberley has variously focused on the scourge of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder, the potential merits of blanket alcohol restrictions and the promising results of small but effective crime prevention programs.

In and around the Kimberley town of Halls Creek, the Olabud Doogethu initiative sends Indigenous night officers into the streets to talk to children who are not at home.

It has resulted in a 58 per cent reduction in burglaries, 35 per cent reduction in stolen motor vehicles and 28 per cent reduction in stealing offences. Optimists see the very high unemployment rates among Indigenous people in the Kimberley as potential.

Tourism Western Australia is responding to a growing appetite for Indigenous experiences with the Camping with Custodians initiative. The first of these was the Imintji campground, 220km east of Derby on the Gibb River Rd.

Tourism WA promotes the camps as a way for non-Indigenous people to experience for themselves a remote Indigenous community.

“Visitors can stay on Aboriginal lands and meet and mix with Aboriginal people, with the fees they pay for their accommodation staying in the community,” Tourism WA says on its website.

Traditional owner groups in the Kimberley are making headway in business ventures because many are now landowners or have rights to their traditional lands that previous generations did not have.

The fact that Native Title has been recognised over more than 97 per cent of the Kimberley presents economic opportunities that did not exist 30 years ago.

The Kimberley Land Council recently highlighted the torment of past leaders when it republished the words of one of its founders, John Watson, from 1986.

“We watch TV, see the news, and have got no say. People all over the world are being forced to take what is given to them, we as Aborigines most of all, because so many people still refuse to recognise that this is our land, our heart, our country,” Watson said.

“We don’t want to take whitefeller’s backyards or farms. We just want enough land to live in dignity, where our children can grow up with self-respect. We have been undermined and put in corners too long.

“We have support from all over the world and cannot step away from the struggle. It is the land councils that carry our message out on to the streets of the world and tell of our situation.

“I have identity, I have feelings for our people. Land rights have been thrown out, but we still demand that self-management and self-determination be initiated in times to come.”

Two decades later, Watson was head of the Kimberley Land Council when it took a stand against green interests by supporting a proposed gas hub on the Kimberley coast.

The proposal was backed by a billion-dollar package of economic and social benefits for Aboriginal people over 30 years, including housing and jobs.

Woodside ultimately walked away from the proposal in 2013 amid national outrage over the economic toll of the project.

It was a bitter lesson for traditional owners, who had voted for the gas hub and believed they had control over what happened on their country.

However, Indigenous organisations in the Kimberley continue to eye economic opportunities. Some are also entering into partnerships with government to prevent crime. They see jobs, and long-term benefits in helping to design and implement programs that divert Indigenous children away from the courts.

Yeeda hopes that her son, Raphael, six, takes a different path from the one that troubled kids in Derby are on.

“He has a mum who is disciplined so hopefully that helps him,” she says.

“They just have their own ways now, the kids.”

Yeeda said she had been to “a lot” of town meetings about youth crime and realised people were asking the wrong questions.

“Everyone seems to be asking the elders or people like me: ‘What are the kids interested in?’,” she said.

“What they should be really doing is asking the kids. We can’t think for them.”

It was on a recent drive to her beloved Derby jetty that Yeeda heard from children’s own mouths what was troubling them.

“I saw them walking to jetty and I said, ‘You kids need a lift’ and they said yes and got in,” Yeeda said.

“They started talking and they said they were that bored in town. They had nothing to do.”