Take nuclear submarines deal at more than face value

By the time the “optimal pathway” for nuclear-powered submarines was revealed in San Diego last month, after 18 months of intense speculation, almost every detail had already leaked. Most observers assumed one or another of the plans would turn out to be correct; none guessed it would be all them.

When the trilateral AUKUS pact first broke the surface in September 2021, it was much like when an actual submarine unexpectedly does so: the shock and alarm could hardly have been greater.

But by the time the “optimal pathway” for nuclear-powered submarines was revealed in San Diego last month, after 18 months of intense speculation, almost every detail had already leaked: A rotational force of nuclear-powered submarines (SSNs) from the US and UK centred on Western Australia’s HMAS Stirling … The purchase of 3-5 of the US Navy’s Virginia-class boats … The co-design and co-build of an SSN AUKUS boat between Australia and the UK.

Most observers assumed one or another of these plans would turn out to be correct; none guessed it would be all of the above.

But the twist in the tale was the price. During the preceding 18 months, the most often quoted estimate from the Australian Strategic Policy Institute had been $171bn. In the days before the announcement, speculation began creeping up to towards $200bn. But then journalists were briefed that the actual cost range was $268 to $368bn, covering every aspect of the commitment until 2055. (In the short term, $9bn will be spent across the next four years, offset by $6bn budgeted but not spent on the now-abandoned French Attack-class submarines and further $3bn in savings to be detailed in the Defence Strategic Review this month. And over the next decade, $58bn will be spent, offset by $24bn not spent on French boats.)

So, the eye-catching plan comes with an eye-watering price. Suffice it to say, a forecast decades hence including assumptions about inflation, foreign exchange rates, and countless other design variables, is certain to be inaccurate. But as Warren Buffett is fond of saying “price is what you pay, value is what you get”. How do we value such a deal?

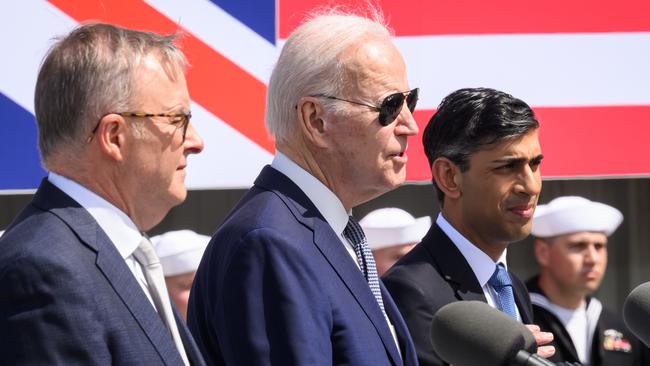

The case made by the three leaders seemed more about industry policy than defence. Nobody uttered the word “Taiwan”, but they certainly emphasised jobs, technology spillovers and economic benefits. US President Joe Biden noted “an awful lot of good-paying jobs for all workers in our countries … a lot of union jobs.”

UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak hailed “thousands of good, well-paid jobs in places like Barrow and Derby”. Prime Minister Anthony Albanese described the deal as “the biggest single investment in Australia’s defence capability in all of our history” adding “this investment will be a catalyst for innovation and research breakthroughs that will reverberate right throughout the Australian economy and across every state and territory, not just in one design element, not just in one field, but right across our advanced manufacturing and technology sectors, creating jobs and growing businesses …”

In Australia’s case, the immediate investments and jobs will centre on the submarine base at HMAS Stirling on Garden Island near Perth, and on the Submarine Construction Yard at Osborne in South Australia. (The expected announcement of a new east coast base at Port Kembla has not materialised, perhaps given the proximity to the recent NSW election.)

Defence has revealed that HMAS Stirling will receive $8bn investment across the next decade, for purposes including wharf upgrades; facilities for operational maintenance, logistics and training; and other off base supporting infrastructure. It claims 3000 direct jobs will be created, plus 500 direct jobs to sustain the US and UK rotational forces.

In the forward estimates, Defence expects to spend $2bn in Adelaide. It claims the creation of 4000 direct jobs to build the Submarine Construction Yard, and a further 4000-5500 direct jobs to build the submarines themselves.

During the 30-year time frame, the creation of 20,000 direct jobs across industry, government and defence are predicted, though they should be treated with the same caution as long-term estimates of cost. It must also be said, with Australia’s current unemployment rate of just 3.5 per cent, this is not addressing a jobs crisis.

But what of economic spillovers? The experience in the past decade with Naval Group and the aborted Attack-class submarine is eerily similar and should give us pause. It began with near identical claims from then-prime minister Malcolm Turnbull in 2016, that the project would “secure our successful transition to the economy of the 21st century” with “immense spin-offs into the rest of the economy”.

During the design phase, orders for four of the five major subsystems were placed with European providers, and controversy about local industry participation erupted. Naval Group eventually committed to spend 60 per cent of the contract value locally and disclosed a list of 137 current domestic subcontractors which included local subsidiaries of foreign companies, a French language training provider, and recruitment firms, among others.

Experts at the time warned that the whole enterprise was less hi-tech than it seemed, noting that it was a 20th century-style industrial production, featuring mature technologies built on foreign intellectual property, with no realistic prospect of manufacturing for export and with defence secrecy necessarily curtailing spillovers of innovation.

“(Spillovers) are all about hi-tech industry, where you can play on our domestic strengths in university research, generate intellectual property, and then produce products and services you can sell to the world,” analyst Marcus Hellyer says.

An R&D subsidiary – Naval Group Pacific – was formed to jump-start local investment but was hamstrung by Covid. By the time the contract was cancelled in 2021 – admittedly before construction had begun – there was little to show in terms of economic renaissance.

Recently, economist and Lowy Institute senior fellow John Edwards asked pointedly “if the past two generations of submarine building projects in Adelaide did not create a major flourishing industry which outlasted the submarine projects, why should this one?” In a recent article for The Interpreter, he also questioned whether the analogy of the Australian car industry created after WWII was helpful, given that it was eventually shuttered due to a lack of exports, competitiveness, and scale.

A … straightforward argument for the SSN project’s value could be made in terms of military capability and defence strategy

“Nuclear propulsion is after all now a very old technology,” he writes, and “Australia will anyway only acquire bits of the technology. The nuclear reactors will be made elsewhere, the weapons, communications and control systems made elsewhere, and the vessels designed elsewhere. The submarine project is a cut above a flatpack assembly business, though perhaps not all that much above.”

Perhaps the greatest prospect for economic spillovers is in the part of AUKUS we have heard the least about: Pillar Two advanced defence technology co-operation.

A more straightforward argument for the SSN project’s value could be made in terms of military capability and defence strategy.

Thus far, it can only be gleaned through a mosaic of comments and educated suppositions. SSNs have been described by our defence officials in vague terms such as the “apex predator of the ocean” and “the equivalent of a Queen in a game of chess”.

It is well known that nuclear submarines are stealthier in not needing to periodically “snort” oxygen near the surface like diesel-electric boats; they are faster and can stay on-station longer; in addition to anti-ship and anti-submarine torpedoes, they will carry Tomahawk Land Attack Missiles (as will the upgraded Collins-class submarines); and their size will make them the motherships for launching of, and teaming with, the unmanned autonomous vehicles of the future.

But by and large, submarine operations are shrouded in mystery. Aside from occasional port visits and publicised exercises with allies, and the presumed intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance missions, we have little notion of what they are doing.

Defence officials privately say the more they detail about the uses of submarines, the less value they will have, since adversaries are always listening. Conversely, intelligence agencies across Australia, the US and UK have made considerable efforts in recent years to increase transparency with speeches, interviews and flashy websites, which describe what they do without compromising their methods, in order to preserve their “social license”.

Further, if SSNs are the “ways” and the price is the “means”, then the strategic “ends” are also left unclear for political and diplomatic reasons.

Biden referred to the “one overriding objective: to enhance stability in the Indo-Pacific amid rapidly shifting global dynamics.” Deterrence was mentioned by the leaders several times. Sunak was the only leader to mention China by name.

Australian Defence Minister Richard Marles has since been forced to clarify that no commitment was asked for or given to the US in relation to Australian SSNs potentially defending Taiwan from a Chinese invasion.

Whether SSNs precipitate an economic transformation or not will be a debate for economists and historians many decades hence. But the immediate task of explaining the SSN’s value remains and is only going to get harder when the Defence Strategic Review is launched this month, possibly revealing the defence capabilities we have to forgo, followed shortly thereafter by the Budget in May where every other unmet societal need will be brought into focus.

Before support for AUKUS declines – or a false alternative of “guns vs butter” becomes anchored in taxpayers’ minds – the opportunity exists to establish a different narrative.

It should be one that reveals just a little more about our submariners: the men and women who have underwritten all our jobs, prosperity and security for decades, and the awesome new capabilities they need to continue this work in increasingly dangerous times.

-

Justin Burke is the Thawley Scholar at the Lowy Institute and Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington.