Stemming the tide of gender bias

Women are powering ahead in fields that have traditionally been dominated by men.

Ashlee Caddell first began enjoying science when she was 10 years old.

Now 28 and a University of Queensland astrophysics doctoral candidate researching dark matter, she has had a long struggle with gender stereotypes – from being one of just a few girls in a Sunshine Coast state high school physics class, to coping with mean schoolboys digging at her for enrolling in “a boys’ science”, to facing undermining comments from the people around her as she matured and stayed with science.

“I remember when I was applying to university, for some reason my hairdresser thought it was important to tell me that women are bad at maths and that I shouldn’t do physics because I would just fail terribly at it,” she says. “It was a very strange thing for her to say to me.”

Ignoring her hairdresser, Caddell is now one of the young Australian women who have successfully embraced science, technology, engineering and maths – the fields still predominantly associated with men, and predominantly chosen by boys at school and young men entering university.

Experts fear that according to current enrolment trends, Australia will not be able to supply enough STEM graduates – particularly engineering and IT graduates in coming years – and a lot of that shortfall is due to young women choosing not to study STEM.

In 2022, according to the federal department of Industry, Sciences and Resources’ STEM Equity Monitor, women comprised 37 per cent of STEM university enrolments, clustered in agriculture, environmental and related studies, and natural and physical sciences. Women made up 20 per cent of engineering and related technologies enrolments and 22 per cent of information technology enrolments.

“We are still gendered in most careers even for STEM,” Australia’s former chief scientist, Cathy Foley, said in February on winning an Australian Award for Excellence in Women’s Leadership.

“While we have lots of girls and women doing the life sciences, they have insecure work and don’t get promoted. In the physical sciences we have a pipeline issue where girls don’t choose high level maths and physical sciences and so there are few women. Even after decades of effort and initiatives, we are not there yet. There is still work to do.”

Caddell, who recently co-led a study on a different way to look for dark matter using atomic clocks and cavity-stabilised lasers, says enthusiastic early science and maths teaching is an important part of encouraging little girls’ interest in STEM.

“My teachers in primary school were very good at engaging us, and they did little demo experiments fairly frequently,” she remembers. “They made it fun, and so it made me super-interested in everything science had to offer.”

A primary school teacher recognised Caddell’s maths ability and took pains to encourage her interest, assigning her special extra homework that she could do in her own time, and at her own pace, to hone her maths skills. “Without her, I don’t think I would be interested in maths or science at all, to be honest, she was truly a very amazing teacher,” Caddell says.

Later on, in high school, she enjoyed completing a project on star formation which set her on the road to study astrophysics at university. Along the way, she ignored the sexist questions from people asking her why she, as a girl, wanted to study physics.

“I guess it could be interpreted as concern, but it was just very undermining,” she says.

“I think part of me is still in this field out of spite, just to show everyone who doubted me that, yes, I can actually do this.”

A dedicated maths teacher in Caddell’s last years in high school again fired her enthusiasm for the subject. “She made me realise that maths is really quite beautiful,” she says. “She was so just endlessly encouraging and so passionate that I genuinely don’t think I could have done it without her.”

Girls were in the minority in the advanced maths stream when Louise Campbell, usually called Lou, was enrolled at co-educational Xavier College in Gawler, South Australia, in the ’90s, and there was little encouragement for her to pursue her interest in pure mathematics.

“It started when I was in high school,” she says. “I loved maths and science but I think, back then, we had to choose a career, as opposed to just following what you enjoy.”

Finishing high school in 2001, she enrolled a Bachelor of Finance course, which she didn’t like and she soon dropped out. After a business college course to refresh her computing skills, she began work with a financial planning company where she stayed for 10 years.

Then Campbell’s life changed, she had a baby, split with her partner and moved back to Adelaide as a single mother. Maths again attracted her, and she enrolled in Bachelor of Teaching and Bachelor of Mathematics courses at the University of Adelaide.

“I just felt like, after I had my child, I had the confidence to pursue something I was passionate about, and not what others thought I should do,” Campbell says. “After a while, though, I dropped the teaching stream because I just loved the maths.”

Now 41, she says she was “hugely outnumbered” by men, both students and academics, in the department. She eventually graduated with honours degrees in maths and computer science in 2019, and she is now at work on the research for a doctorate in statistics, also at the University of Adelaide, as well as teaching a first-year statistics course.

“I’m very passionate about it,” she says. “I really love being seen as a woman lecturer in mathematics, and I want to be a role model for other women and young girls.”

Campbell began her doctorate in 2020, but she’s been interrupted by the Covid pandemic and hopes to finish the research and graduate at the end of next year.

Her research project combines two of her great interests, mathematics and forensic science.

“I am looking at building a system, something like a recommender system that will assist the decision-makers of forensic science to choose which exhibits to test for DNA,” she says, referring to pieces of evidence that might be used to detect crime and prosecute criminals.

Netflix and similar streaming organisations use recommender systems that are designed to recommend films to clients based on analysis of the client’s own film choices. Various details might come under consideration, including how receptive the item is to retaining DNA, exactly where the item was found in relation to the crime, the level of the crime, how many suspects there are. Campbell’s system will use immense troves of data, different aspects of data science, and different types of artificial intelligence to come up with a short list of recommendations for DNA testing.

She’s not entirely sure how the final system will operate, but she says if there are 20 potential pieces of evidence, it might recommend the five with the most potential, and the decision-maker might choose two of the five.

Once she has the statistics doctorate under her belt, Campbell says she might strike out into the private sector, or she might remain in academia.

“I do love teaching,” she says. “I do enjoy being here. I enjoy my research. I love that I can combine something that I love, like statistics, with another field of interest, like forensic science.”

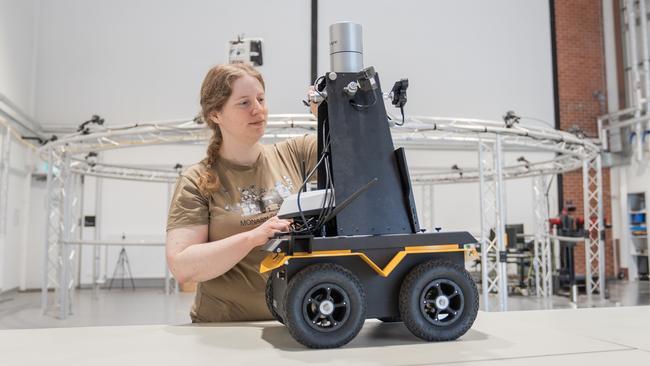

For her part, Aimee Allen is investigating human-robot interaction, specifically the sounds robots could make or should make around humans.

Now 38 and studying at Monash University, Allen expects to finish her doctoral thesis in August. She says she hasn’t experienced too much gender bias in her years at school or university, or now at her part-time job at an engineering firm, although most of her current lab colleagues are men.

Allen went to the Anglican all-girls Meriden School in Sydney which was largely free of sexist bias, graduating in 2003 and then heading straight to the University of Sydney, where she planned to take double degrees in commerce and engineering/mechatronics (the combination of mechanics and electronics).

“They told me I was mad and that was a stupid combination,” she says. “And I said, ‘why is it stupid?’ I want to build stuff and understand how to sell the things I build’.”

She fell off a horse and broke her back and while she was recovering she decided she would leave the university with just one degree, a Bachelor of Commerce. She graduated in 2009.

Allen then worked in administration, before moving to professional development, and creating mostly finance and STEM courses for a training company. She finally decided there was only so far she could go with an undergraduate commerce degree and she wanted to move into hardware.

“I want to do robotics,” she says. “I want something that exists in reality. I want to do the hard hardware.”

She expects to finish her thesis this year and when she graduates she hopes to keep working, probably for the engineering firm where she currently has a part-time job.

She and her colleagues are making mechatronic multi-modal devices to improve the safety of road workers.

Although Allen believes Monash University is pro-women in many areas, she says overall women studying STEM have struggled and were underestimated for far too long. “Obviously we’ve got several decades to catch up on from when places weren’t equal.”