Sovereign Defence satellite capability difficult to achieve

Developing a sovereign satellite capability in a domain as complex as space was always going to be difficult – and Defence project JP 9102 will only get us halfway there.

Developing a sovereign satellite capability in a domain as complex as space was always going to be difficult – and Defence project JP 9102 will only get us halfway there.

With an undisclosed budget believed to be in the $6-8bn range, it will provide Australia with a secure military communications satellite network covering the entire Indo-Pacific region. The system will also be used by other government agencies needing highly secure services, such as Foreign Affairs and Trade.

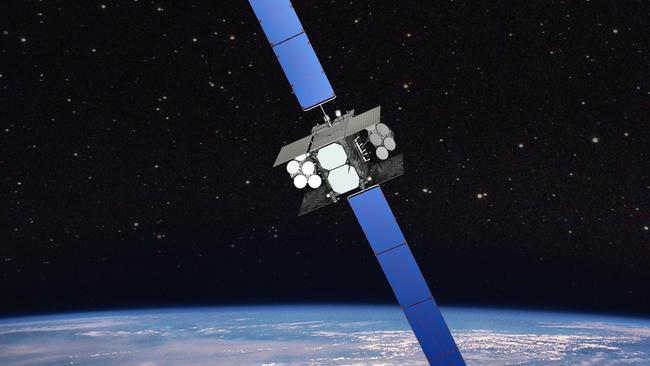

The way that the tender has been structured means that the network must be made up of our quite large satellites in geosynchronous orbit about 37,000km above the earth. As each of these will have an indicative weight of 6 tonnes, to reach such a distance from earth – and for the early part of the journey fighting gravity – they will need a heavy launch vehicle to get them there.

Typically, these types of satellites are launched in pairs to reduce the risk of the entire network being destroyed in an accident during – or soon after – blast off.

As technology advances, these sorts of mishaps are becoming more rare – like airline disasters – but they do still occur. But launches are expensive – especially when insurance is factored in – and if Australia’s satellites went up one at a time it would add significantly to cost.

The problem is that Australia does not have the capacity to build large satellites of this kind, nor do we have the huge rockets available to launch them into geosynchronous orbit. We will be dependent on overseas suppliers for both of these functions, which somewhat lessens the claim that these Defence satellites are somehow a sovereign capability.

Parts of the network will be, but overseas suppliers will dominate the critical elements of the project.

There are five competing prime contractors, all with a network of Australian industry partners: Airbus from Europe and then Boeing; Lockheed Martin; Northrop Grumman; and Raytheon – all from the US via their local subsidiaries. Some are not disclosing their launch partner for commercial reasons, but Arianespace with their facility in French Guiana in South America is a favourite.

Other contenders could be Elon Musk’s SpaceX Heavy – and in the case of the Raytheon bid one of their partners is Japan’s Mitsubishi, which builds satellites and large capacity rockets.

If Defence had chosen a different solution involving a low-earth orbiting constellation of small- and medium-sized satellites, the opportunities for Australian industry would have been greater because these technologies are well within our grasp.

And not only are large satellites beyond current capabilities, but the way that the project is structured, the prime contractor also has to cover the massive commercial risks of the project and no local space technology company is anywhere near large enough to carry that burden.

Thankfully other important elements of JP 9102 will feature very high levels of Australian content. These are principally the ground segments – the huge dishes and control stations that operate the satellites – and the management of the network for its 30-year life.

It is also possible that some satellite hardware could be sourced from Australia, but the existing manufacturers already have well established supply chains.

Because of Australia’s size, ground stations are usually needed on both the east and west coast – for example to handle our access to the current US Wideband Global Satcom military network.

These are very complex pieces of secure engineering, often costing hundreds of millions of dollars.

Similarly, operating and controlling satellite constellations – even with high levels of automation – is an expensive business and at least that money will remain in Australia.

The satellite network, which does not look particularly sovereign, is set to be in orbit and operating by the end of the 2020s.

As is often the case for Defence projects, if planning and work had started earlier, then Australian content would be greater. What often happens is that the required in-service date is so close – relatively speaking – that only mature, overseas solutions can meet the timeline once a winner is selected.