Drones, AI weapons ‘third revolution in warfare’

Artificial intelligence can control increasingly sophisticated uncrewed aircraft and submersibles, changing the nature of warfare.

Artificial intelligence can control increasingly sophisticated uncrewed aircraft and submersibles, changing the nature of warfare and raising questions about the many millions of dollars Australia is now spending on buying and developing crewed aircraft and submarines.

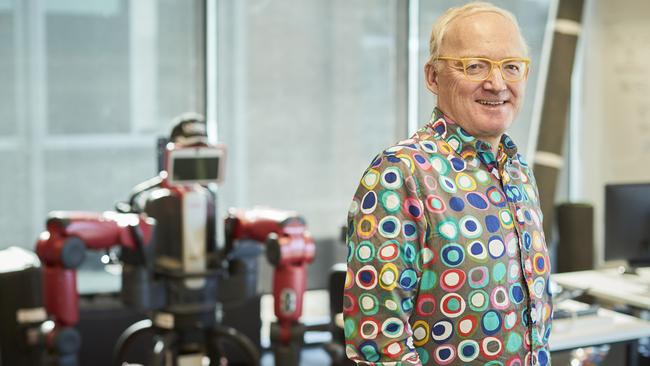

Dominant on the frontlines in Ukraine, large-scale swarms of AI drones can overwhelm almost any opponent, says University of NSW Scientia professor of artificial intelligence Toby Walsh.

For its part, Australia, (and Boeing) with AUKUS partners, is developing the MQ-28 Ghost Bat drone, but at the same time the Australian Defence Force (ADF) is sinking a lot of money into the F35 fighter jet, crewed by human pilots. Walsh adds that the jet is a “a very expensive piece of kit”.

He sees drones and other uncrewed aircraft overtaking jet fighters in the years to come, citing size, cost and manoeuvrability.

“If you see a swarm of drones, you know AI is flying them; humans don’t have the capability to pilot multiple vehicles at the same time,” Walsh says.

The US air force, he adds, now has more drone pilots than it does pilots of any other type of aeroplane.

A drone’s weakest point is the radio link, which allows identification of the pilot and destruction of the drone itself. Autonomous drones are not reliant on radio links, Walsh says, which makes them a “much more capable, much more potent weapon”, and provides a distinct military advantage.

Warfare, without humans in the mix, can be scaled up, and humans can be pulled back from the frontlines. But once humans are removed from the decision-making loop, Walsh says, war is in new legal, moral and ethical territory.

Dr Paul Robards, Defence’s chief data integration officer, says that while there are lessons to be learned from the Ukraine conflict, it should be recognised that future conflicts might be different in nature.

“So we need to have the balanced, integrated force able to respond to the sorts of situations that are outlined in the national defence strategy,” he says.

At the same time, he adds, there’s a continual defence forces push to get ahead of the opposition in conflicts by developing countermeasures and strategies.

“What we see through the history of warfare is as a system is developed, then someone will develop a counter to that,” Robards adds.

Robards is in charge of the Defence AI Centre, part of Defence’s data division. Established last year, the centre now has about 12 operatives and it functions on a hub-and-spoke model, he says, to enable and co-ordinate the department’s AI projects and activities.

AI can leverage machine learning, robotics, natural language processing and computer vision to boost efficiency, effective decision-making and strategic advantages.

“We’re developing policies within Department of Defence around the use of that (AI weapons), and this will come down to how we manage the risks and ensure that we have humans involved where they need to be, particularly for those higher-risk sort of activities,” Robards says.

AI that gives systems a level of autonomy enables the ADF to send more “mass to the battlespace” without having to risk human life, he adds. “AI and autonomy provide opportunities too, for us to remove humans from levels of risk in some of these activities.”

Walsh says AI will transform warfare and great care is necessary – particularly with the delegation of decisions to AI. “It’s been called the third revolution in warfare, the first was gunpowder, the second nuclear weapons,” he says.

“It’s a step change in the way we can go about fighting war. We should think carefully about exactly how and where we let that happen, and where we should think about trying to come to some global consensus, just as we have around cluster munitions or anti-personnel mines and various other things.”

AI autonomous weapons have the potential to spiral conflicts into ever more dangerous territory, Walsh adds. “When it’s AI systems facing off against each other on the DMZ between North Korea and South Korea, you might have started a great conflict, you can’t unkill all the people you’ve killed. It might escalate at that point to a nuclear conflict.”

On the safer end of the scale, the Australian Defence Force sees potential in AI-powered sentinel systems that at their simplest can detect movement, determine what is moving, and send alerts back to base, Robards says.

He adds that the military operates an array of surveillance and reconnaissance assets, including equipment such as sonar buoys, which are dropped into the ocean and then collect massive troves of data that can be processed and analysed by AI, often with levels of detection beyond human capability.

“They will give our people the ability to make better-informed decisions and to operate in that decision cycle faster than adversaries can,” Robards says. “So that’s a huge source of advantage for any military.”